[

] 55

establish a secure and sustainable future for family farming in

the context of global food security.

The importance of young farmers to family farming is fairly

self-explanatory, considering farming businesses and the land

they are on are passed from generation to generation – there-

fore, a new generation of farmers will always be necessary

to continue the trend. However, it is important to note that

farming, compared to other businesses, tends to stay in the

hands of the older generation for much longer. This is often

quite surprising considering the comparatively increased level

of physical labour necessary, but it can perhaps be explained

by the years it takes for someone to perfect their farming skills,

as farmers can only really learn from their mistakes once per

harvest, compared to other careers where learning curves may

happen much more frequently. It is also likely to do with a

connection to the land, animals and production in general – a

farmer works in harmony with nature in order to reap its bene-

fits while ensuring it can continue to provide him and future

generations with income in the future. Global statistics are hard

to come by in the field of agriculture but, for example, in the

European Union (EU), the average age of a farmer (defined as

the head of the holding) is 55. This is problematic in the context

of food security for a number of reasons, primarily because of

the missed opportunities in terms of increased productivity,

efficiency and sustainability of family farms.

In the EU, young farmers are defined as heads of holding

under the age of 40. Although these make up just 7 per cent

of the farms in the EU today, it is these in particular which

consistently produce more food per hectare than their older

counterparts. It is difficult to say exactly why this is the case

with any certainty, but easy to come up with a few ideas. Higher

young farmer productivity is likely to be down to a number of

factors, including a higher level of education than their prede-

cessors – with many young farmers in the EU now holding

highly-respected academic qualifications such as degrees in

agronomy, agricultural economics, business management,

environmental studies and more. Young people are also more

technologically able, leading to the use of innovative farming

techniques and modernization of the family farm to enhance

productivity while safeguarding sustainability and biodiversity,

in keeping with the traditions of a family farm and ensuring

its survival. Because of their increased productivity, established

young farmers are also more likely to employ more labour than

others. Finally, young farmers are more adaptable –more likely

to be willing to change produce, buyers or carry out activities

such as direct selling, bringing consumers closer to farmers

while ensuring a decent price for both parties. All these factors

contribute to a clear picture: a younger farming population is a

more productive one, and therefore more likely to achieve global

food security. But in a world with an ageing population, particu-

larly in the farming sector, what is to be done to achieve this?

Although family farms still make up the majority of food-

producing farms across the world, they are in decline, and have

been for some years. This has been caused by the lack of interest

shown by many young people in taking over their parents’ farm.

Considering the job opportunities in urban areas compared to

rural areas and the vast difference in average income in the

agricultural sector compared to others, this is not surprising.

Some parents discourage their children from following in their

footsteps because they wish them an easier, more prosper-

ous life. This should not come as a surprise considering that

on average, a farmer will earn around half of what someone

working in another economic sector earns. Combine this with

the lack of infrastructure and services in rural areas compared

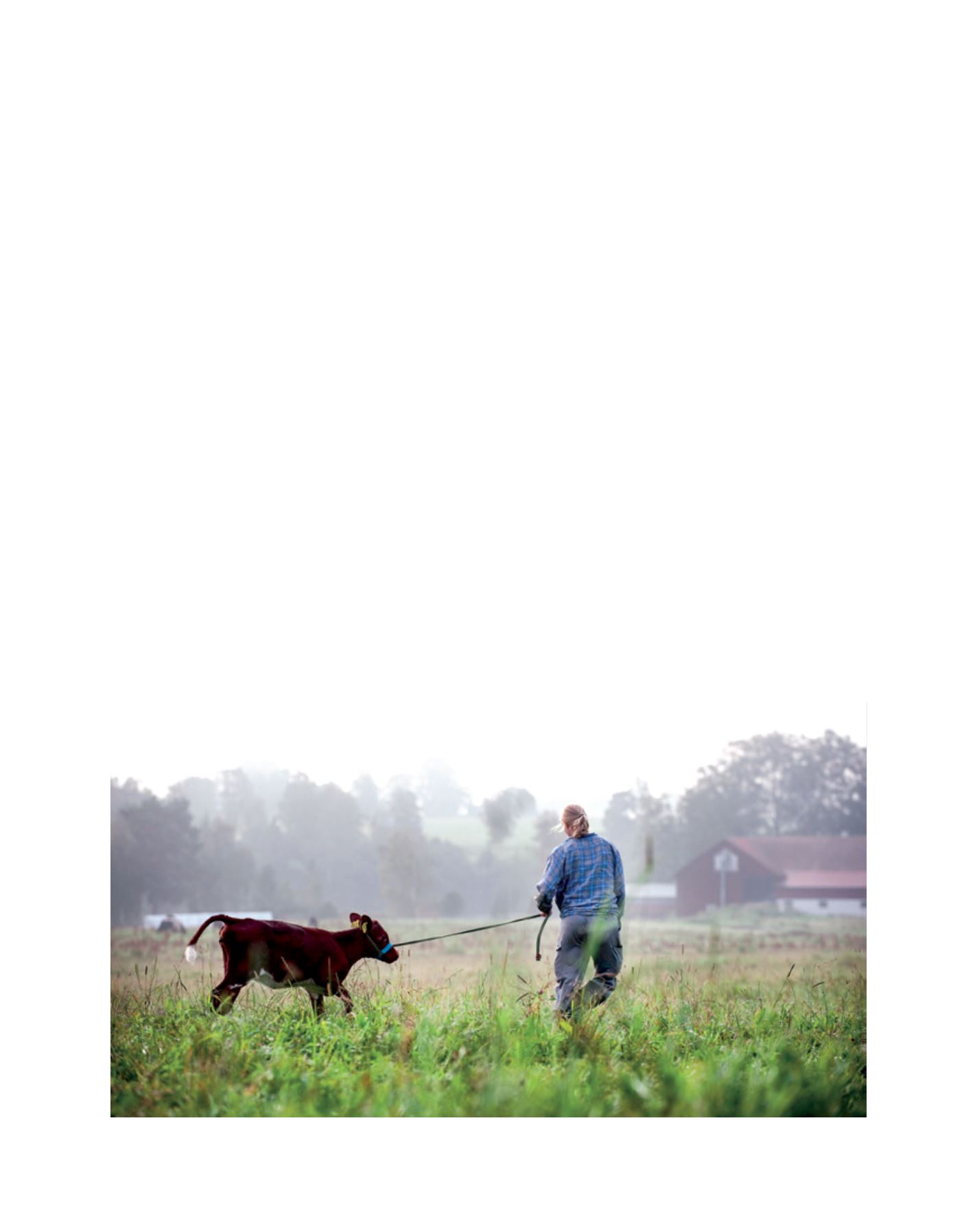

Image: CEJA/Ulf Palm

CEJA advocates a range of support measures to help young farmers get their feet off the ground

D

eep

R

oots