[

] 241

true, because family farming promises to create agricultural

practices that are highly productive, sustainable receptive,

responsive, innovative and dynamic. Given all these features,

family farming may strongly contribute to food security and

food sovereignty. It can also strengthen economic develop-

ment, creating employment and generating income. It offers

large parts of society attractive jobs and may contribute

considerably to the emancipation of downtrodden groups.

Family farming may also consistently contribute to the

maintenance of beautiful landscapes and biodiversity. For

food security to be a reality in the region, access to produc-

tive assets by family farmers should be prioritized. Family

farmer-led agricultural growth strategies must be grounded

within the context of prevailing asset distribution patterns.

Agricultural assets include physical assets (land, water and

labour), production assets (farm buildings, production

equipment and infrastructure), intangible assets or services

(marketing information, extension services), bulk infra-

structure (telecommunication, sewerage and electricity), and

production technology (seeds, plants and animal breeds).

The majority of family farmers in the region have limited

access to these assets; therefore they find it hard to actively

participate in the agricultural economy.

Access to productive assets in the region is driven by past

colonial policies and market forces of agro-industrialization.

Colonization and related oppressive regimes marginalized

indigenous communities’ ethnic minorities from owner-

ship and access of productive assets. The same economic

exclusion policies were also extended to other assets and

services such as water resources, extension and infrastruc-

ture. The dynamic of the agribusiness industry in the past

three decades, also known as agro-industrialization, has

also alienated family farmers in the input markets. These

corporate outfits have commoditized and commercialized

agricultural inputs, putting them out of reach for the major-

ity of the family farmers and smallholder farmers. Water and

land resource are still concentrated among few elite groups

with the majority of the population who are marginalized

from ownership and management of these resources. Many

countries have done little to redistribute these resources;

this is ironic given that most countries got independence

through liberation wars which were premised on redress-

ing skewed ownership of natural resources enacted by past

colonial governments.

Access to input markets and agricultural services such

as extension, bulk infrastructure and technology remains

a challenge for the majority of family farmers in the region.

The input markets in most countries are not well devel-

oped, and are characterized by the dominance of few

foreign multinational firms, poor price transmission, and

high transport costs due to distances between the rural

population and manufacturing sources. The input market

in most countries is also distorted by the dominance of

government and donor subsidy programmes. Extension

services in most countries operate below par with a high

extension-farmer ratio, hence delivery of technical and

marketing advice is compromised.

The region’s governments have been addressing these

issues using the industrial model of agriculture, while in

family farming the peasantry agriculture model is used and

this is called agroecology. Agroecology is very open to tech-

nological innovations but doesn’t over-emphasize them. It

rather puts emphasis on healthy soil, biodiversity and local

knowledge development as a basis for sustainable increases

in production. At the same time, it relates very strongly

to indigenous knowledge systems. Above all, agroecology

provides context-specific solutions rather than a ‘one-size-

fits-all’ approach.

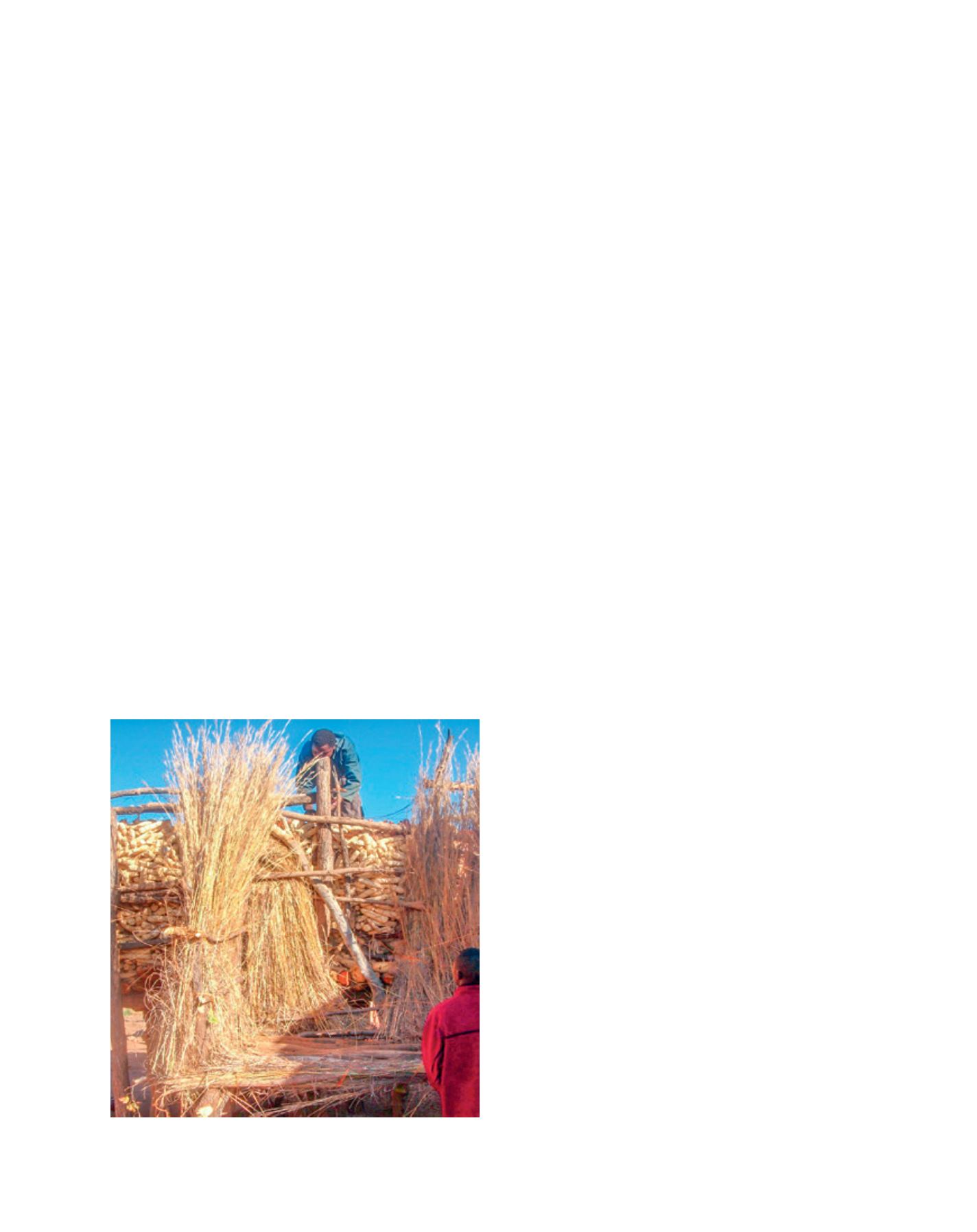

Family farmers by Zimsof, an ESAFF member

ESAFF is sharing an experience of family farmers in Zimbabwe

using the agroecology model of agriculture. The main cause of

food insecurity for many communal households in Zimbabwe

is their reliance upon a form of subsistence-based agriculture

which depends on a limited range of inputs often poorly

suited to local conditions.

Livelihood Insecurity in a Changing Environment: Organic

Conservation Agriculture is an initiative involving 791

resource-poor smallholder family farmers. It was undertaken

in 2011 as a partnership between three organizations: Garden

Africa, Fambidzanai Permaculture Centre and the Zimbabwe

Organic Producers and Promoters Association. Initially an 18

month action research project, it was extended to a further

two years, to end in 2015.

The project was founded on social and market research

which revealed a steadily growing domestic demand for organic

produce. Such demand was being serviced by imports from

South Africa while Zimbabwe’s resource-poor smallholder

farmers remain net recipients of food aid. The initiative therefore

sought to facilitate livelihood opportunities based on market

realities, while applying sound ecological management to restore

ecosystem functions for sustained productivity and growth.

A bumper maize harvest at Shashe after using organic compost

Images: ESAFF

D

eep

R

oots