[

] 11

L

iving

L

and

on the expert judgement of scientists. It produced a world

map of human-induced soil degradation and concluded

that 15 per cent of the land surface was degraded. But it

got outdated quickly.

The first comprehensive assessment of the status of deser-

tification, land degradation and drought on a global level

is the 2005

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment

(MEA). It is a

well-researched presentation of the status and the economic,

social and cultural values of the dryland regions of the world.

It brought to the attention of the international community

the consequences, at the global level, of failing to combat

land degradation or mitigate the effects of drought. The MEA

remains a valuable resource for policymakers, activists and

the scientific community. But it focuses on drought and land

degradation in fragile ecosystems only, that is, the arid, semi-

arid and dry-sub-humid zones of the world. Thus, it does

not tell us the status of land degradation worldwide. And the

publication is still fairly technical, which has kept it inacces-

sible to the general reader, in spite of its immense value.

The

Global Assessment of Land Degradation and Improvement

(GLADA) was published in 2008 and offers a deeper analysis

of land degradation.

2

It reveals the scope of land degradation

in all types of ecosystems and the global population affected,

but also probes where land is improving. Indeed, a fair assess-

ment of the status of land degradation must take into account

the amount of degrading land and the unproductive land

being restored back to health.

According to GLADA, 24 per cent of the global land area is

degrading. Some of these are new areas and not just in Africa.

Land degradation was also evident in Australia, Asia, Latin

America and North America. In short, this is a global phenom-

enon. GLADA uncovered other significant results. About 78

per cent of the degrading land is not in the dryland areas, but

in the humid areas; 16 per cent of the land area is improving;

and 1.5 billion people depend directly on degrading land. The

study also drew attention to the release of greenhouse gasses

through land degradation. In spite of the study’s ground-

breaking data, its highly scientific orientation means it didn’t

capture the imagination of the general public.

At about the time the study was released, the international

community celebrated the International Year of Deserts and

Desertification. In light of a persistent lack of awareness about

the scope and causes of desertification and the solutions to the

problem, the United Nations General Assembly declared 2010 to

2020 the United Nations Decade for Deserts and the Fight against

Desertification. The purpose of the decade is to raise global

awareness of desertification, land degradation and drought at all

levels. This year, 2015, marks the half-way point of the decade.

What has changed?

The adoption of the 10-year (2008-2018) strategic framework

for the implementation of the Convention was a watershed

moment in the global efforts to combat land degradation. It

embraced science as the guide to policymaking in the global

efforts to combat land degradation and drought. The science

is today more robust and growing, and the Science and Policy

Interface (SPI) established in 2013 is facilitating dialogue

between scientists and policymakers.

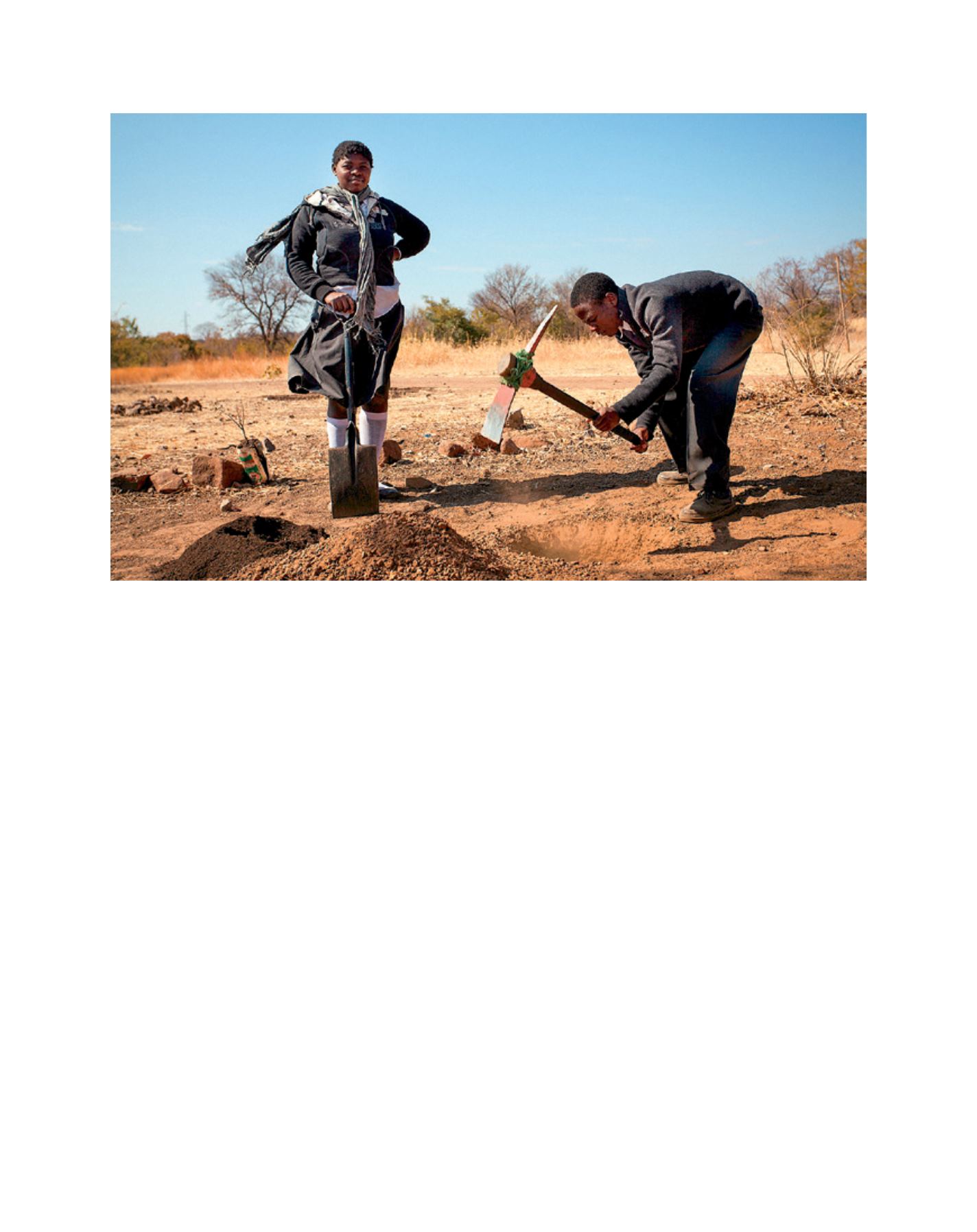

More than 1.5 billion people depend on degrading lands, but land degradation is not fated, where there is political will

Image: Ricardo Spencer & UNCCD 2013 Photo Contest