L

ocal authorities have responded

to the drought conditions

throughout the South and

West of the United States by offering

rebates for golf clubs that reduce the

amount of maintained turf on their

courses. Less turf means less water

is required, and that alone can justify

such projects.

But even where rebates are not

available, clubs are finding that a

reduction in turf can deliver cost

savings in other areas – such as

power and maintenance – and a host

of additional benefits, including an

aesthetic that is better suited to modern

tastes, fewer lost balls and a faster pace

of play – all of which can contribute to

increasing numbers of rounds.

The trend towards a more natural,

rustic-looking golf course has been

progressing steadily over the past

fifteen years or so. Often inspired by

an admiration of the work of Golden

Age golf architects who did not

necessarily have the technology to

maintain a lush golf course, today’s

designers are increasingly less likely

to propose wall-to-wall turf, even

where water is freely available.

And the golfing public’s taste is

following suit, evident from the

popularity of more traditional golfing

experiences such as those available at

the Bandon Dunes resort in Oregon and

the overwhelmingly positive response

to the work of Bill Coore, ASGCA, and

Ben Crenshaw at the No. 2 course in

Pinehurst, North Carolina, the host

course for last year’s U.S. Open and U.S.

Women’s Open championships.

As more natural-looking golf courses

get greater exposure, clubs may find

their members and guests having a

greater appreciation of a less manicured

style. And even if they don’t, they may

well find themselves getting greater

enjoyment from courses that don’t

punish the golfer with thick rough.

A golf course architect can help

identify the most suitable turfgrass

reduction program for any given

course, which will be dependent

on soil conditions, climate and a

number of other factors. They can

then recommend a step-by-step

process from the identification of

areas suitable for removal to the

adjustments that may need to be

made to the irrigation system.

Many turf reduction programs –

such as the one referenced earlier

in this issue at the Roadrunner

course at Hogan Park in Midland,

Texas – are seeing expanses of thick

rough replaced by natural waste

areas. It’s still a punishment for the

errant golfer, as the ball may find an

awkward lie among native plants or

unraked bare ground. But it can be

much easier to find your ball and

continue your round in this barren

landscape, or among woodchip or

pine straw, that it is in deep rough.

For most regular golfers, the avoidance

of lost balls can have a very positive

impact on the enjoyment of golf, and if

golfers are spending less time looking

for balls, the general speed of play will

increase too. Faster play equals more

capacity equals increased potential

revenue for the club.

•

Turf reduction

|

Toby Ingleton

Less turf, more play?

CLOSING THOUGHTS

For more information on the benefits

of turf reduction and how a golf course

architect can help, download the free flyer

at

www.asgca.org/free-publications26

|

By Design

Water and cost savings are usually the drivers for turf reduction

programs. But they are not the only benefits, says Toby Ingleton

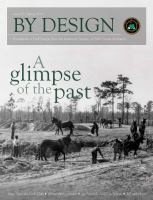

At Oakmont CC in Glendale, California, Schmidt-Curley’s turf reduction work also significantly

improved aesthetics