[

] 242

Image: ESAFF

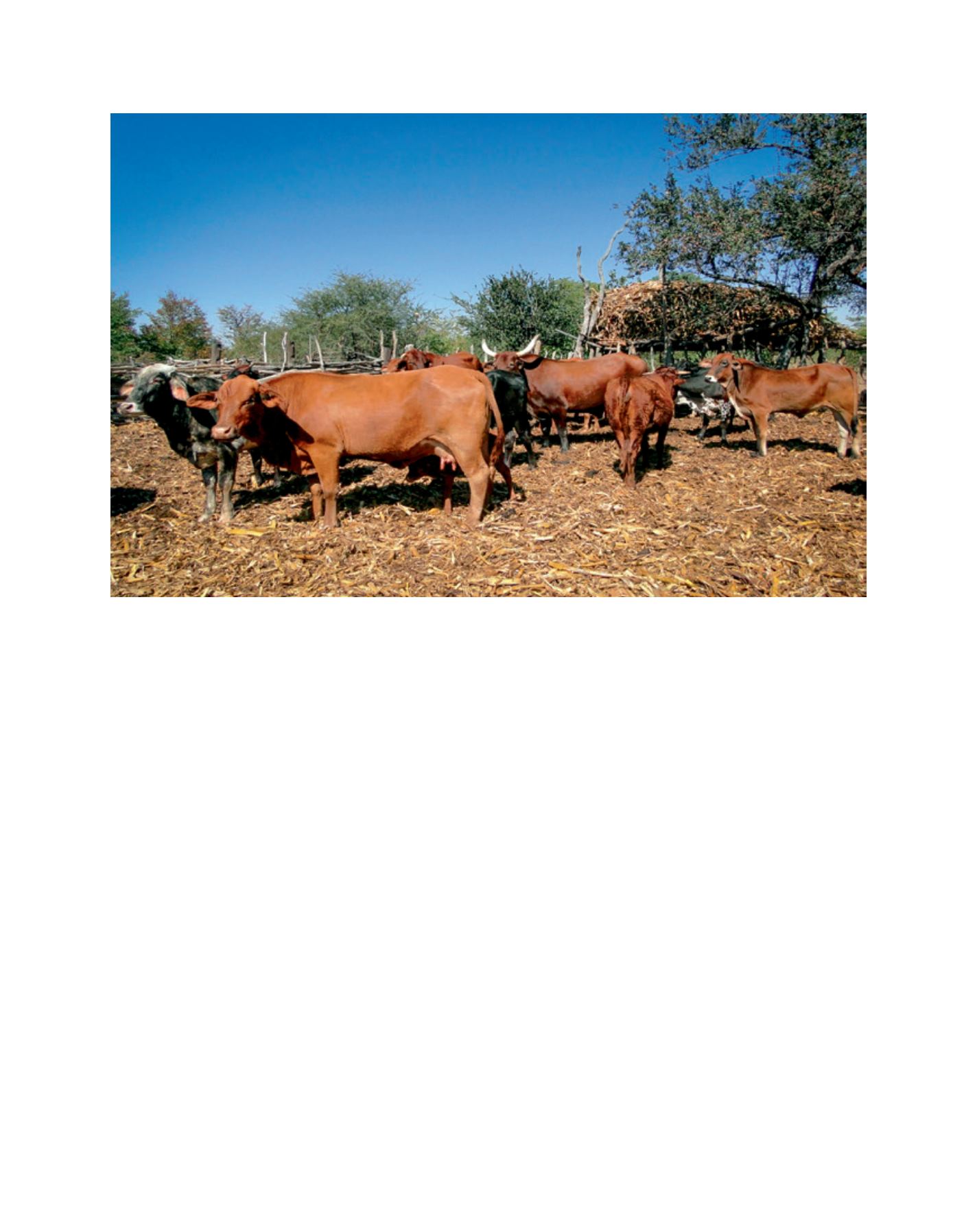

Animals’ droppings and urine on maize stoves are mixed as the animals step on it; in three months it will be transferred to the field as manure

The primary objective of this project has been to promote

a shift to agroecological farming. This involves rebuilding

soil organic matter and protecting it from further depletion,

and promoting a return to a productive diversity through

intercropping and rotation. By increasing biodiversity and

habitats, farmers are restoring the balance between pests

and natural predators and attracting pollinators to improve

yields. With market in mind, the second objective was to

explore opportunities presented by organic certification and

market development for Zimbabwe’s smallholder sector in

providing organic produce.

The project area is in nine districts of Mashonaland East

province, which ranges semi-arid to dry sun- humid, provid-

ing a strong empirical basis for testing permaculture methods

and the different strategies to be employed. The initial base-

line revealed that all farming households were producing at

below subsistence level, with extremely low levels of agrobio-

diversity, leaving them vulnerable to adverse ecological, social

and economic pressures. The level of farmers’ coordination

was low, affecting information sharing transacting costs and

collective action to address natural challenges, with food and

agricultural inputs regularly used as political tools.

This project is indicative of the situation in the whole

country. The average maize yield in Zimbabwe in 2012

was 83 kilograms per hectare, bearing in mind that the

US average is 10 tons per hectare. Having started at below

subsistence-level productivity, some of the project farmers

have since achieved the equivalent of 8 tons per hectare

using wholly organic methods. The word ‘equivalent’ is

used here because on their communal smallholdings of

between 1 and 1.5 hectares each, the farmers are encour-

aged to diversify their crops to include herbs, fruits and

vegetables, some for household consumption and some

for market. This is generally not considered in standard

measurements of farm output which focus on primary crop

yields only, so it remains invisible to national statistics.

The success of the project was measured through a series

of indicators such as relative increases in farm diversity,

yields and incomes of the initial 591 participating farmers.

Within the 18 months of the project, agrobiodiversity

had increased by 122 per cent, yields by 72 per cent, and

incomes by up to 90 per cent.

By the time the project entered its second phase a further 200

farmers had joined, either through new or existing associations.

Furthermore 3,562 more members were incorporated into the

national organic membership body, resulting in Zimbabwe’s

first 160 hectares of locally certified organic land with its

produce entering the domestic supply. After only 30 months,

the 40 associations, having begun at below subsistence produc-

tivity levels, had earned US$69,880 between them.

From the outset, it was clear that aligning the demands of

the market with sound ecological practices would be a deli-

cate balancing act. The emerging reality is that the market

is also demanding diversity. Central to this project has been

facilitating the generation and transfer of knowledge, skills

and confidence to harness the potential of natural and social

D

eep

R

oots