[

] 32

W

ater

D

iplomacy

can help societies explore and adaptively reform water

governance – rather than assuming that a single model

fits all social and resource contexts.

From the outset, M-POWERmade a deliberate choice to

focus on the wider region, including several international

andmany domestic river basins, rather than to overly focus

on theMekong River Basin and thereby frame toomuch ‘in’

or ‘out’ of different political arenas. The first major public

M-POWER cooperation was in November 2004 when

network members convened, facilitated and provided

catalytic knowledge inputs to a high-level roundtable on

‘Using Water, Caring for Environment: Challenges for the

Mekong region’ at the World Conservation Congress in

Bangkok. The event included ministers from five Mekong

countries (all but Myanmar) as well as non-state actors.

Sensitive issues were tabled for discussion – inter-basin

water diversions into Thailand, Salween hydropower

development in China’s Yunnan province, and threats

to the Tonle Sap ecosystem that would be disastrous for

Cambodia. At the time this was a significant achievement,

specifically bringing China, Lower Mekong governments

and non-state actors into the same arena. The event served

to register the Salween hydropower, Thailand grid and

Tonle Sap threats as transboundary issues of high impor-

tance which deserved to be the subject of multi-country,

multi-stakeholder deliberation.

Oppositional advocacy in (parts of) the Mekong

region is well-developed. Local, national or transna-

tional networks of activists that are organized to resist

dominant institutions, interests and discourses can play

a significant role in decision-making or decision-influ-

encing processes. Under the slogan ‘Our River Feeds

Millions’, the Save the Mekong coalition’s campaign

is catalysed and galvanized by the resurgent interest

in planned dams for the Lower Mekong mainstream.

Campaign supporters argue that these dams pose

extraordinary threats to local livelihoods, biodiver-

sity and natural heritage as the flip-side to energy and

income benefits. The campaign has successfully raised

the profile of dam decision-making by Mekong govern-

ments through the strategic use of photography, media,

letter-writing and direct representation. For example,

more than 23,000 signatures were attached to a peti-

tion warning of the negative consequences of Lower

Mekong mainstream dams, sent to the Prime Ministers

of Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and Viet Nam on 19

October 2009. Due to strategic and persistent advocacy

since 2009, word of the campaign has also reached

distant parliaments in places such as the United States

and Australia.

The Save the Mekong coalition has succeeded in

heightening the understanding of risks to ecosystems

and livelihoods, and is pressing governments – both in

and outside the Mekong region – to take their responsi-

bilities for project-affected people and nature seriously.

A major achievement of the campaign has been to

succeed, despite available science being inconclusive,

in reframing the perceived dams threats from environ-

mental protection to food security and the potential

left out of MRCS activities or perceive the MRCS to encroach on

their national space. In turn, the NMCSs must also establish their

own role and working space within their national polities, with their

functional power much less than key water-related ministries and

agencies in each country. As in any large family, it is not possible

for all the interaction to be smooth. The vaunted ‘Mekong spirit’ of

cooperation often seems optimistically overstated; but that is not

to deny the importance of doing everything possible to encourage

a constructive spirit between the countries sharing precious water

resources, risks and opportunities.

The M-POWER network has been working since 2004 implement-

ing a Mekong Program for Water Environment and Resilience. The

vision for the network is for the region to realize an internation-

ally accepted standard of democracy in water governance. A core

objective is to make it normal practice for important national and

transnational water-related options and decisions to be examined

in the public sphere; another is to support the development of

governance analysts with experience across the region. M-POWER

takes a broad view of democratization, interpreted as encompass-

ing issues of public participation and deliberation; separation of

powers; accountability of public institutions; social and gender

justice; protection of rights; representation; decentralization; and

dissemination of information. Network members believe that action-

research, facilitated dialogues and stronger knowledge networks

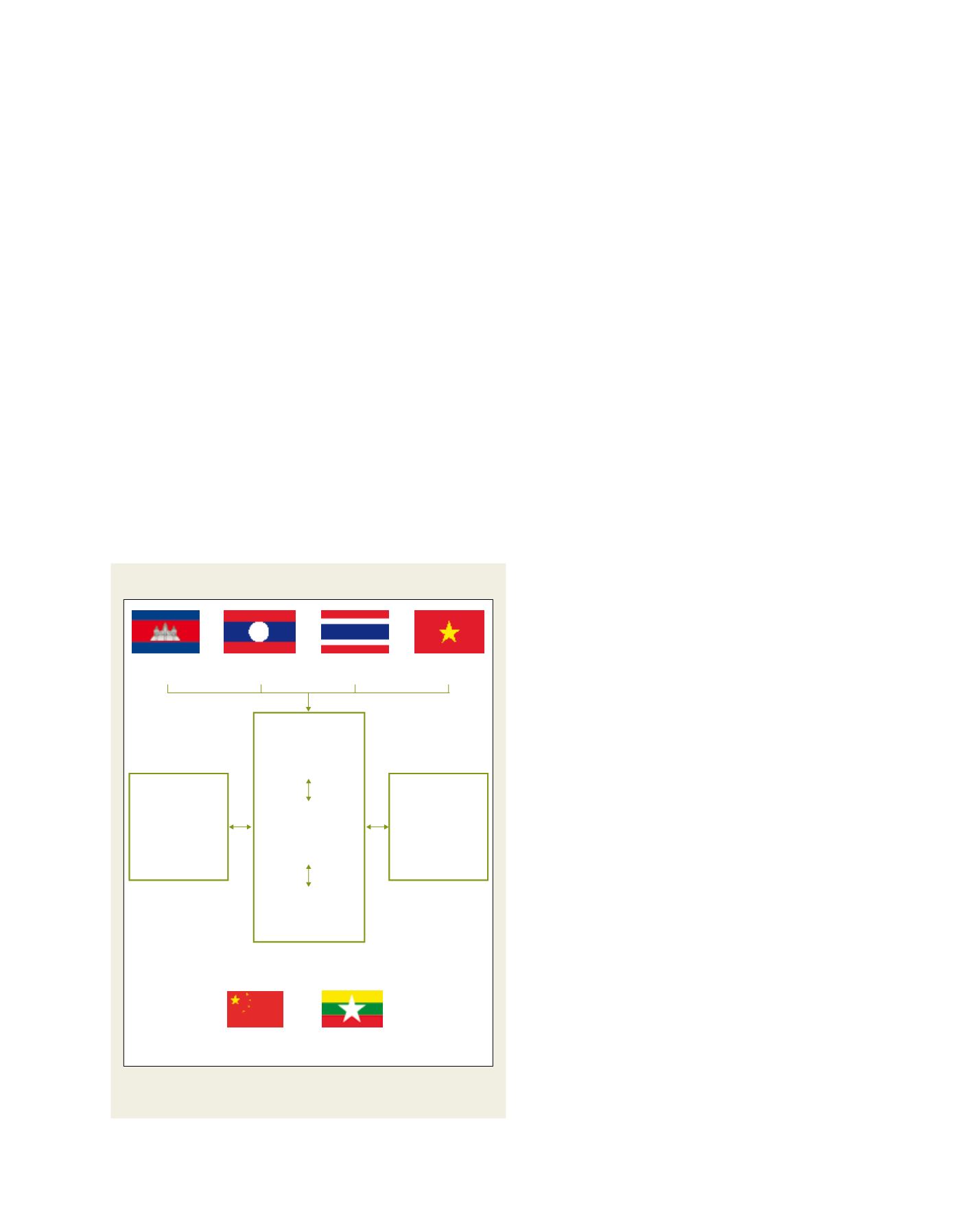

Organization of the Mekong River Commission

Government of

Cambodia

Government of

Lao PDR

Government of

Thailand

Government of

Viet Nam

Donor Consultative

Group

Development

partners and other

cooperating

organizations

National Mekong

Committees (NMCs)

NMC Secretariats

Line agencies

Dialogue Partners

MRC Secretariat

Technical and

administrative arm

Joint Committee

Members at Head

of Department level

or higher

Council

Members at

Ministerial and

Cabinet level

Government of

China

Government of

Myanmar

The organizational structure of the Mekong River Commission entails many

elements in a complex political dynamic

Source: Mekong River Commission