12

|

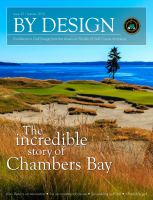

By Design

the plant on the far south end of the

entire property.

Ladenburg also made a crucial

determination—to go with links-style

fescue grasses that would emulate a

traditional seaside layout, and with

that, to abandon any paved cart paths

and to rely upon a walking-only policy

for play rather than one that catered

to modern preferences for riders.

Carts would have beaten fescue into

submission. A walking policy, with the

occasional concession to medically-

certified golfers incapable of walking,

would protect the notoriously

traffic-intolerant grasses needed for

a true links layout. KemperSports,

the management firm that had been

overseeing the all-fescue Bandon

Dunes Resort in Oregon since its

inception in the late-1990s, knew that

the virtual banning of carts would

have serious financial implications

for the Chambers Bay operation. But

Ladenburg was insistent, and instead

of being a liability, the emphasis upon

walking became a defining element of

the property.

An abundance of sand on site

meant that there was plenty of

available material for a fertile growing

medium. But first the land had to

be rough shaped into proper form.

That required an army of bulldozers

and pan scrapers—25 heavy pieces

of machinery, all of it part of a

construction contract awarded to

Heritage Links, with Jones’ own

shapers, Ed Tanno and Doug Ingram,

leading on the all-important final

massage work.

At times, the yearlong construction

process looked like a scene from a

post-apocalyptic sci-fi movie. The

grading operation required a kind of

‘melting down’ of the entire northern

rim by 10-25 feet, with the material

then screened in massive sorting bins

that were themselves holdovers from

the old gravel site. The sandy material

was tested for percolation rates and

moisture retention, then used as

capping for the areas to be grassed.

Jones, watching as the elevation levels

of the site evened out somewhat,

likened it to “an acceleration of

geological time.”

Rarely has a North American

construction site made quicker

progress from ugly to beautiful. An

entire ridge was pushed through to

make way for the 10th hole. Today,

it looks like the hole was fitted into

a natural box canyon, with just an

opening at the far end to give a glimpse

of Puget Sound behind the green.

In an effort to give the resulting

mounds and knobs some element

of rough, scruffy nature, track

hoes plodded up and down them

to imprint their tracks on the

dirt; this had the double effect of

creating a corduroy effect that would

hold emergent turfgrass down as

it germinated in the wind. The

furrowing also made it look as if age-

old erosion had already taken hold.

Once the fescue took hold and started

waving in the breeze, the entire site

took on the feel of a classic links, one

that had been there for decades.

Oh, those finicky fescues.

Notoriously hard to establish and

sustain, particularly in a cool-season,

rainy environment. Interestingly,

metro Tacoma, with 40 inches of

precipitation a year, is closer to

St Andrews (27 inches) than to

Bandon, Oregon (59 inches) in

the wet department. Specifications

were precise and based upon test

plots cultivated 20 miles to the east

in Puyallup, Washington. Greens,

fairways, tees and approaches were

seeded to a mix of colonial bentgrass

(6 percent), a three-way mix of

CHAMBERS BAY

Project Timeline

Pierce County acquires a

930-acre gravel and sand

pit along Puget Sound

The firm of Robert Trent

Jones II wins the golf

course design contract

Pierce County Council

authorizes construction bonds

for golf course

Construction begins

Mike Davis, th

senior director,

competitions,

to Chambers

1992

Pierce County executive John

Ladenburg initiates plans for a

golf course and park

2002

Mining ends but county

retains mining permit

2003

2004

2005

2005

2006