[

] 136

many ways and resource planners have to perform a

demanding balancing act to ensure economic, social

and environmental sustainability at local, regional and

national level.

A case study in Swedish Lapland illustrates the

challenges faced by various users of the same forest

resource for different purposes. Malå municipality

is located in the county of Västerbotten in Northern

Sweden. Forestry is one of the basic industries for

the development of society in this area and is thriv-

ing, together with electric power plants, a mining

industry, car testing, tourism and outdoor recrea-

tion. Alongside these activities, reindeer husbandry

has been present in the area for centuries. This places

competing demands on forest resources – as well as

the demand for timber, local indigenous Sámi rein-

deer herders need mature forests with winter lichen

in the winter grazing pastures for their animals, while

summer grazing areas need to provide food and cover

when the calves are still young.

Using the innovative Tool for Sustainability Impact

Assessment (ToSIA), the project was able to assess

contributions to local employment from both sectors

through their activities, influences on cross-sector

production costs, carbon sequestration and forest

growing stock. These assessments aimed to find out

what impacts different forest management practices

understand the wider consequences of their choices by illustrating

the different impacts different development scenarios can make. In

order to cover different aspects in a balanced way, each of the above-

mentioned dimensions matters.

Environmental sustainability in relation to forests, for example,

can be assessed with indicators like the amount of decaying wood,

the area of forests for remaining biodiversity use and production of

energy and greenhouse gas emissions from wood chips or timber.

The economic aspects can be assessed with indicators like local

added value and the production costs of wood-based products.

Employment and wages are typical indicators for social sustainabil-

ity but there are other possibilities too: for example, the number

of hunters, hikers or berry pickers to describe the importance of

recreation or the number of occupational accidents to show the level

of occupational health and safety. Comprehensive indicators like

carbon and water footprints can also be used when they can be

determined for a product.

All these indicators help planners and decision makers to study

how changes in the forest-based sector have an effect on different

aspects of sustainability – and how, in the end, they affect people.

For example, the Northern ToSIA project,

1

which assessed the

sustainability of forest-based activities in various northerly regions

as part of the EU’s Northern Periphery Programme, used different

sets of indicators to assess the impacts of alternative decisions in

forestry and regional development on forest wood-based chains.

These included tourism, the bioenergy sector and indigenous Sámi

reindeer husbandry livelihoods. The region’s forests are used in

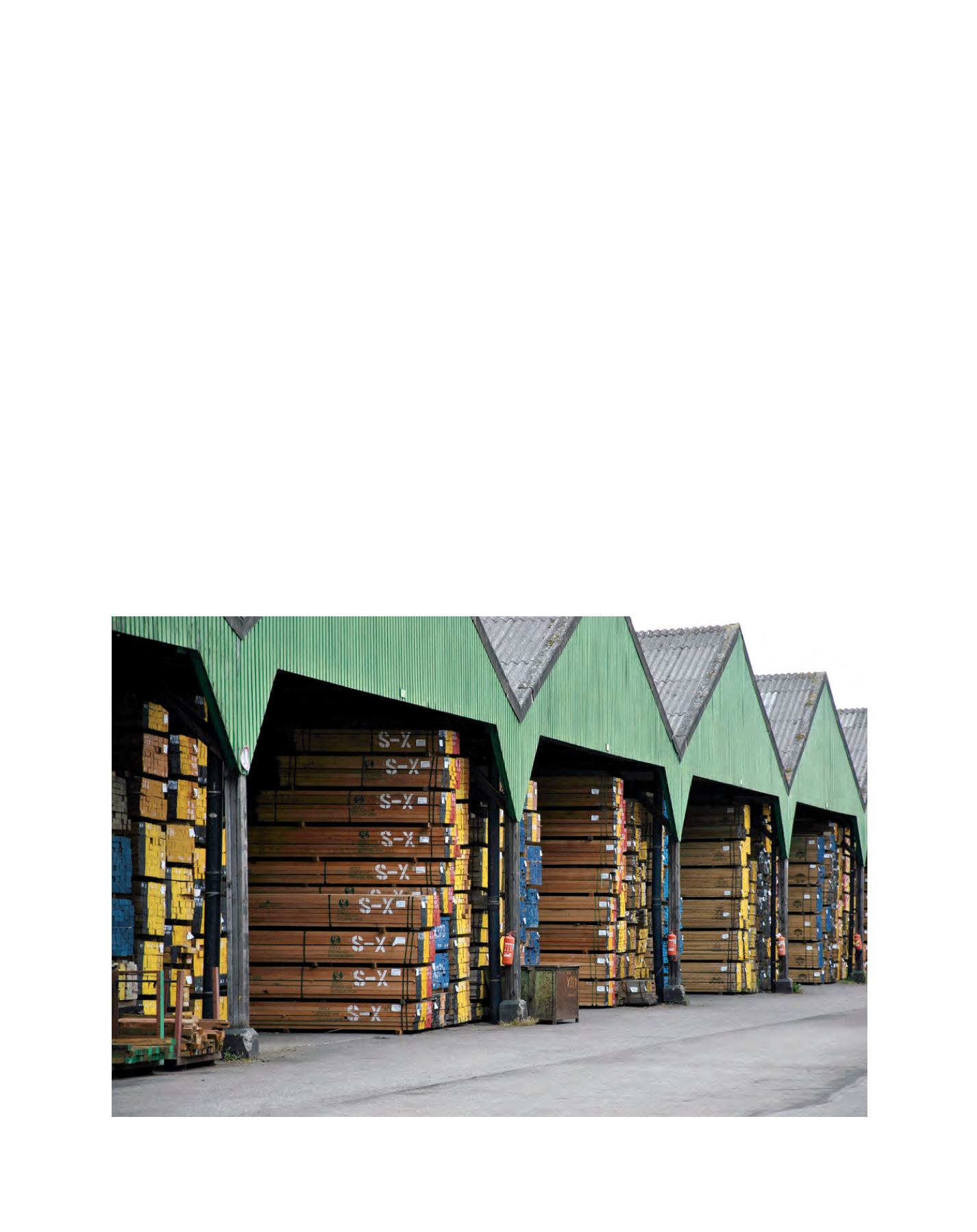

Decisions affecting the forestry sector can have an impact a long way down the chain

Image: EFI