[

] 32

ient. Managing dryland forests in a sustainable way is

a tool of improving the poorest people’s conditions of

living/livelihoods and can thus contribute to meeting

the United Nations Millennium Development Goals

regarding poverty alleviation, eradication of hunger and

protection of the environment.

9

,

10

The UNCCD 10-year strategic plan for 2008-2018 has

specific provisions and expected outcomes for improv-

ing the conditions of the population and ecosystems

affected by land degradation, which leads to deserti-

fication. It promotes sustainable land and ecosystem

management, measures that in turn address poverty –

which is a major cause of forest biodiversity loss – and

increase ecosystem resilience, making the rural poor

less vulnerable to the impacts of land degradation.

Apart from dry forest preservation, the policy-relevant

issue is the promotion of sustainable land management

(SLM) techniques like conservation agriculture, agro-

forestry and soil conservation in arid, semi-arid and dry

sub-humid areas, where tree removal, cropping and

overgrazing result in soil erosion and watershed deple-

tion. Agroforestry in drylands can help in restoring

land, while feeding the poor. It is driving the Greening

of the Sahel in West Africa, where land improvement

trends have been observed on over five million hectares

in Niger. In the 1980s the peasant farmers in south-

ern Niger had to plant their crops three or four times

each planting season because the plants were buried

by wind-blown sand. Today, they typically plant only

once because the forests now protect the seedlings.

tats is low and they receive little attention from conservation efforts.

At the same time few financial investments are allocated for the arid

zones’ forests compared to other forest ecosystems.

Dry areas of the tropics often have different soil types than tropical

wet forest areas, making them better for agriculture. When managed

unsustainably they become degraded. This degradation is far more

advanced than that of wet forest.

7

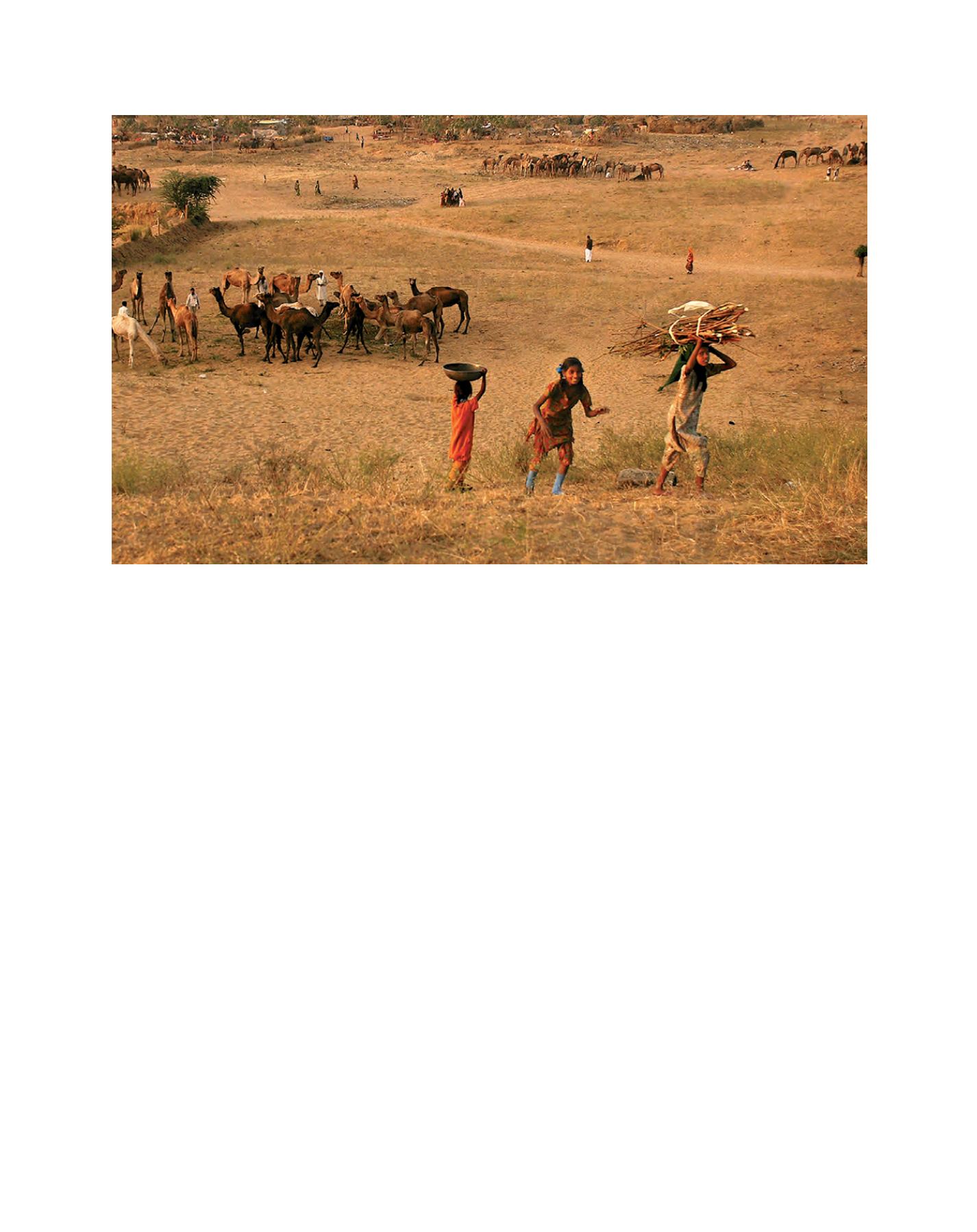

Intensive human intervention,

for example, fire, grazing, agriculture and firewood collection, has

already adversely transformed many dryland forests.

The dry forest systems that have not been completely compro-

mised are generally impoverished and fragmented. The degradation

process thus initiated has led to a shift away from the original vege-

tation types to drier, less productive and less resistant forest types,

exposing large numbers of people to the threat of desertification

and associated disastrous ecological, social, and economic impacts.

Furthermore, loss of vegetation causes biodiversity loss and contrib-

utes to climate change through reducing carbon sequestration and

lowering resilience.

Hence, it is not surprising that the Global Forests Resources

Assessment of 2010 published by the FAO claims that: “The protec-

tive functions of forests are more important in the arid zones than

elsewhere.” By providing ecosystem goods such as fodder, fuel,

wood for construction, medicines and herbs, forests meet the

primary needs of some of the world’s poorest populations. Trees also

stabilize the soil, which prevents soil erosion and helps to conserve

water. In short, dry forests are a buffer against drought and deserti-

fication and a safety net for the poor.

8

Despite suffering from greater degradation than wet forests, dry

forests have the potential to recover to a mature state more quickly

than wet forests and they may, therefore, be considered more resil-

Human interventions cause forest degradation in drylands

Image: Subir Gupta - UNCCD photo contest 2009