[

] 229

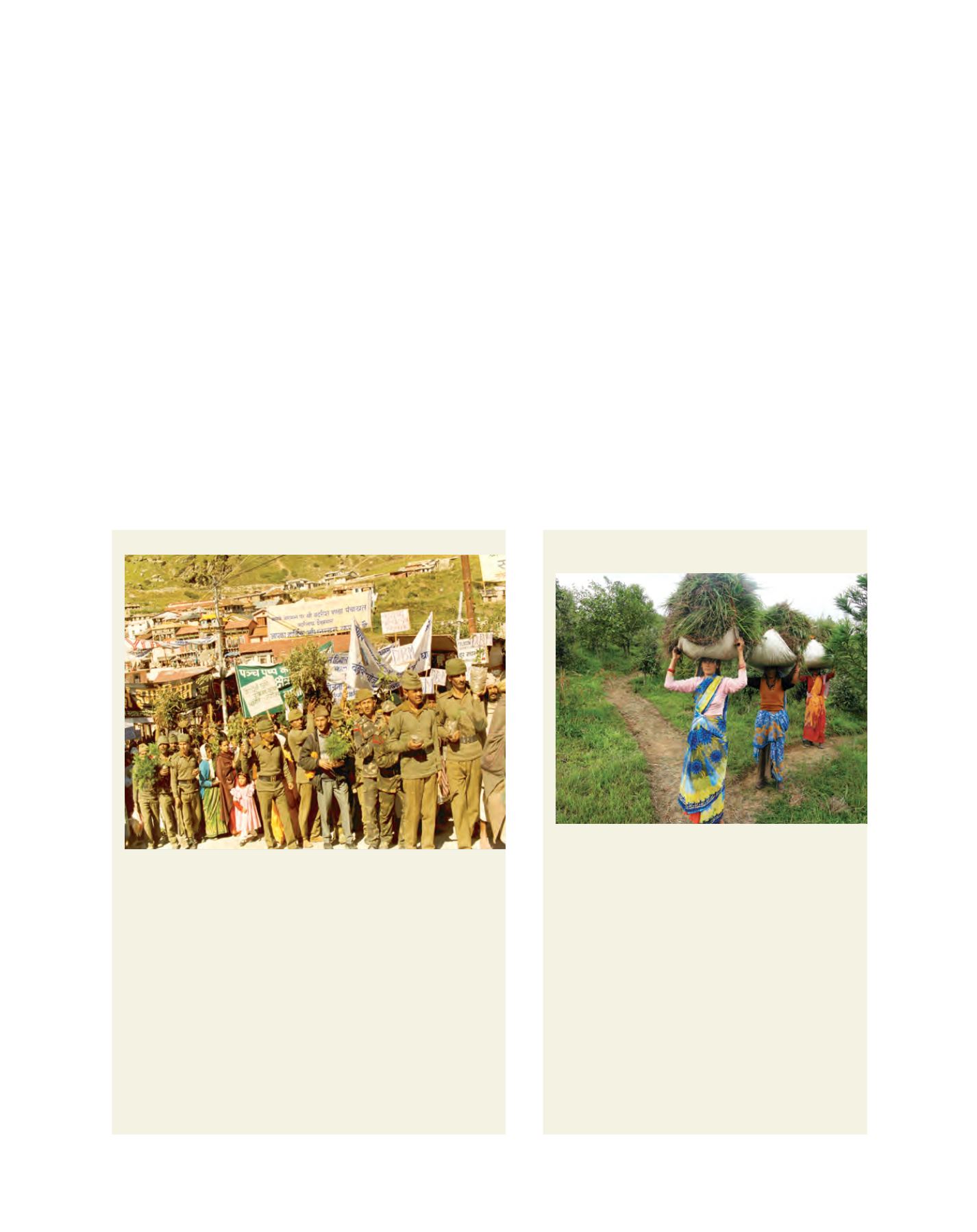

Planting the forest of Rakshavan by the Indian army

Establishment of a sacred forest by local

communities at Kolidhaik

The Indian army traditionally plants trees in high altitude areas, to

provide cover during operations, as a natural source of oxygen and to

relieve snow blindness in winter. The Badrinath reforestation programme

inspired the army to launch a similar initiative in Badrinath. The Garhwal

Scouts regiment carried out a project between 1998 and 2000 to

establish Rakshavan (a defence forest) on degraded defence land at

Dhantoli.

Army personnel promoted environmental awareness among the

locals, pilgrims and villagers of eight adjacent villages of Badrinath and

organized tree planting ceremonies.

A 10 hectare plantation site was developed at Dhantoli and almost

16,697 well-established and hardened saplings of various high-altitude

trees and shrubs were planted at the Rakshavan site. Out of these,

15,299 saplings of 11 high-altitude trees and shrubs were found to have

survived at the project site up to the date of completion of the project. In

addition, the army established a nursery of high-altitude trees and shrubs

within the plantation site. The army used seedlings raised and hardened

at the nursery for subsequent plantations. Several similar projects have

followed under the auspices of the Indian army in various locations.

Important lessons learned during the Badrivan restoration

programme at Badrinath led to a follow-up action

programme to create a forest for eco-restoration and

biodiversity conservation. The Sacred Forest Programme

(SFP) was executed at Kolidhaik village in the Kumaun

region of Uttarakhand between 2004 and 2007 with the

participation of local communities.

The programme addressed the need to reforest

community lands in and around the village at an altitude

of 1,740 metres. It was necessary to obtain the blessing of

both the imam of the mosque and the priest of the temple

in the village, both of whom agreed to become involved in

the project to undertake ritual plantings of around 8,000

tree seedlings.

Villagers from both religious groups responded

enthusiastically to the establishment of the sacred forest as

an act of devotion. A total of 6,200 seedlings of about 20

promising tree species had survived up to May 2007. The

forest was dedicated to Kail Bakriya (the local deity) and

felling of trees was banned, with the exception of fodder

collection for local families.

occurred in modern times with the Chipko movement for the preser-

vation of India’s forests, which in 1976 forced the Government to ban

commercial felling of green trees above an altitude of 1,000 metres.

Vegetation forms a green ‘security blanket’, protecting the fertile

yet fragile soil, maintaining balance in atmospheric conditions,

safeguarding supplies of fresh water and moderating their flow

to prevent flood and drought. The green cover, especially in our

forests, is under attack by the greed of the rich and the need of the

poor. This must be corrected

5

. As far back as 22 centuries ago, the

Emperor Ashoka defined a king’s duty as not merely protection of

citizens and punishment of wrongdoers but also, preservation of

animal life and forest trees. Along with the rest of mankind, we in

India – in spite of Ashoka – have been guilty of wanton disregard

for the sources of our sustenance

6

.

In Indian culture, trees have come to symbolize eternity, constancy

and unity of nature. Sages in India have long believed that gods

descend from heaven to Earth through the trees to communicate

with human beings. One of the old scriptures states: “The supreme

one infuses energy into the peaks of trees. Therefrom rays radiate

outwards from descending layered limbs. May they reside within us”.

7

Meditation traditionally took place while sitting under a tree against

its trunk as if to physically support a spiritual connection leading to

personal transformation. When we hear the story of the

forests we hear the voices of the future

8

.

Forests are also traditional sources of food, fuel,

fodder, fertilizer and fibre (the 5 essential ‘Fs’ for Chipko)

and forestry practices should improve the lives of forest

dwellers, whether human or other species. The reckless

exploitation of nature and especially of forests must there-

fore end. There is an urgent need to evolve programmes

through which forests can not only coexist but be

enlarged side by side with active community participa-

tion. The case studies that follow are based on the ethos

‘let us give back to Nature what we have taken from it

– creativity and capacity for renewal’. They illustrate the

merits of deploying an appropriate driving force, whether

spiritual, religious, traditional or customary practice, to

encourage the planting of trees, symbolizing our faith in

the future. Let this act of faith (and investment) in the

future grow, particularly during this International Year

of Forests, 2011, inspiring change, enhancing value and

securing our own future. The ‘Katoupanishads’ exhorts

us ‘to arise and awake and walk boldly across the razor

sharp path ahead’.