[

] 234

great challenges to get enough of the right food. Moreover,

although its vanilla is highly sought after over the world,

the majority of the 80,000 small-scale farmers who produce

the vanilla experience food insecurity, as they do not earn

sufficient income to adequately provide food for themselves

and their families. About 75 per cent of the small farmers

in Madagascar’s Sambava, Antalaha, Vohemar and Andapa

region – the majority of whom are vanilla farmers – live

on less than US$1 a day.

Vanilla is chiefly suitable for smallholder farmers and

family farmers. The average vanilla farmer owns 1 hectare

of land and uses traditional farming methods. The main

concerns that cause their income insecurity, and hence

their food insecurity, are fluctuating prices and margins.

The farmers therefore have very little power to advocate

a fair price and are cornered into a vulnerable position,

as a result of which their income is often insufficient and

unstable all year round. This weak bargaining power is due

to the fact that the pricing system is too complex for the

farmers to understand, and is largely unfair and not trans-

parent. As such, other players in the world market value

chain have the opportunity to benefit from their stronger

bargaining power, resulting in relatively higher prices and

margins for them.

Other issues affecting vanilla farmers include:

• Lack of resources – the farmers lack access to

information, technology and the financial resources

to build up savings and invest in insurance against

unexpected externalities.

• Poor quality product – desperate to sell their vanilla

to make ends meet, the farmers harvest their vanilla

too early or cure it too quickly, thus resulting in poor-

quality product.

• Theft – vanilla theft is quite high and is a huge issue

for these small farmers. Most farmers tend to harvest

their crops too early to avoid theft and therefore risk

producing poor-quality vanilla.

Recent research indicates that a handful of food and bever-

age multinationals and flavour houses are the most powerful

stakeholders in the Madagascar vanilla value chain. These

companies can and should help farmers to break out of the

cycle of poverty by ensuring that these smallholder farmers

are paid a fair price for their vanilla. A fair price covers,

among other things, a living wage for farmers, any other

labour either from family members or hired labourers, plus

all costs and risks involved in the production. Earning a fair

price will give farmers an opportunity to break out of the

poverty cycle and take better care of their families, invest in

insurance to recover from unexpected externalities, invest in

new and diverse crops, and have savings to fall back on. This

is the main topic companies should be focusing on in order

to ensure a fair system for these farmers and to contribute to

sustainable vanilla production.

Implementing viable sustainability standards, certifications

and corporate programmes – though not perfect – can be an

additional means to ensure progressive incomes for vanilla

farmers. In Uganda, it has been reported that organic and

fair trade certifications have helped about 1,200 producer

members of the Mubuku Vanilla Farmers Association to

improve their income situations.

We have seen that companies have made commitments

to improve livelihoods and increase yields through meas-

ures such as farmer training programmes, building schools,

providing financial assistance and health care. These projects

are supposedly impacting several thousands of farmers and

their families.

However, many of these programmes are a partial remedy

to the root cause of a lack of fair prices being paid to the

farmers. In addition to that, as there are about 80,000 small-

scale vanilla farmers in Madagascar, there is still a long way

to go. Moreover, the concrete impact this has had on the

livelihoods of the farmers is largely unknown and not well

measured. All in all, efforts from multinational brands and

flavour houses therefore need to be scaled up and improved to

show a demonstrable effect on farmers’ incomes from vanilla.

Support from African leaders and multilateral donor agen-

cies can also make a huge difference. In 2003, African leaders

adopted the Maputo Declaration,

3

promising to commit 10

per cent of their respective gross domestic product (GDP)

to agriculture and rural development. Improving agriculture

was seen as a path towards eradicating poverty and food

insecurity on the continent. Since 2003, only a handful of

African nations have reached or surpassed this target in any

given year.

4

Madagascar has not. The country has consist-

ently maintained a profile as one of Africa’s poorest nations.

Approximately 29 per cent of Madagascar’s GDP comes from

agriculture,

5

but seeing as this sector is largely dominated

by an extremely poor rural workforce that cultivates 1.3

hectares of family farms on average, and is plagued by mori-

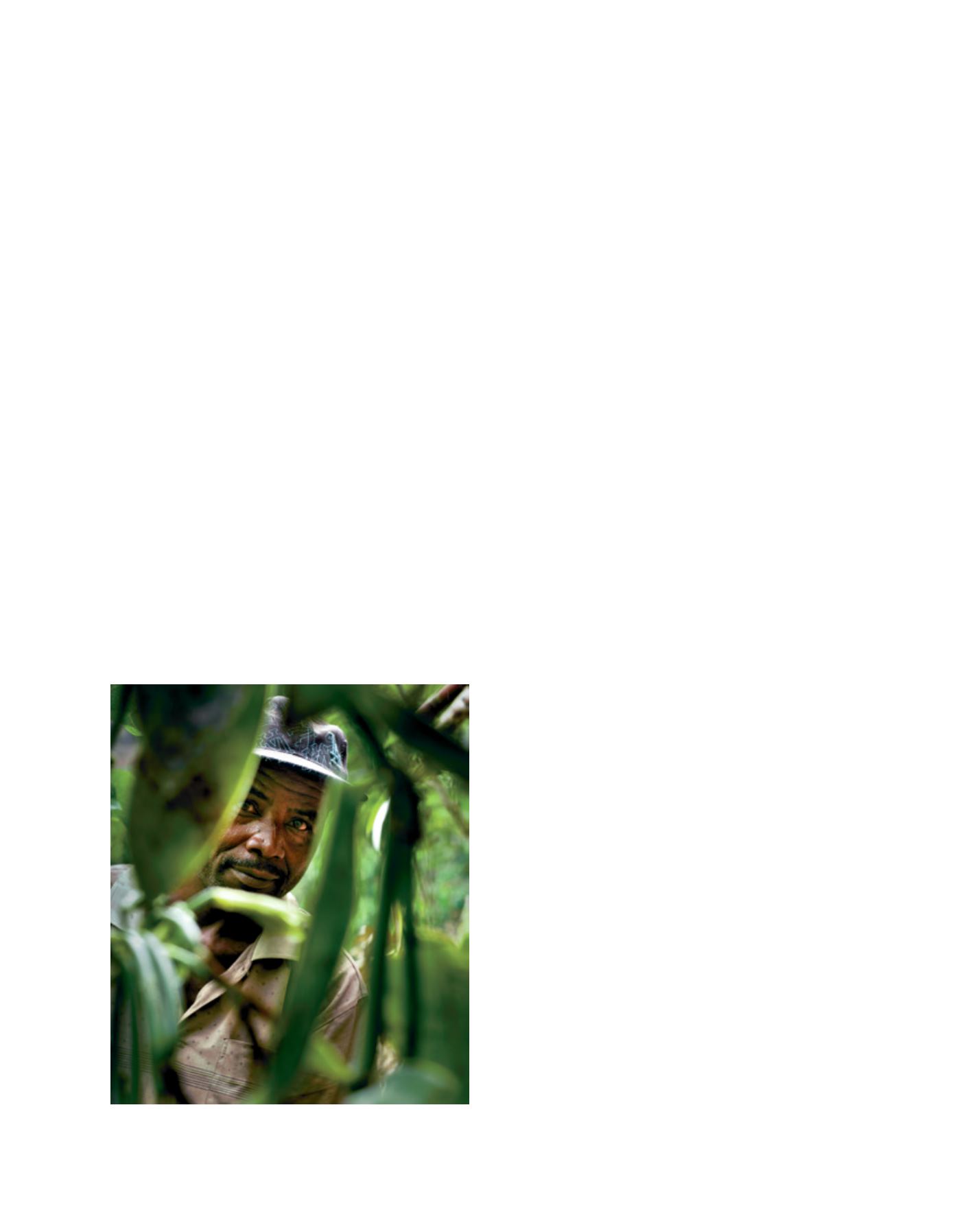

Vanilla is the world’s most popular flavouring, but most of Madagascar’s 80,000

small-scale vanilla farmers do not earn enough to feed their families

Image: Fairfood International

D

eep

R

oots