[

] 22

W

ater

D

iplomacy

biodiversity benefits generated by reduced water pollution, micro-

economic impacts of improved water allocation (for example, for

agricultural productivity) and economic gains from the development

of large infrastructure for water storage, flood control or hydropower

generation. Some of these benefits are manifest as reduced costs of

water supply and power generation, or as reduced risks arising from

floods, droughts and disease. Other benefits of cooperation are less

well known – such as those related to reduced political tensions

(ultimately leading to reduced defence spending), opening opportu-

nities for cooperation in other areas (such as trade liberalization) or

the macroeconomic impacts of improved water management facili-

tated by cooperation.

On one hand, it is clear that there are significant benefits from

cooperation. On the other, when countries fail to cooperate and

instead compete for use of the water resource, the costs can be high.

Aquifers draw down due to competing pumping, crops die as flows

dip in the growing season and the land floods as water is released

in the winter, ice flows disrupt navigation and power generation,

polluted waters impact on the health of downstream communities

and raise the costs of drinking water supply, reservoirs are silted up

by sediments, and so on. Transboundary cooperation, based on the

Helsinki and New York conventions, can help to prevent such costs.

Besides providing information on the benefits of cooperation

internationally, water management – both nationally and in the trans-

boundary context – needs intersectoral cooperation. A particularly

successful approach to fostering the sort of intersectoral coopera-

tion that forms an essential foundation for better water management

is embodied by the national policy dialogues on integrated water

resources management and water supply and sanitation, being held

within the European Union Water Initiative. UNECE – focusing on

water sector reforms to achieve integrated water resources manage-

ment – is working with the Organization for Economic Cooperation

and Development – which is focusing more on economic and finan-

cial analyses – to implement these dialogues in nine

countries across Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and

Central Asia. The objective of each policy dialogue is

to facilitate the reform of water policies in a particu-

lar country or region. Each policy dialogue involves

high-level representatives of all key partners, including

national and basin authorities, representatives of relevant

international organizations, civil society (non-govern-

mental organizations) and the private sector.

The national policy dialogues have also provided a

forum for discussions on the setting of national targets

relating to safe drinking water and adequate sanitation,

the subject of the Helsinki Convention’s Protocol on

Water and Health. The protocol, adopted and signed

by 35 states in London in 1999, now has 26 contracting

parties in the UNECE region. Each party has to set, and

subsequently implement, targets in 20 areas covering

the entire water cycle. For example, in relation to sani-

tation, target areas cover access to sanitation, the level

of performance of sanitation systems, the application of

recognized good practices to the management of sanita-

tion, and the disposal and reuse of sewage sludge from

sanitation systems.

The process of target setting is flexible and adaptable

to specific national conditions. Thus, the parties appre-

ciate the target setting and reporting process as a useful

policymaking and planning tool that enhances intersec-

toral cooperation – which is where the national policy

dialogue helps – and assists governments to express

clearly and transparently their priorities in progressing

towards universal access to safe water and sanitation.

Both globally and in the UNECE region, advances in

access to water and sanitation are being made. But safe

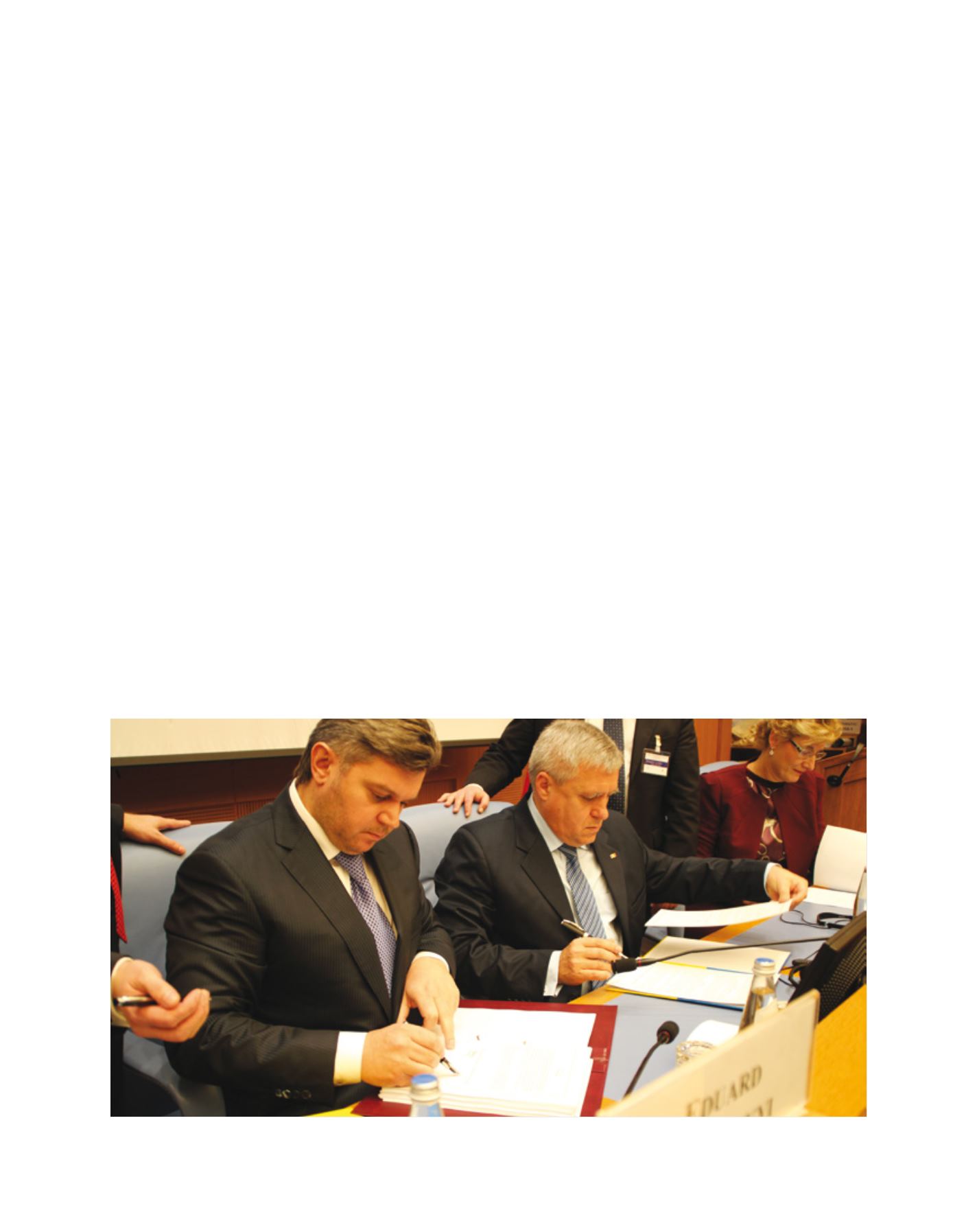

The signing of the Treaty on the Dniester River Basin in Rome in 2012

Image: UNECE