[

] 116

Assuming an average of 145 tons per hectare of growing stock,

the biomass accretion to the soil from leaf fall over the year

could range from 14.5 to 29 tons per hectare. This leads to

incremental year-round organic carbon accretion to the soil,

which is fundamental for soil health, water holding capacity

and fertility. Although leaves represent only around 10 per

cent of total plant biomass, their high nutrient concentration

makes them a major sink for nutrients, representing 37 per

cent, 23 per cent, and 20 per cent of total nitrogen, phospho-

rus and potassium respectively in bamboo.

A second source of organic carbon and nutrients is the

rhizomes and roots. Bamboo grows only in the topsoil

(commonly 50-75cm deep) and hence benefits this economi-

cally important soil layer. It has an elaborate rhizome, root,

and root hair system that sequesters 31 per cent of the

total biomass with 69 per cent being in the poles (culms),

branches and leaves. Of this below-ground biomass, 34 per

cent is due to rhizomes and 66 per cent to roots in clumping

bamboo species.

A third key strategy is to secure better returns on rural

savings. Rural women are the backbone of rural savings.

Poor rural women incrementally build up a corpus of savings

through self-help groups, savings and credit cooperatives.

While savings are built up, there are few productive and

low-risk investment opportunities. The cooperatives mostly

lend at 6 per cent interest for the commodity trades they

are involved in, which is the return the women receive after

deducting costs. In comparison, inclusive social enterprises

can offer better returns since they currently source working

capital (debt) at 16 per cent interest, which benefits only the

financing agencies. On the other hand, if the rural women’s

cooperatives would lend to them, then they would earn an

additional 10 per cent.

There is a lot that rural savings and investments can do for

the communities themselves. For example, an HHC enter-

prise can be set up by 12,000 women, each contributing

Rs120 (US$2), to a total of Rs1.44 million (US$24,000). The

intrinsic risk to a single woman is low since Rs120 is about

what they earn in a day in India. The women would thus have

shares in the enterprise and get dividend income, and further

benefit by selling their HHC to it.

A novel NGO-community-professionals partnership

(NCPP) concept has also been developed and implemented in

two enterprises, one in Tanzania and one in India. It is based

on the healthcare model where the hospital/clinic-doctor/

nurse-patients are the key stakeholders and investments are

made into the entire system. Likewise for the development-

care ecosystem, enterprises set up on the NCPP model would

have diversified equity to reduce risk and make development

more sustainable. The proportion of shareholding in NCPP

could be approximately 30 per cent from the NGO, 30 per

cent from the Community, 30 per cent from development

professionals (such as those in the NGO), and 10 per cent

‘sweat equity’ for technical assistance.

The robust field-validated initiatives and strategies discussed

above are hugely scalable and replicable around the world. In

India one key modality is the many large NGOs, which grew

mainly during the heyday of microfinance with outreach to

tens of thousands of rural households. Such NGOs offer an

opportunity to mainstream bamboo growing, agribiomass

briquetting and power production, and HHC, including

leveraging their communities to self-help by investing in the

processing enterprises themselves through the NCPP enter-

prise model. Together, these would not only enhance the

resilience of poor rural households but also greatly enhance

their income and raise the quality of life.

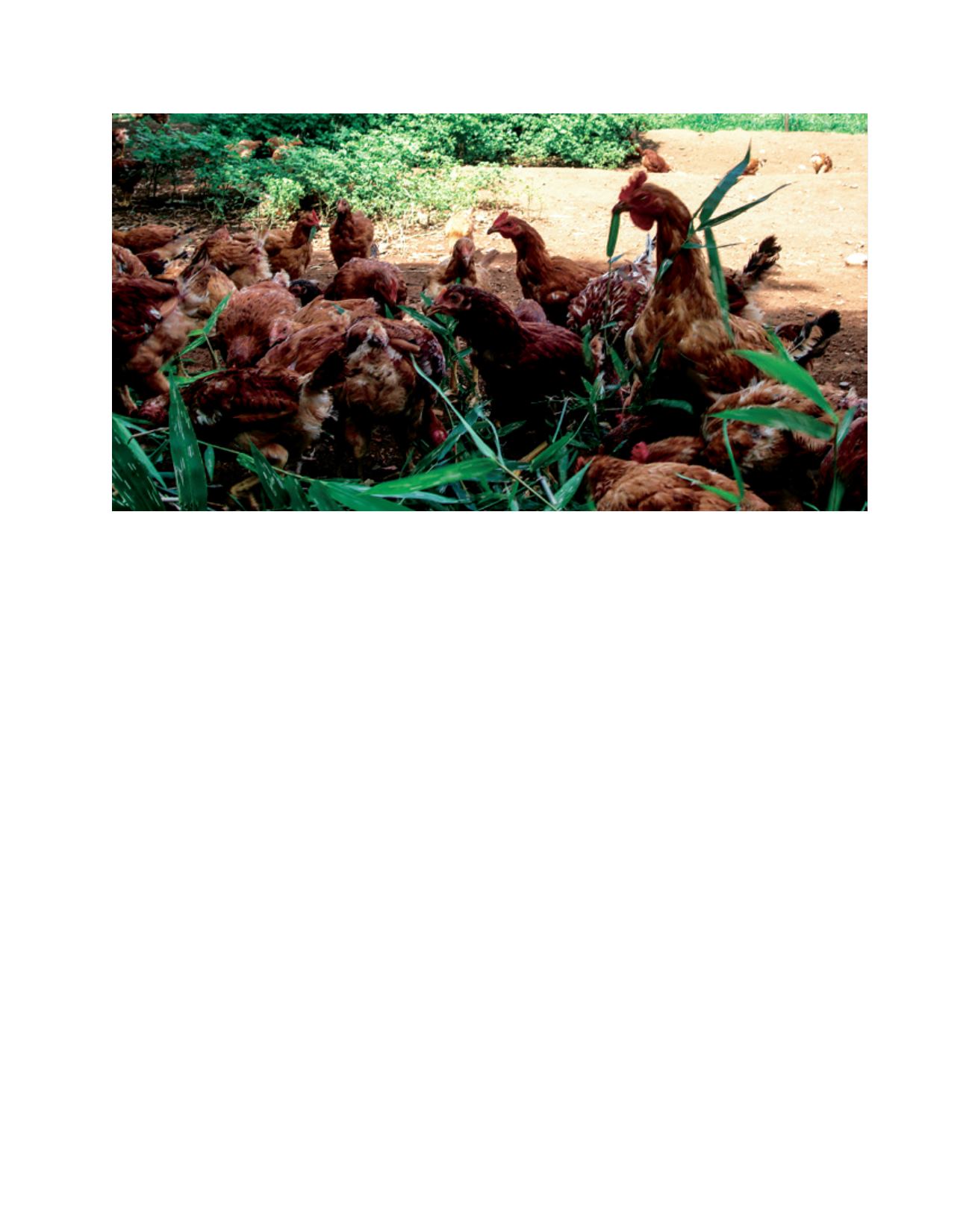

Chickens eating bamboo leaves in the Philippines

Image: Carmelita Bersalona, InHand Abra Foundation

D

eep

R

oots