[

] 259

Forests and people in the United States

Thomas L. Tidwell, Chief of the US Forest Service, US Department of Agriculture

A

merica’s forests tell a story of change. The forests first

encountered by wanderers from Asia about 15,000 years

ago were nothing like today. Many species of plants and

animals are now extinct, and as trees and other plants advanced

before the retreating Pleistocene glaciers, they gradually created

the forest mosaics familiar today. Ponderosa pine, for example,

now common across the Western United States, arrived in some

locations only about 2,000 years ago.

Early human impacts

Aboriginal peoples cleared land for agriculture, cut timber for housing,

maintained canebrakes and shrubfields for basketry and cultivated

oak, walnut, hickory, chestnut, blueberry and other plants. They used

fire to create and maintain prairie and open woodland for hunting

and other purposes. By the 1600s, they were connected to European

fur markets, contributing to great wars and population shifts; on the

Great Plains, they tamed feral horses from Spain, created nomadic

cultures around bison and used fire to stimulate forage.

The Europeans brought diseases that ravaged tribal

peoples. Entire regions were depopulated by the effects of

war and disease, allowing forest succession in places where

it had been checked by aboriginal fire. American Indian

fire use was suppressed in some places but mimicked in

others for resource benefits, such as maintaining forage

and mast nuts for cattle and pigs. Settlers also brought fire

to landscapes where it had once been rare.

Frontier fire was connected to deforestation. As settle-

ments expanded, the United States lost much of its original

forest estate. In 1607, when the English first settled in

Virginia, about half of what would become the United

States was forested; by 1907, it was about a third. Roughly

100 million hectares of forest were lost, and nearly two

thirds of that loss came in the second half of the 19th

century due to forest clearing for timber and agriculture.

The damage was mainly east of the Mississippi River – but

now it threatened the West as well.

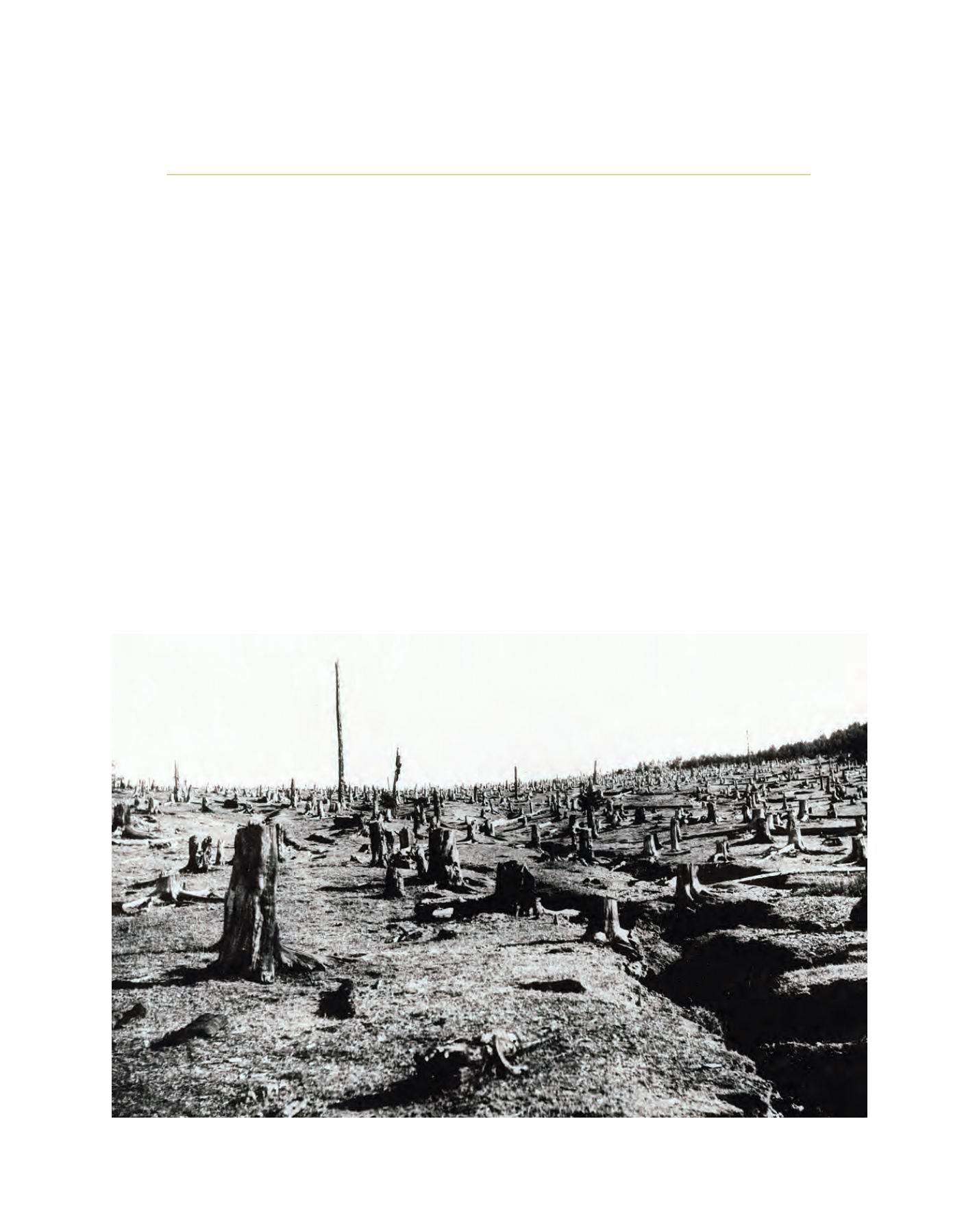

Privately logged timberland near Leadville, Colorado showing erosion due to deforestation. This area later became part of the San Isabel National Forest, Colorado

Image: USDA Forest Service