[

] 122

Livestock and women

Almost two-thirds of the world’s 1 billion poor livestock

keepers are rural women, although their ability to control

livestock assets and incomes differs by their cultural and

economic settings. In many cases, women’s ownership

of stock does not correlate with their control over use of

products or decision-making regarding livestock manage-

ment or sales. Women often control small stock such as

poultry, as long as this remains a small-scale enterprise.

Women often may own the milk from cattle while men

control the income from animal sales. Among some socie-

ties in Senegal, dairies are often run by women and milk

production is controlled entirely by women, who have sole

control also over the sale of any surplus milk.

11

Women

also manage activities at different stages along livestock

value chains, not just as producers or traders but also as

cottage processors of traditional value-added products such

as cheese, sweets and dried and ready-to-eat cooked prod-

ucts. In traditional dairy production practices in Ethiopia,

women who process and sell butter and cheese earn 69 per

cent of the household dairy income.

12

Local economies

Beyond the farm gates, livestock keeping benefits the local

and wider economies in many ways. What is often under-

appreciated is the level of local employment by livestock

family farms, even those with only a small enterprise. Many

small farms hire part-time and even permanent full-time

labourers to assist with tasks like livestock feeding and

cleaning. A study in Kenya found that half of the coun-

try’s many small family dairy farms (most with fewer than

three head of cattle) hire at least one full-time labourer.

13

These workers are often from the most resource-poor and

marginalized communities, so these are important oppor-

tunities for employment and livelihoods for the most

disadvantaged. In rural communities, some individuals

also provide informal or formal animal health or breeding

services, gather feeds for sale to livestock keepers or estab-

lish ‘agro-vet’ shops to sell animal feed and health products.

Numerous other economic and employment activi-

ties, for women as well as men, occur along the livestock

product supply chain, from the most basic collection by

small traders of livestock or products for assembly and

further sale along the chain (which in pastoral areas can

comprise very long distances and sequences of intermedi-

aries) to quite sophisticated local processing of speciality

products such as high-value dairy sweets.

In most developing countries, these livestock supply chains

tend to be ‘informal’ or ‘traditional’, meaning they don’t

employ modern processing or handling methods but deal

with either raw, unchilled or traditionally processed products.

Although these informal markets generally don’t meet official

standards, they still comprise the largest share of the livestock

subsector in most developing countries.

Importantly for the local economy, the retail prices

of such informal products are nearly always lower for

consumers than alternative ‘supermarket’ products,

generating economic gains to consumers. And informal

markets tend to employ more people per unit of product

than modern, capital-intensive product supply systems.

Studies across Africa and South Asia found that informal

milk markets employ two to five times as many people per

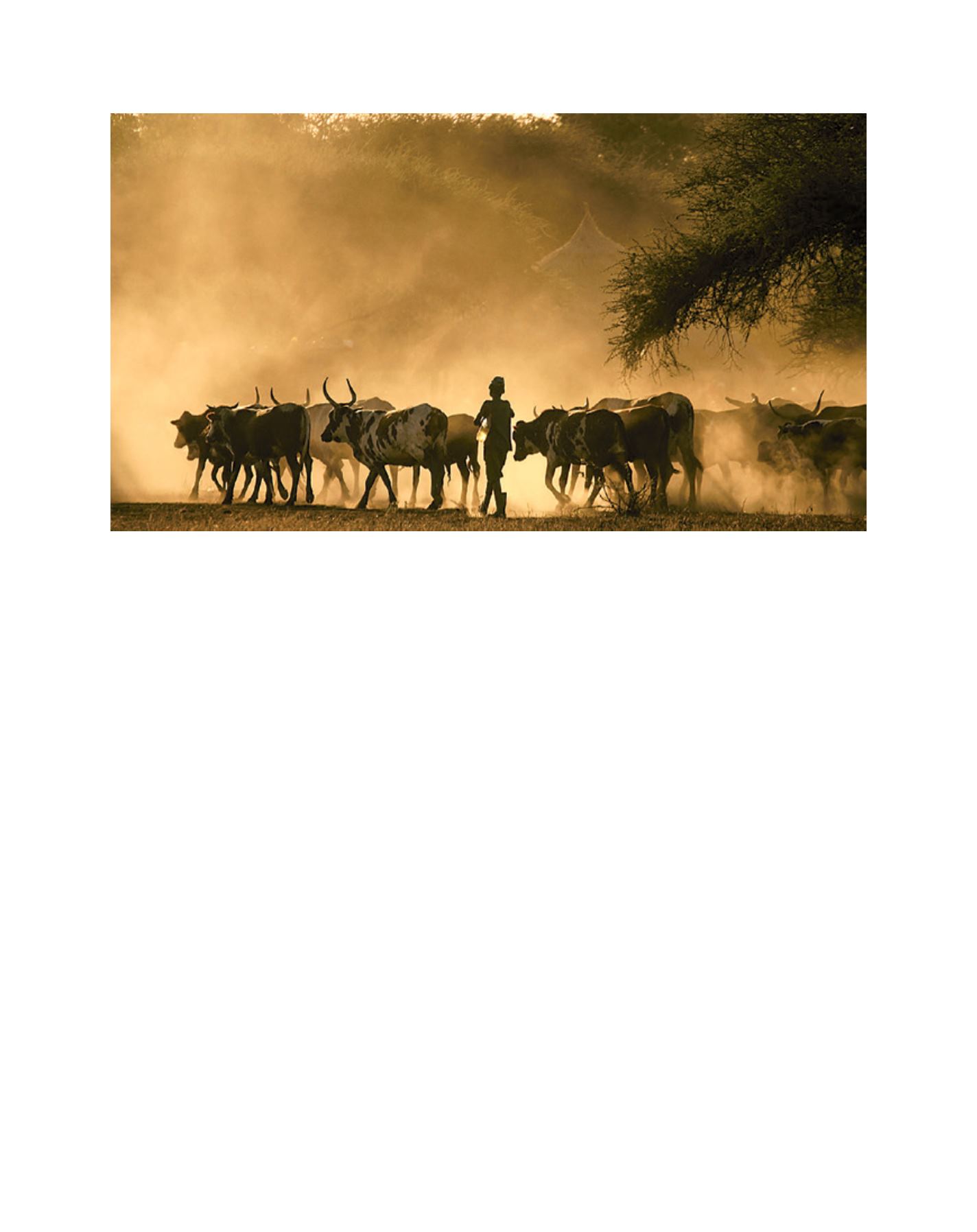

Image: ILRI

Livestock are the only practical means of harvesting the benefits of scarce moisture in drylands and other regions where

the climatic conditions are unsuitable for crops

D

eep

R

oots