[

] 64

improving the fertility of soils and increasing productivity of the

land. Trees also provide erosion control, improve water infiltration,

provide land cover and shade and act as windbreaks.

In Senegal, planting strips of

Casuarina spp

. in the Niayes coastal

stretch north of Dakar has stopped the movement of sand dunes and

provided shelter from the sea winds that made any type of agricul-

ture impossible. Market gardening is now thriving and provides a

livelihood to an increasing number of settlers.

Fertilizer trees which capture nitrogen from the atmosphere and

transfer it to the soil provide a low cost way for farmers to improve

soil fertility and boosts crop yields. In Malawi, Zambia, Kenya,

Tanzania, Niger, Burkina Faso and other countries in sub-Saharan

Africa, fertilizer trees are doubling and tripling average maize yields.

In pastoral areas of sub-Saharan Africa, three-quarters of the

10,000 tree and woody species are used as fodder, supplying up

to 50 per cent of livestock feed, particularly during the dry season

when grass and crop leftovers are scarce.

In Shinyanga, Tanzania, a comprehensive soil conservation and

agroforestry project has seen the planting of 500,000 hectares of

woodlots which supply feed for animals in the dry season. As a

result, smallholder farmers have seen their profits rise by as much

as US$500 per year.

Realizing agroforestry’s full potential

Agroforestry is complementary to the three UN environmen-

tal conventions with enormous potential to increase biodiversity

conservation, address climate change and combat desertification.

It also contributes to development objectives, offering multiple

livelihood benefits to smallholder farmers, including: diversified

income, resilience to risk, nutritious foods, medicines,

green fertilizers, timber, fuel wood and fodder. But what

will it take to increase the adoption of agroforestry on

a global scale?

Current interest in payment for environmental serv-

ices (PES) schemes seeks to reward those who provide

environmental services on behalf of those who benefit.

In many cases, financial transfers are not the primary

issue. To improve the livelihoods of people in upland

areas often requires resolution of conflicts over land

use rights, recognition and respect, and access to the

educational and health services that beneficiaries of

environmental services take for granted. Experience

from World Agroforestry Centre programmes, RUPES

in Asia and PRESA in Africa, has shown that reward and

co-investment schemes that start from the needs of rural

poor and consider options for land use change can make

a difference beyond the financial value of cash transfers.

In the case of agroforestry, such environmental services

include conserving biodiversity, storing carbon, prevent-

ing degradation and protecting watersheds.

Under the United Nations Framework Convention

on Climate Change, nations can agree to participate in

schemes that will reduce emissions from deforestation

and forest degradation. At the local level, this may well

result in reward and recognition schemes that remove

bottlenecks for farmers to benefit from growing trees

on their farms.

Research has shown that successful PES initiatives

must be long-term commitments and accountability

for environmental outcomes is more effective than

payments for labour and effort. Because trees are

usually a long-term investment, up-front payments may

be needed to encourage the adoption of agroforestry.

The need to overcome policy constraints is still

holding farmers back from taking full advantage of

growing trees on their farms. In 2010 the World

Agroforestry Centre launched the Agroforestry Policy

Initiative which is designed to kick-start a global review

of outdated policies and forest regulations.

Improved policies would see better coordination

among different ministries that would promote clear

tenure rights to land, forests, and trees, thus improving

farmer access to agroforestry information and germ-

plasm, and creating integrated competitive and fair

markets. For example, following reforms to the Code

Forestier in Niger, farmers have again been cultivating

trees and the country has seen a tremendous increase

in tree cover on over 5 million hectares in the past 20

years.

10

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the

United Nations is developing agroforestry guidelines for

national policies and decision-making with the involve-

ment of key development and research institutions.

Greater investment is needed to support smallholder

farmers in adopting agroforestry practices – such as

provision of tree planting material, information and

training, access to credit – so that they can improve

incomes and ensure food security while at the same

time providing environmental benefits.

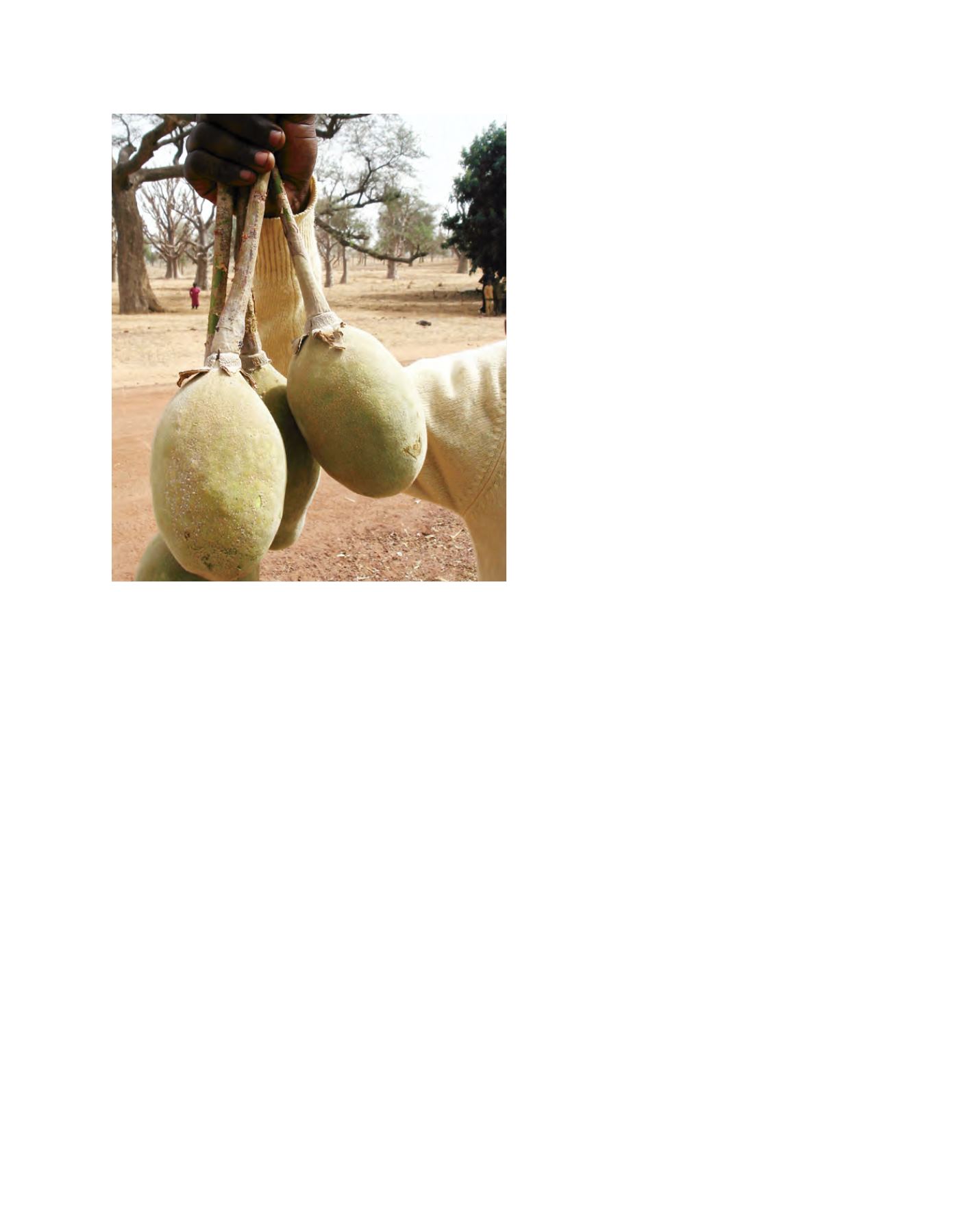

Baobab fruits in Niger

Image: Julius Atia/World Agroforestry Centre