[

] 115

sale of raw HHC is up to 50 per cent of annual income, and

if briquetted, it reaches 200 per cent. This can be raised

through efficient stoves as described above. Presently,

4,286 women are collecting charcoal in turn, which is

processed by 230 briquetting micro-enterprises each with

one hand-briquetting mould between them. While it bene-

fits all women using fuelwood, single mothers and widows

see a major benefit since they have significantly reduced

household income. The dependability of the income, which

is year-round, makes all the difference. Households derive

income from the collection of charcoal formed during

cooking using fuelwood, from selling the HHC and from

dividends from the three processing enterprises set up

(WODGRA in Tanzania; Shakti and Black Gold in India

with a total installed capacity of 9,000 tons per year which

can benefit 25,000 households).

The stereotype propagated by society and governments is

that farming communities ‘grow’ food and urban communi-

ties ‘buy’ food. The concept of ‘Farmer = Food’ is common

but ‘Farmer = Energy’ is not. The second key strategy for

a robust source of income being advocated by INBAR and

implemented by the Centre for Indian Bamboo Resource

and Technology (CIBART) is that farmers should also grow

biomass crops for fuelwood, for their own use and sale to

others as a mainstream source of income. This is relatively

new for farming households because fuelwood is commonly

gathered from the forest for free, such that biomass was

never valued or thought of as an income source. A change

to ‘Farmers = Food + Energy’ can bring significant benefits

to farmers, enhance their income and quality of life, lead to

resilient livelihoods, release pressure from forests and let

them recover. It would also lead to enhanced areas of perma-

nent green cover.

Bamboo is a miracle crop, perhaps the most versatile of

them all. It is easily the icon of sustainability just as the

Panda is the icon of biodiversity. It is a tree and a grass at

the same time, straddling the sectors of forestry and agricul-

ture. Botanically, bamboo would be classified as a pioneer

species since it can grow on the poorest soils and amelio-

rate them. It can also grow on the richest soils. On poor

soils it would subsist and survive with low production as

in forests, while if fertilized and irrigated as an agricultural

crop, bamboo provides the highest biomass yields of all

woody plants. It is drought- as well as flood-tolerant and

even tolerates complete surface destruction by forest fires

and ‘slash-and-burn’ agriculture. It is a perennial plant that

is annual in behaviour, putting out new poles from under-

ground rhizomes each year. For a farmer it is, therefore, an

annual crop while for the forester it is the perennial tree.

Bamboo plants can be grown by each willing household

in the homestead and farm boundary. Thirty-five bamboo

clumps could generate adequate bamboos for fuelwood and

livelihood use. It would be beneficial to carry this out at

the household level since there is individual ownership and

incentive. Animals need feed, which is commonly in short-

age. Most livestock eat bamboo leaves. In Ethiopia, it is a

staple food for donkeys. Cows and buffaloes eat bamboo

leaves; in upland areas this is often the only green fodder

available during winter. Bamboo leaves can also substi-

tute fish feed for up to 50 per cent. Chickens originated in

bamboo groves and readily eat bamboo even from the broiler

stage. Bamboo fodder and feed is thus part of the food secu-

rity of the household.

Bamboo biomass and agriresidues from the farm are being

used to produce briquettes that industries need for use in

boilers. Currently, four processing units are operational

with a combined capacity of 12,000 tons per year, which is

US$500,000 in new income to the farming households who

would have otherwise burned the residue in the fields.

Such biomass could also be used to generate power: 1.2kg

of biomass produces 1 kWh. A typical bamboo pole of 12kg,

would then be 10 units of power which is more than a rural

household would need in a month. Small-scale biomass-based

power units can act as intermediate markets for local agriwaste

biomass and for empowering rural households to enhance their

quality of life, operate water pump sets, flour mills and the

like, as has been demonstrated in a CIBART project in India.

Globally, 1.3 billion people live in energy poverty.

Growing bamboos would bring several environmental

benefits including soil amelioration and the rehabilitation of

degraded lands. In Allahabad district in Uttar Pradesh in India,

the growing of especially bamboo helped rehabilitate tens

of thousands of hectares of fertile farmland degraded by the

removal of topsoil for brick-making. This won the US$1 million

Alcan Prize for Sustainable Development. The 68 million

hectares of degraded land in India, and 500 million hectares

in Africa can similarly benefit from bamboo planting, as can

the rural households in those areas. This includes abandoned

farmlands, which can be rehabilitated and made productive.

While the average biomass of the leaves on the plant at

any time is around 10 per cent, this does not account for

the leaves that have dropped over the year (say 10 per cent).

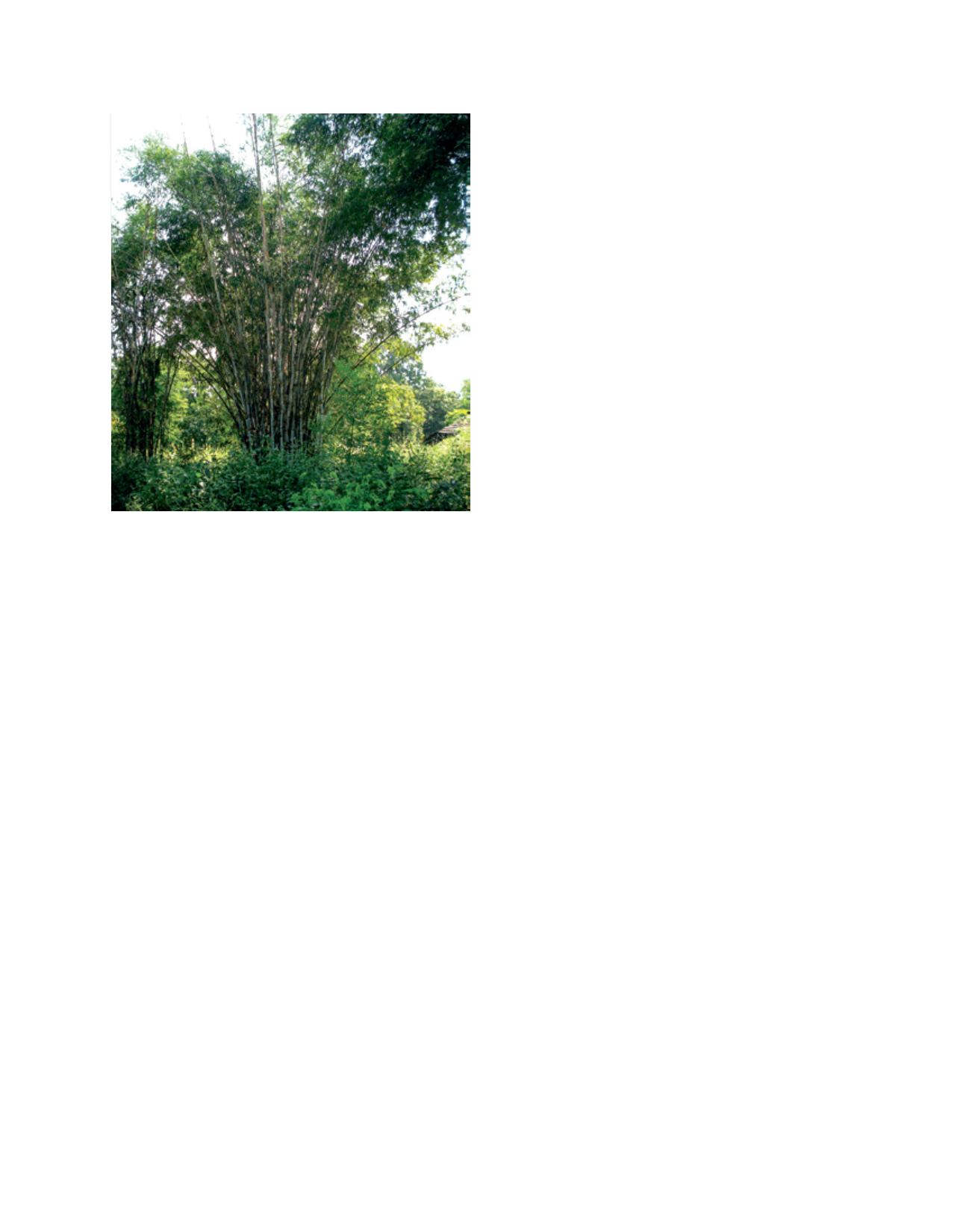

Bamboo in a homestead

Image: K. Rathna, CIBART

D

eep

R

oots