[

] 80

and porcupines in the mountains. This loss has become

so intense that in some places the community has either

left farming or grown forest trees on their piece of land.

The age-old practice of biofencing, which was designed to

protect against wild animals, has been lost in the course of

time. Biofencing used different types of shrubs which had

qualities to prevent intrusion into farm land. Biofencing

served multiple purposes in villages – as well as providing

fencing, the shrubs produced various fruits, or had medici-

nal and fuel values.

Himalaya represents a true family farming model, through

the collective efforts of community where families help and

seek support from one another. There is an arrangement

for material, labour and the sharing of produce. Landless

farmers and artisans also help farmers as payment for

grains. Family farming here is a multi-stakeholder affair,

where all community members work collectively but main-

tain individuality too.

Mountain agriculture cannot be treated in isolation.

Various factors contribute to growth here. Agriculture is

not possible without the forest, as various inputs come

from there. Cultivated land is a deposition of soil that

comes with rainwater from the forested top of the moun-

tain. Local cattle play their role in ploughing, threshing and

other purposes, and these animals depend largely on the

forest for fodder. Forest litter also becomes a major source

of compost for the family farm. The litter is spread as a bed

under cattle and, when mixed with their waste, helps to

prepare the manure.

In the past, the nutritional needs of the mountain commu-

nity were met by traditional family farming. The nature

of local crops is such that it matches the local commu-

nity’s physiological needs. Millets were major crops in the

mountains, and these served all basic bodily needs. For

example, in high altitude areas, buckwheat protects against

solar radiation hazards because it contains a compound

called rutin. There are several such relationships between

climatic produce and local human needs, and this age-old

nutritional dependence is peculiar to Himalaya.

Millets were the staple diet, with other elements coming

from cereals, vegetables and fruits. One special contribu-

tion used to come from wild fruits and vegetables, serving

the requirement for micronutrients and essential elements.

There was a striking sustainability between human needs

and the region’s climatic regime. This sustainability broke

as we advanced in status and knowledge. Paddy and wheat

were assumed to be elite class food, and that discouraged

millet consumption at village level too. Besides, the Indian

Forest Act prevented communities from having access to

forest the resources they contain. The third factor that

ruptured the local farmers’ relationship was market inva-

sion. Community dependence on the market began to

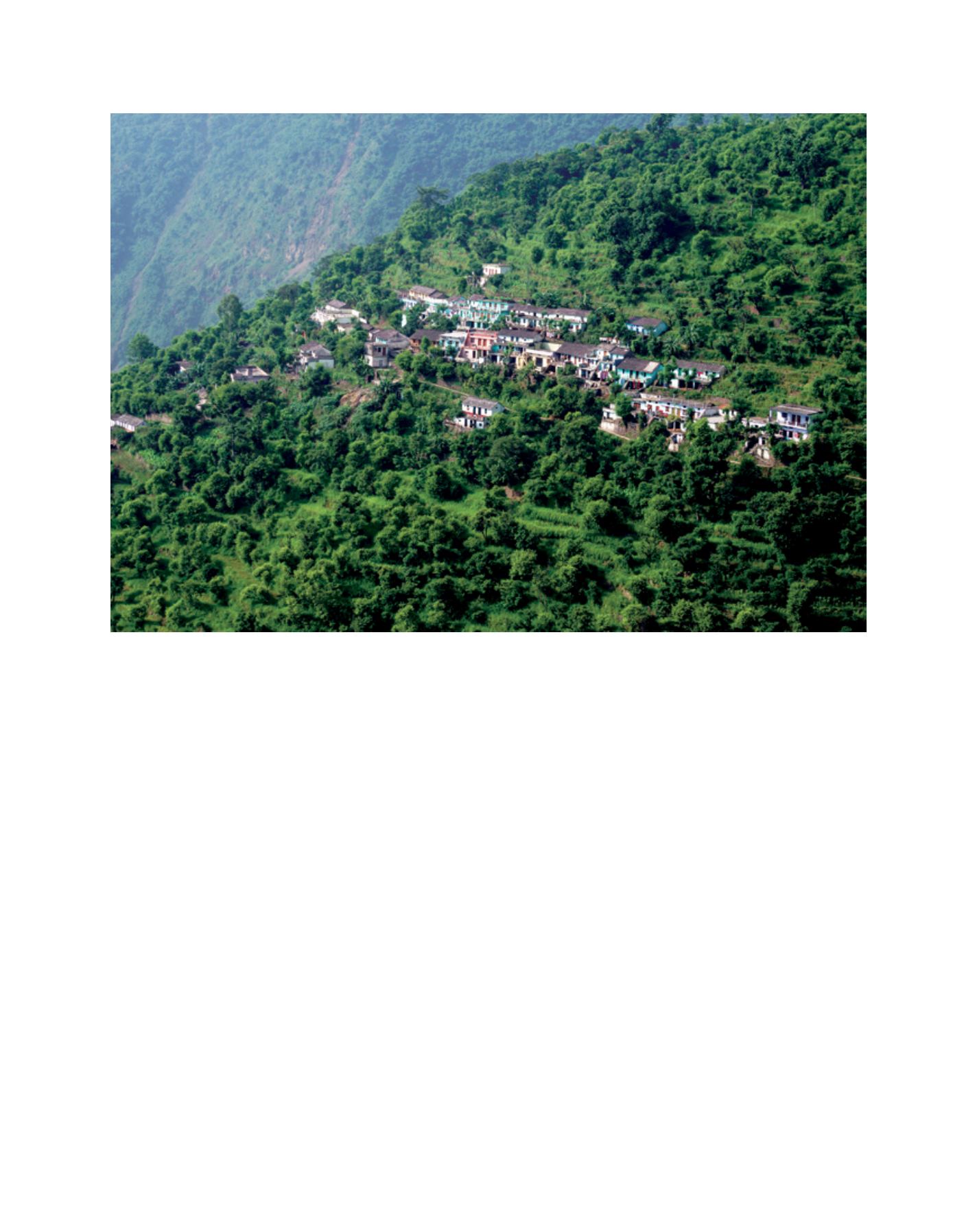

Himalaya represents a true family farming model in which communities work together and families support one another

Image: HESCO

D

eep

R

oots