[

] 200

Farmers’ organizations in a fruit-producing

region of Armenia

For centuries, Armenia’s Meghri region has been famous for

producing high quality persimmons, pomegranates and figs. The

region’s sub-tropical climate is perfect for growing, and consumer

demand for these fruits is high. But the collapse of the Soviet Union

and a lack of investment in agriculture has meant that many local

farmers have been unable to maximize their potential.

A key challenge for farmers has been the difficulty of accessing

agricultural supplies such as fertilizers and pesticides. Most have

to be purchased in Yerevan, and the small size of Meghri’s farms

means that farmers have little bargaining power, and often have

to pay high prices for supplies. Being aware of this challenge, SDC

encouraged farmers to get together to bulk-buy supplies. After only

a few years this measure has led to a reduction of about 20 per

cent in the price paid at farm level.

The same farmers’ organizations were also instrumental in selling

the fruits: wholesalers and supermarket chains are much more

willing to buy in bulk than to bargain with individual farmers for

small amounts of produce. In this way the farmers’ organizations

opened new markets to Meghri’s small family farms. Even better,

the fact that there is a functioning market for fruits attracted new

investments to the region. A local fruit processing plant now plans

to expand for producing a new variety of fruit juice, and this will

increase the possibilities for famers to sell their produce.

In the future it is envisaged that input suppliers will set up shops

in the region so that farmers can buy directly from them. A good

indicator that this could be successful was a two-day agricultural

fair organized with the help of the project in Meghri town. It was

attended by 250 farmers and 10 wholesalers of agricultural

supplies. Five wholesalers sold their products at the fair, and the

interest of the farmers and the level of sales were far higher than

the suppliers had expected.

overcome these challenges and to lobby for policies, regula-

tions and investments to realize the potential of family farms.

Access to services and markets

The most frequent reason for farmers to get organized is to

jointly market or process a common product such as milk,

fruits or grains and to access inputs as well as information

and financial services for its production. Due to the small

size of most family farms in Africa and Asia they face higher

transaction costs and lack negotiating power. Considering all

farms worldwide, 73 per cent are of less than one hectare

and 95 per cent cultivate less than 5 hectares of land. But the

estimated 500 million family farms located in Africa and Asia

are sustaining the livelihoods of about 2 billion people and

providing food to at least half the world’s population.

On the input side, service-providing farmers’ organiza-

tions bulk-purchase agricultural inputs and resell them to

members at a favourable price. On the output side they bulk-

produce and benefit from lower transaction costs and higher

bargaining power in sales. Farmers’ organizations also play

an important role in the provision of information to family

farms. As a group it is easier to access information on new

production technologies, new crop varieties or approaches for

sustainable natural resources management.

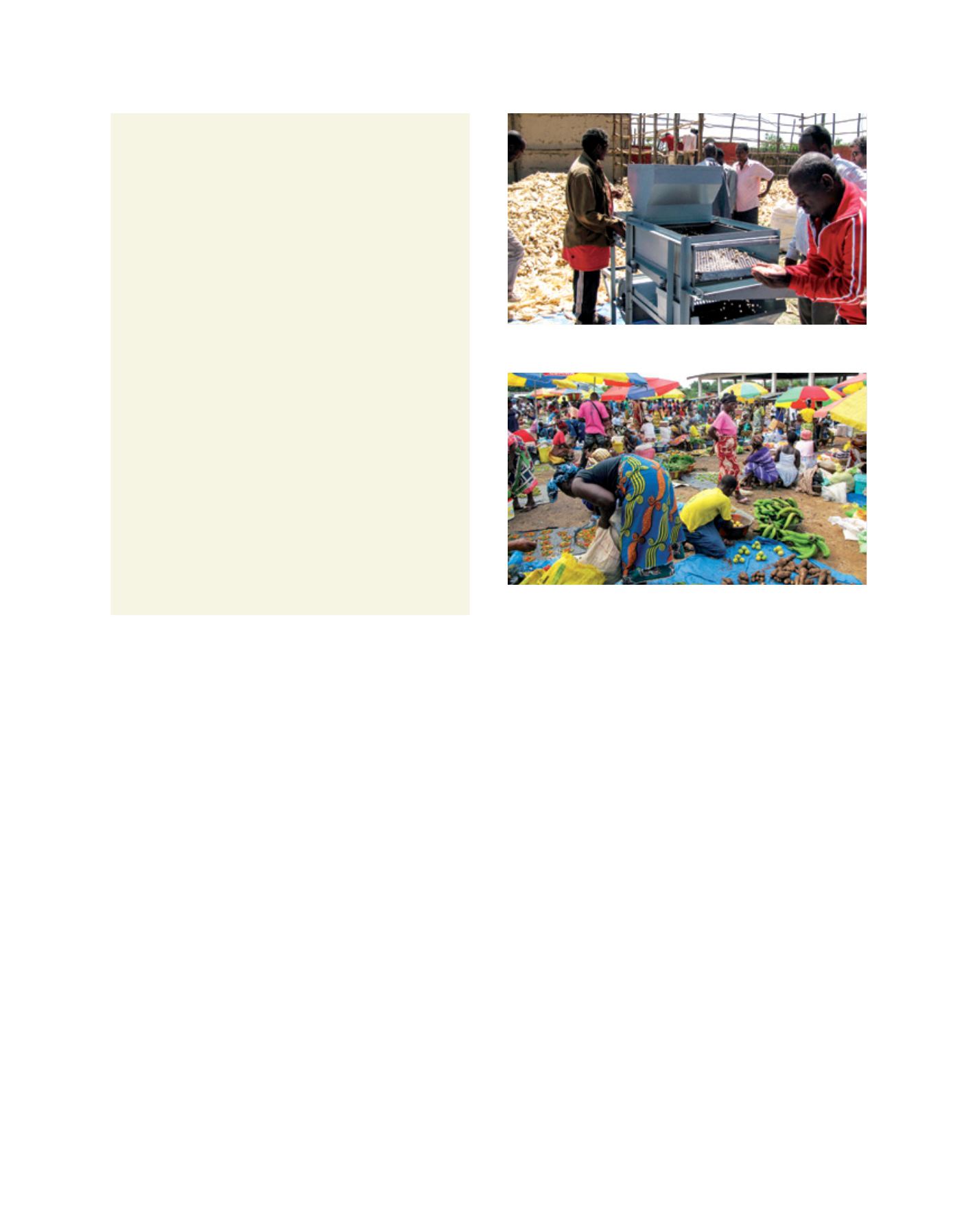

In production, family farms still rely heavily on manual

labour. While locally adapted mechanization would be available

on the market, this is not affordable for individual small enti-

ties. Labour in rural areas is often scarce due to increased rural

urban migration, a lack of interest among youth in farming and,

in some regions, a diminished workforce due to early death

caused by conditions such as HIV-AIDS. In a post-harvest

management programme in Ethiopia for example, it was a local

farmers’ organization that enabled the farmers to buy modern

threshing equipment that makes threshing easier while also

reducing losses of maize due to spilling and damaging grains.

Sustainable use of natural resources

Farmers’ organizations are essential for the definition of regula-

tions for the sustainable use of natural resources. Family farms

in many cases use common natural resources such as pasture

land, forests, lakes or rivers and often lack legally recognized

and secured access to these resources, which form the basis for

their production and livelihoods. Unsecured access to natural

resources discourages investments whose benefits – for example

trees or works to halt erosion – only occur several years after

the investment. Furthermore, unsecured land tenure rights

inhibit the use of land rights as collateral for credit. In areas

with increasing population pressure, unsecured tenure rights

also lead to the overuse of the resource and to conflict in society.

Farmers’ organizations can play a regulative role and act as

the first level in conflict mitigation. In Mongolia for example,

Switzerland is supporting pasture user groups to sustainably

manage state-owned and free-to-use pasture land. In this de

facto open access situation where each herder tries to maxi-

mize his or her animal production, the natural resource base is

put under heavy pressure and is strongly overused, particularly

Local farmers’ organizations can enable farmers to buy modern, labour-

saving equipment that reduces losses through spillage and damage to crops

By bulk-selling produce, farmers’ organizations can open up new markets

to small family farms

Image: Markus Buerli, SDC

Image: Séverine Weber, SDC

D

eep

R

oots