[

] 170

tive has allowed Model Forest experts from Canada to

put tools and methodologies in place that will improve

forest management in Argentina’s national network,

and provide an opening for further extension in the

Ibero-American Model Forest Network.

Lessons learned

A Model Forest directly addresses the very challenging

social aspect of the sustainability equation. It initi-

ates and sustains a robust exploration of the collective

demands that we place on our ecosystems, the trade-offs

that these demands involve, and options for designing

a sustainable future. Model Forests are about a shared

investment (human, financial, intellectual, political)

in finding effective, long-term solutions to shared

challenges. The approach also has its limitations. For

example, it cannot work in places where participants

are unwilling to listen openly to each other, where the

process is largely driven by a single organization, or

where persistent and significant funding challenges

exist. However, the overwhelming majority of Model

Forests have succeeded, and continue to do so.

Twenty years of experimenting with Model Forests has

taught us that delivery of SFM policy must be shared

with the people who will live with the results. Meaningful

engagement of local stakeholders is a prerequisite to

sustaining buy-in, momentum, direction and support,

and sustainable management of natural resources must

provide an economic dividend to local stakeholders.

We have also learned that national forest and other

resource-focused agencies are key enablers as well as

beneficiaries and partners, and that there is high value

in working at a large physical scale and across disci-

plines and administrative boundaries. Donors, managers

and policymakers need to increase their tolerance for

innovative approaches and recognize that building a

sustainable future is a long-term process, not a project.

The case studies in this chapter are linked through the

six Model Forest principles, which are flexible enough to

be adapted to almost any context and landscape. Lessons

learned are then shared through the IMFN and more

broadly to accelerate progress towards sustainability goals.

Model Forests demonstrate that small-scale solutions

to large national- or international-level concerns can

make a difference. Issues such as transnational resource

management, poverty alleviation and climate change

provide opportunity for increased collaboration among

IMFN members, as well as with other organizations with

similar goals.

Next year will mark the 20th anniversary of Canada’s

announcement of the IMFN at the 1992 UNCED

Summit. The message we carry forward as we look to

the next two decades is firmly rooted in a view that the

array of challenges Model Forests address are not devel-

oped or developing country issues; they are familiar in

all our landscapes. However, both the range of issues

considered and the options for addressing them are

substantially enriched through meaningful, broad-based

partnerships such as those found in Model Forests.

address the sustainability of watershed resources and allowed them

to express their own views and priorities.

In Samar, as elsewhere, stakeholders are motivated by the expecta-

tion that better management will lead to higher incomes and better

opportunities for their families and communities. In Samar, this

took the form of almaciga resin collection, coconut coir production

and rattan processing, while resource base improvement through

agroforestry and development of multi-purpose crops and ecotour-

ism activities motivated stakeholders to participate.

Sharing best practices internationally

Networking and knowledge sharing between sites is a key Model

Forest principle and motivator for joining the IMFN. Over the

years, Canada’s Model Forests have been particularly successful in

sharing experiences internationally. For example, Canada’s Prince

Albert Model Forest is collaborating with Chile’s Araucarias del Alto

Malleco Model Forest and Vilhelmina Model Forest in Sweden in the

IMFN’s first tri-continental agreement to share knowledge and experi-

ences between indigenous stakeholders. The Manitoba Model Forest

recently concluded a three-year project with the Reventazón Model

Forest, Costa Rica, where an ecotourism business was developed

in collaboration with the Cabécar indigenous people; and Canada’s

Lac-Saint-Jean Model Forest is working with carpenters in Dja et

Mpomo Model Forest, Cameroon, on establishing small enterprises

turning exotic wood residues into marketable products such as pens.

Since 2007, the Government of Canada, the Canadian Model Forest

Network and the Argentinean National Model Forest Network have

been working together to transfer Canadian expertise to Argentina

in the development of criteria and indicators (C&I) for SFM. A suite

of local level indicators based on Canada’s national C&I framework,

designed to monitor progress towards sustainability, was developed

in each of Canada’s Model Forests in the late 1990s to enable stake-

holders to track changes and trends in the condition of forests and

in the economic and social benefits we derive from them. This initia-

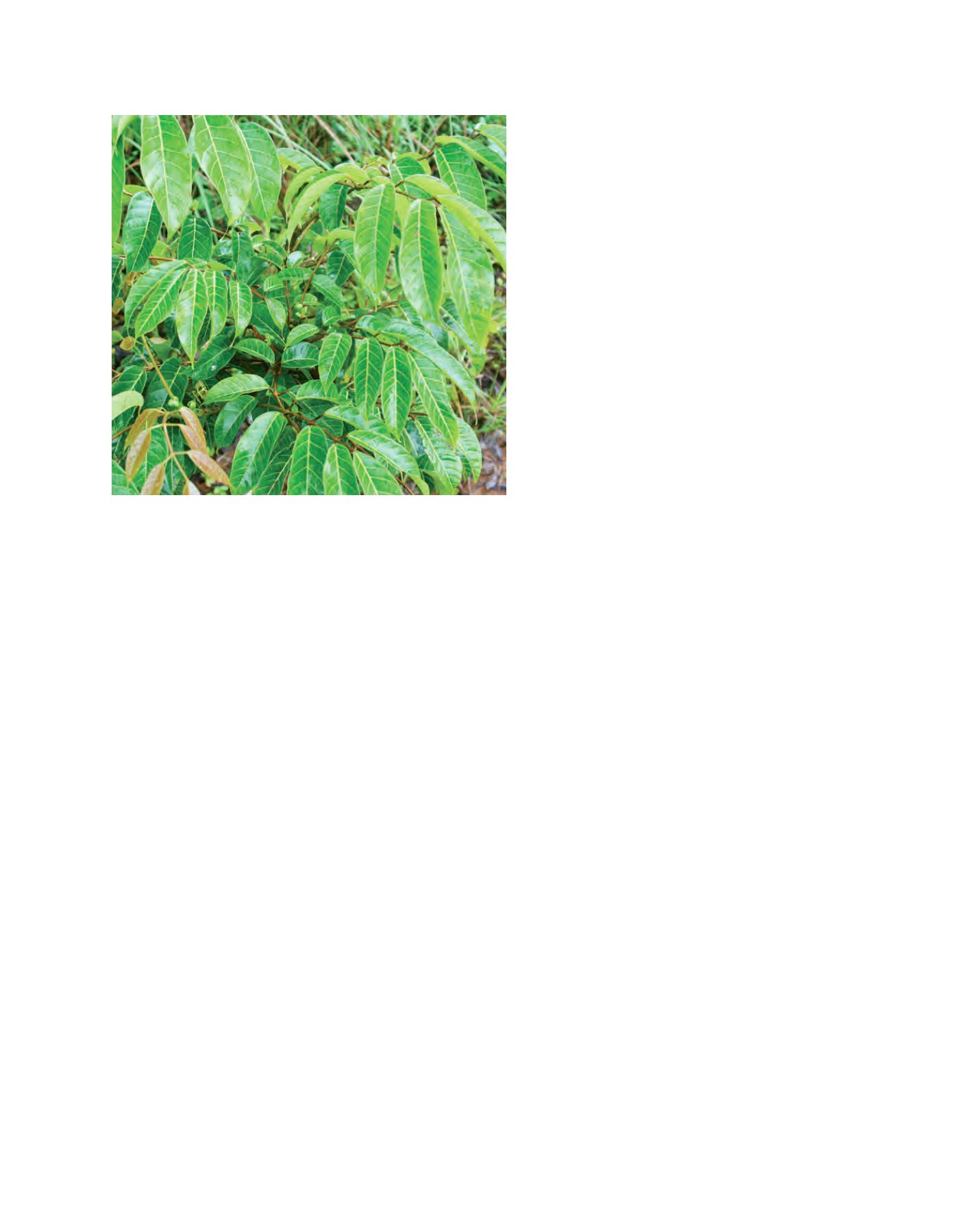

Pili tree, Ulot Watershed Model Forest, Philippines

Image: The International Model Forest Network Secretariat