[

] 26

W

ater

D

iplomacy

Water diplomacy in practice

BRIDGE operates in six basins in Latin America – three in

Mesoamerica and three in the Andes in South America – and three

sub-basins in South-East Asia. In Mesoamerica BRIDGE has demon-

stration projects in the Coatan (Guatemala-Mexico), Goascorán

(Honduras-El Salvador) and Sixaola (Costa Rica-Panama) basins. In

the Andes, BRIDGE project sites are in the Zarumilla (Peru-Ecuador),

Catamayo-Chira (Peru-Ecuador) and Titicaca (Peru-Bolivia) basins.

While the basins have distinct differences within and across regions,

there are key strategic similarities in how water diplomacy works

across all of the project’s transboundary basins. BRIDGE also oper-

ates in South-East Asia on three transboundary tributaries of the

Mekong River: the Sekong (Viet Nam-Lao People’s Democratic

Republic (PDR)-Cambodia), the Sre Pok (Viet Nam-Cambodia),

and the Sesan (Viet Nam-Cambodia).

BRIDGE has been particularly active in Latin America. In the

Goascorán basin shared between Honduras and El Salvador, IUCN

has worked with partners and stakeholders to revitalize a basin

management group responsible for joint planning and manage-

ment, constituting a major step forward in cooperation between

the two countries. Key to the success of this effort was the inclusion

of stakeholder groups in the planning body – greatly

increasing its legitimacy, status and footprint by

including local development agencies, national level

ministries and private actors. Through these actions,

BRIDGE provided essential support for the formation

of a new transboundary committee which aims to

develop the financial and institutional model for the

basin – ensuring that the institutional arrangement

is sustainable long-term. This is a powerful example

of how strengthening stakeholder participation can

transform weak institutions into legitimate bodies of

governance while enhancing cooperation in a trans-

boundary context.

Similarly, efforts to increase cooperation and

improve water governance capacity in the Sixaola

basin are paying off. The basin is shared by Panama

and Costa Rica, and the Permanent Binational

Commission has managed cross-border relations

between the two countries for some time. However,

technical and legal constraints have meant that the

institution was unable initiate activities in the water-

shed that would enable the establishment of the

Sixaola Basin Commission. BRIDGE worked with the

Permanent Binational Commission, the governments

of Panama and Costa Rica, partners in the region and

the IUCN Environmental Law Centre to help clarify

the role of the Sixaola Basin Commission, drafting

bylaws and clarifying statutes to enable it to operate

and function as a transboundary basin committee.

Following this, BRIDGE was asked to support prepa-

ration of a Code of Conduct for the Sixaola Basin that

would emphasize the principles of integrated water

resources management and meet the requirements

of the Panamanian and Costa Rican governments.

Working across multiple scales with multiple stake-

holders, water diplomacy in action again delivered a

major step forward in institutionalizing cooperation

at the basin level and preparing the foundation for

a functioning transboundary river basin commission.

BRIDGE’s work in the Andes has focused more

on creating shared data and information plat-

forms, reforming existing institutional structures

and building transboundary governance and water

management capacities in institutions at the national

level. Significantly, achievements by the Zarumilla

Commission have served as a model for cooperation

between Peru and Ecuador, directly influencing water

policy in both countries. Successes in the Zarumilla

basin have strengthened confidence to a point where

both presidents have signed a declaration agreeing

to establish further transboundary basin commis-

sions in the Catamayo-Chira and Puyango-Tumbes

basins, where the BRIDGE project is active. As a

result communities, municipalities and state institu-

tions have begun the process of dialogue and working

together to establish new relationships, improve

communication and formulate agreements across

multiple levels of water users, technical experts and

public officials.

Cooperation catches on in the Goascorán

The goal in the Goascorán watershed is to integrate transboundary

watershed management into broader efforts to improve local livelihoods.

“We start from the assumption that water governance alone is not

sustainable,” says Luis Maier from Fundación Vida. “Good water

management is a function of good land management in a larger sense, one

that includes issues like job creation.”

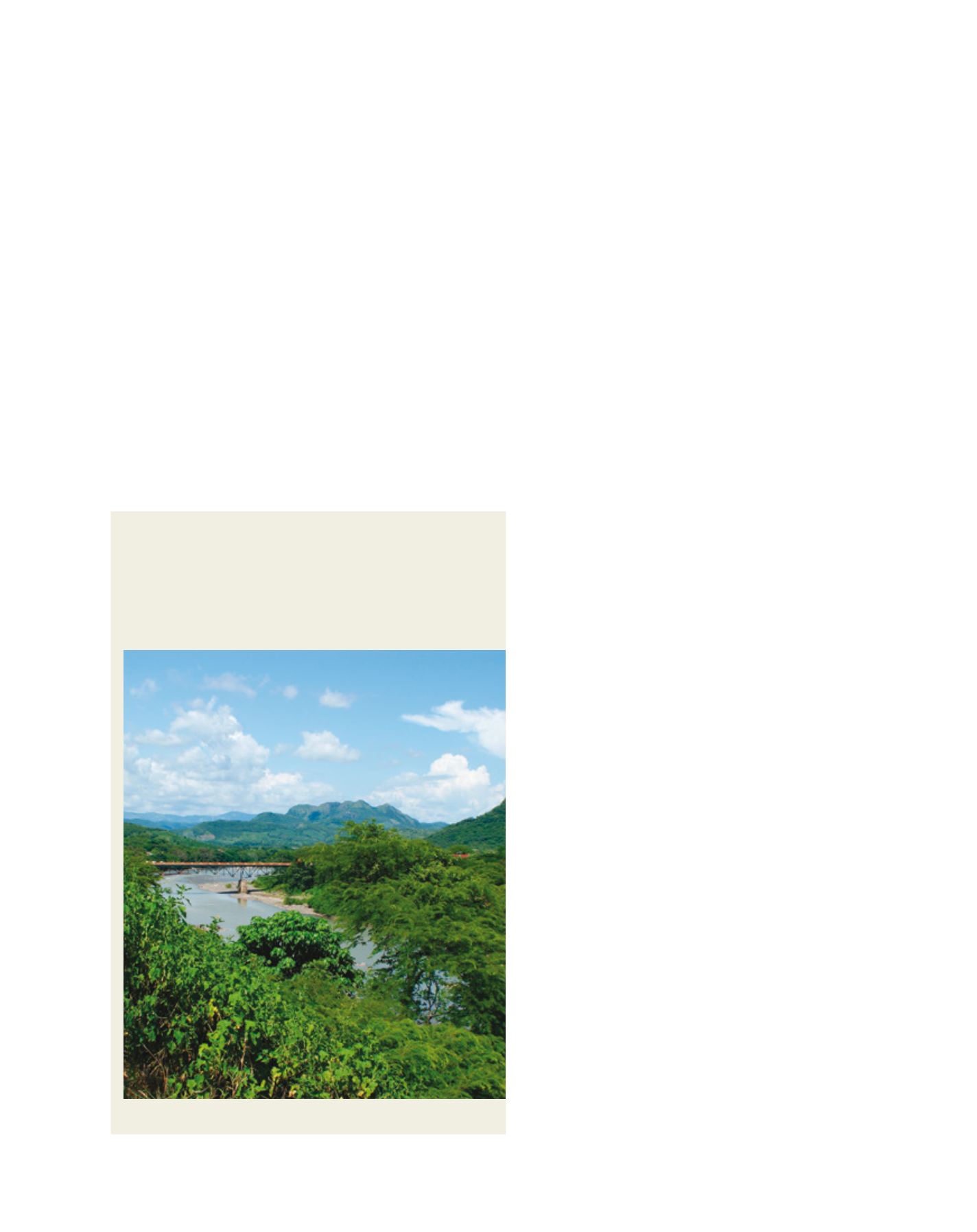

The Goascorán is shared between El Salvador and Honduras

Image: ©IUCN\Manuel Farrias