[

] 257

This has allowed us to deliver custom-made responses

that deal with the specificities of each of the diverse

landscapes.

Saving forests, saving water

To mention just one of many examples, in China, we

have been working in the Miyun watershed, which

supplies up to 80 per cent of the freshwater used in

Beijing. Worsening water shortages in Beijing have been

directly linked to the disappearance and degradation

of much of the original forest in the watershed. When

this was first recognized, the Government attempted to

resolve the problems by imposing a strict logging quota

but the forest quality and water supply continued to be

less than ideal.

The LLS project initiated by IUCN worked with local

authorities and communities to introduce a more inte-

grated form of landscape management and restoration,

which recognized the multiple needs and functions of

the watershed and brought together the many differ-

ent stakeholders. This included piloting a partial lifting

of the logging quota. The introduction of a new set of

forest management practices represented a shift from

a strict protective approach, towards more sustainable

resource use through active management by forest-

based communities.

This has resulted in a formal agreement that recog-

nizes different forest management and forest use

regimes, merging the technical information held by

companies to take on the challenge of forest landscape restora-

tion. This concluded with an extremely significant outcome: a

joint commitment to restore 150 million hectares of deforested

and degraded landscapes by 2020. That is approximately equiva-

lent to an area the size of Mongolia, with phenomenal benefits to

biodiversity and livelihoods.

IUCN has estimated that restoration on that scale will be worth

US$85 billion per year to local and national economies. Highlighting

the worth of ecosystems and the services they provide in this way

has also been a part of other work IUCN has been doing to come

to a better understanding of the value of forests at each level of the

global economy.

One such programme of work in this regard, which has also

generated valuable new knowledge on the spatial variance of poverty

and forest dependence in forest-adjacent communities, has been our

Landscapes and Livelihoods Strategy (LLS).

1

Already in place for

five years and ending its first phase in 2011, LLS has been improv-

ing sustainable management of natural resources – and the lives of

people who depend on them – in more than 20 countries across

Africa, Asia and Latin America.

On a global level, we have learned from LLS that the direct

benefits from forests are worth around US$130 billion every

year: roughly equivalent to annual official development assist-

ance worldwide. We have also discovered that forest reliance

globally varies between about 25 per cent and 40 per cent of total

annual income.

LLS builds on the ecosystem approach in taking a ‘landscape’

view, which allows us to look at and manage forests as part of a

broader and more complex ecological and socio-economic system.

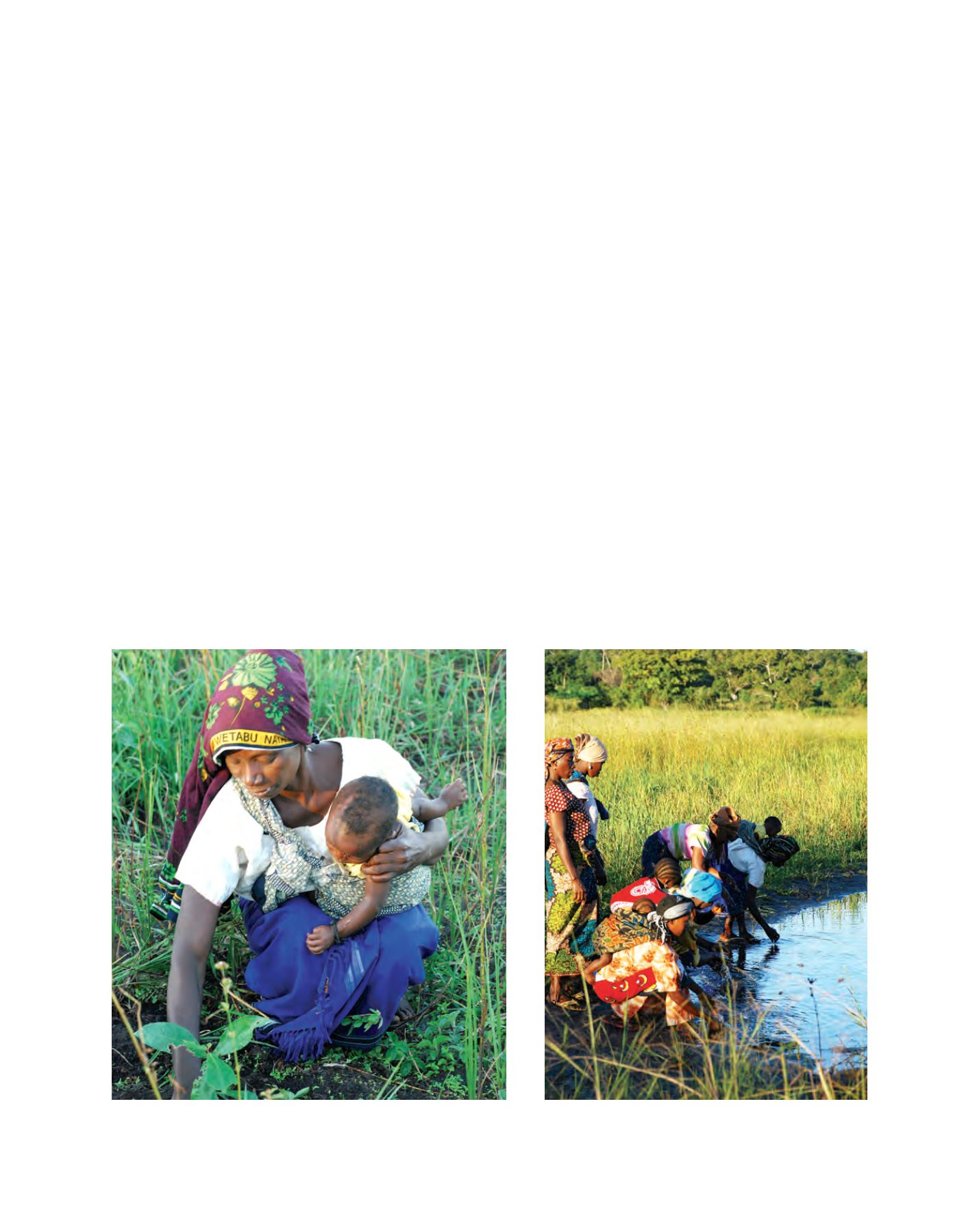

Mother and baby planting seedling to restore forested area near precious water

sources, Tanzania

Women drinking at water source in forest landscape, Tanzania.

Safe water supplies result from forest protection

Image: IUCN/Daniel Shaw

Image: IUCN/Daniel Shaw