[

] 121

settings. Research has shown little evidence of economies

of scale at play in dairy production in Asia and Africa, for

example, particularly where the opportunity costs of labour

are low and incentives for mechanization limited.

4

Small

family-run pig enterprises in Viet Nam were also shown to

operate with similar or lower unit costs than larger enter-

prises.

5

The family nature of livestock enterprises is central

to this competiveness.

As a result, small family farms produce 70 per cent of

the milk in India, now the world’s largest milk producing

country; more than 90 per cent of meat from sheep, goats

and chickens; and 70 per cent of beef. In Viet Nam, where

some agricultural subsectors are intensifying rapidly, small

farmers still produce 90 per cent of the supply of pork, the

most popular and important meat product in that country.

These small farm shares are expected to decline in future

with rural-urban migration and changing technologies, but

the opportunities for tens of millions of smallholder live-

stock farmers across several continents to improve their

lives and livelihoods through livestock will continue for

decades to come.

Household livelihoods

While clearly important for family livestock farms in the aggre-

gate, livestock are also economically important at individual

household level. As one measure of that importance, nearly

1 billion people living on US$2 a day or less in South Asia

and sub-Saharan Africa keep livestock. More than 80 per cent

of poor Africans keep livestock, and 40-66 per cent of poor

people in India and Bangladesh keep livestock.

6

In many rural

settings, livestock production comprises the most important

part of individual household incomes and livelihoods.

Also seldom recognized is that keeping livestock often

does not require land owning or even land-use rights.

Intensive specialized livestock production can be carried

out at the homestead with feed bought, exchanged or gath-

ered from other sources. Analysis in Kenya found that the

size of land holdings is not associated with a family’s ability

to keep dairy cows.

7

In India, where rural and urban land-

lessness is an ongoing problem, the number of landless

dairy producers has been increasing.

A study of 92 cases from the developing world found

that livestock contributed on average 33 per cent of income

from all sources on mixed crop-livestock farms, with higher

proportions associated with market-oriented dairy and

poultry production.

8

The importance of livestock tends to

increase in drylands and other regions where growing crops

is nearly impossible for climatic reasons and livestock are

the only practical means of harvesting the benefits of scarce

moisture. In these largely non-arable lands, the study

found average livestock incomes from pastoral production

comprises 55 per cent of total household incomes.

The shares of household income from livestock are not

only typically large but also growing in many cases. While

the share of income from cropping remained stable or even

declined, the share from livestock grew in just six years

by 75 per cent in Ghana and by 110 per cent in Viet Nam

(1992-1998) and by 290 per cent in Panama (1997-2003).

9

This is partly because as smallholder households transi-

tion from subsistence to market-oriented agriculture, they

prefer marketing high-value meat, milk and eggs to selling

crops, which are often of lower value. Livestock thus plays

an increasingly large role in the market income of small-

holder households as farms shift to market-orientation and

away from subsistence.

An important aspect of household incomes from live-

stock is that the daily surplus of milk and eggs is a ready

(and rare) source of regular cash income in poor rural

environments. Livestock also offers unique economic and

livelihood benefits. As an inflation-proof means of accu-

mulating assets, livestock serve as insurance instruments

for maintaining funds for medical and other emergencies

and as a means of saving planned expenditures such as

school fees or small business investments. These are criti-

cal matters in resource-poor communities, where formal

insurance schemes and savings mechanisms are often

nonexistent. Here, medical emergencies can produce

life-long poverty traps. Even small stock such as goats or

poultry, which are often in the control of women, are used

for lumpy expenditures such as utility bills.

Finally, in many communities livestock keeping improves

a family’s social capital, improving access to other commu-

nity services and functions. Remarkably, estimates of these

‘non-market’ benefits of livestock keeping can amount to

an additional 40 per cent on top of cash profits.

10

Such

non-market benefits are generally not available to large

commercial producers, for whom livestock assets are sunk

costs rather than assets accumulated through low-cost

labour and local feed resources.

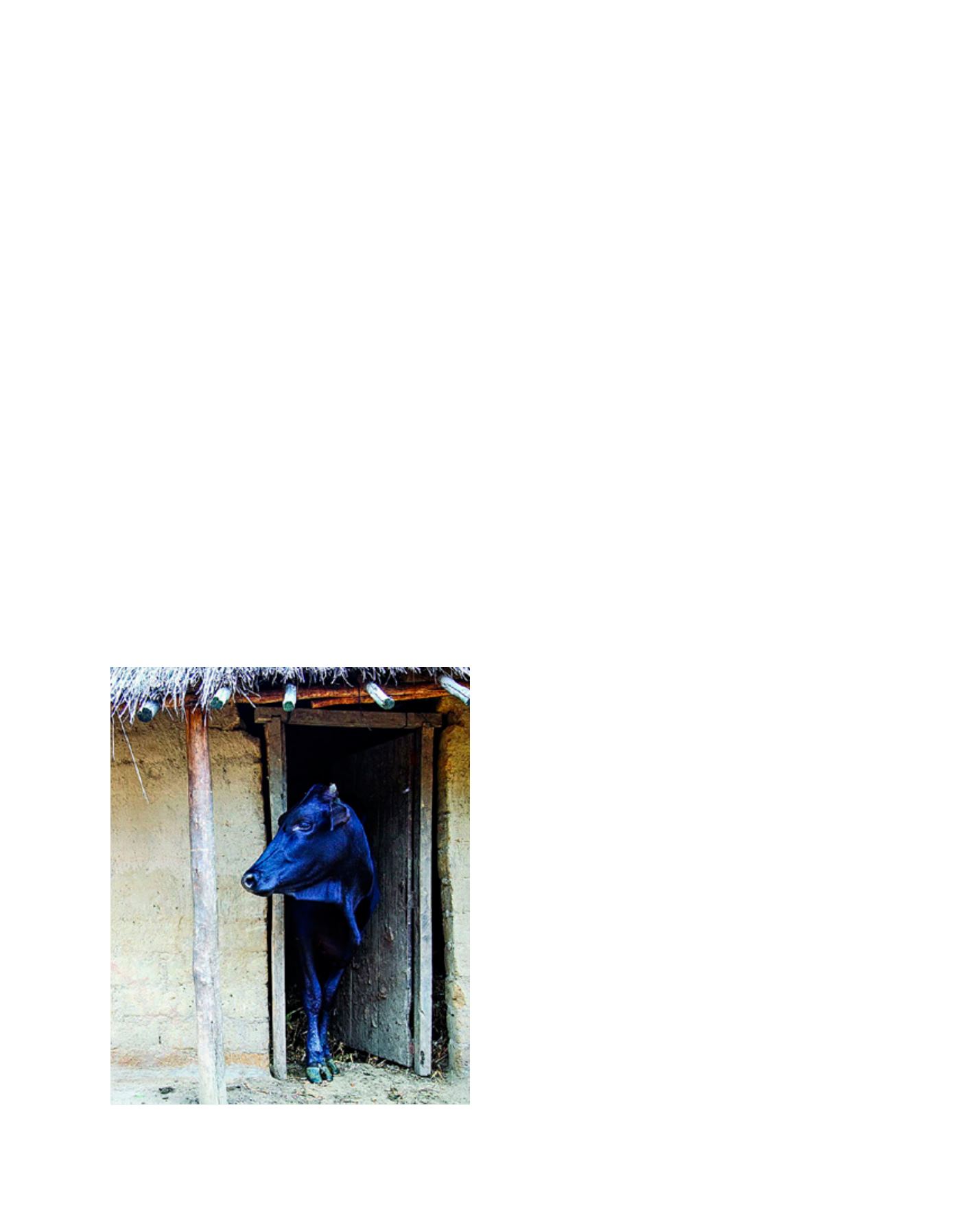

Smallholder family farms still dominate livestock production – especially with

ruminant animals – in most developing countries

Image: ILRI

D

eep

R

oots