10

|

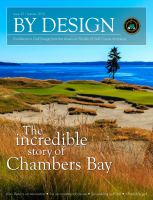

By Design

largest source of sand and gravel

into a championship links was a

monumental task of political will,

inventive engineering, and meticulous

planning. The process started in

1992, when the county’s wastewater

treatment district purchased the site

for $43 million from mining firm

Lone Star Northwest with plans for

establishing a water treatment facility

there and reclaiming some of the

unused portion for public use.

The setting for what was initially

termed Chambers Creek was ideal

for recreation—along a two-mile

stretch of lower Puget Sound, with

clear views of the Olympic Range and

with pedestrian access from a near

highway that brought folks from the

country’s 15th largest metropolitan

area (Seattle-Tacoma) to the very

rim of the cored-out parcel. In

what would turn out to be a crucial

decision, Pierce County officials

retained the permit to mine the site.

They didn’t know it at the time, but

without that residual right they could

never have built the course.

Ladenburg, an elected official, was

inspired by the fact that municipally

owned and operated Bethpage State

Park-Black Course in Farmingdale,

New York had landed the 2002

U.S. Open. He knew the U.S. Golf

Association had been searching for a

suitable Pacific Northwest site for its

premier national championship and

began to formulate a plan.

Critics, including many county

residents, derided what came to be

known as ‘Ladenburg’s Folly.’ But

he was convinced and stuck his

neck out by pushing for the project,

often having to work hard to achieve

favorable 4-3 votes from the County

Council on permitting, planning and

issuance of special revenue bonds

to the tune of $22.8 million, payable

over 30 years. He knew the crucial

difference in quality, he says, between

getting something 99-percent right

CHAMBERS BAY

The RTJII team presented Pierce County with two options for the course: a 27-hole design as requested, plus a more expansive 18-hole option