15

intent and then execute the work

with greater accuracy.”

John Fought, ASGCA, also

referred to the Tufts Archive when

restoring the original Donald Ross

design at

Pine Needles CC

in

North Carolina. “We utilized old

aerial photography, Ross’s concept

plan and many photos from the

original construction,” says Fought.

“These materials help the current

generation understand the changes

that have occurred, both manmade

and through natural evolution.”

And for his ongoing work at

Rosedale in Toronto, Fought has

transposed the course as depicted

in a 1939 aerial over a plan of the

existing golf course.

Aerial photography can be

invaluable. “At the start of our work

at

River Vale CC

in New Jersey, the

club provided several high quality

aerial photographs that helped us to

pinpoint the ‘moment in time’ that

we wanted to embrace relative to the

bunker styling,” says Robert McNeil,

ASGCA. “This photography provided

some clarity and comparative

information relative to the classic

style of 1944 versus the ‘saucers’

created in the 1960s.

“What this photography also

presented was the original mow

lines on the golf course as well as

several bunkers that had been lost

or moved over the years. From this

we were able to scale the bunker size

and perimeters, locate the original

fairway mow lines in the field and

develop a reasonable and effective

tree management program.”

McNeil continues: “One of the most

important foundational elements

of restoration is to establish a

respectful understanding of what it

is you are attempting to restore. This

is sometimes challenging as each

golf course evolves from its original

design, strategies and style.

“It is common for a greens

committee or chairperson to boldly

state ‘we want all the bunkers exactly

like they were when the course

was originally built in 1900-and-

something.’ This is where the architect

can guide the research and develop

restorative directives that are sensible,

reflect the true character of the

golf course and embrace historical

elements and characteristics that fit

into the current layout and demands

of the game.”

•

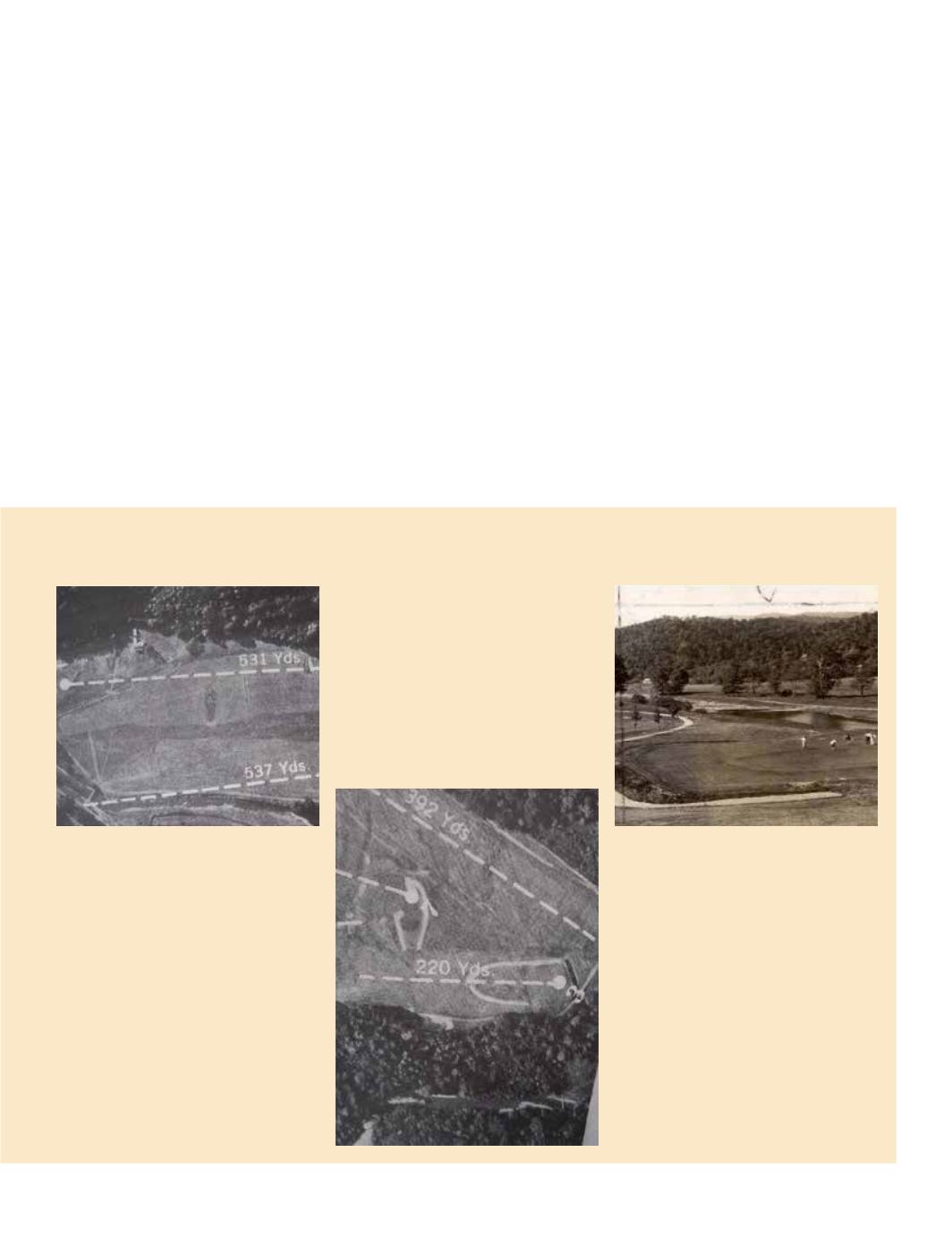

“On the third hole (below) you can see

the Biarritz and the horseshoe-shaped

bunker around it. For resort play, as the

bunker goes all the way round, a forced

carry on a 220-yard hole is pretty tough.

So we took some artistic license and put

in Biarritz bunkering like we’d seen it

at other courses, which is left and right,

front and back. These are the kind of

decisions we had to make.”

“At the top of the photo (above) is the

twelfth hole, and to the right of the ‘s’

of ‘Yds’ is a bunker, with the sand and

the brow visible. I restored that bunker

as part of my work there. Further down

the fairway there’s a section that looks

like tall grass, or a blip if you will on

the left hand side. That’s where the hell

bunker would have been. Between

there and the green there’s a creek,

and you can see where the fairway

comes down to a point. We restored

the creek and put sand back into the

hell bunker. These are the kind of

things we were able to pick up thanks

to the photograph.”

“The 18th green (above) has the

horseshoe contour in it, which Raynor

and McDonald always put in their short

hole. So when I built the 18th green

back as it was, I built a remnant of it as I

didn’t have the room to go all the way to

the creek anymore. It’s a brow and it’s in

the middle of the green, and the first year

they held the Greenbrier Classic there

people were saying ‘What the hell is

this? It’s three feet high!’ We reintroduced

it to keep it fun for the resort golfer, but

when the tour came they asked whether

to keep it, and I said ‘only if you want to

be accurate!’ Now it’s one of the most

talked about holes on the PGA Tour.”