[

] 34

W

ater

D

iplomacy

• multi-stakeholder platforms exploring alternative

futures are used to build the trust and cooperation

needed for actors to work together to help resolve

water allocation issues

• e-flow assessments are used to clarify risks and

benefits of different flow regimes on different water

users and ecosystems

• scenario building, with the participation of

marginalized people’s representatives, is used to

improve transparency by clarifying and probing

actors’ assumptions and motivations

• strategic environmental assessment is used to

explore the broad impacts of existing, proposed and

alternative development policies and plans early on

• holistic modelling is used to quantitatively assess

impacts of scenarios and development policies and

to generate base information for impact assessments

• oppositional advocacy pressure is maintained to

ensure that political space is available for civil

society and concerned actors to safely contest and

contribute to policies, proposals.

Transboundary water diplomacy is not only the province

of state actors. Across the Mekong region, there is much

diplomacy underway with multiple actors manoeuvring to

try and shape development directions and decisions. This

is increasing the likelihood that decisions will be the result

of informed and negotiated processes that have assessed

options and impacts, respected rights, accounted for risks,

acknowledged responsibilities and sought to fairly distrib-

ute rewards–the essence of deliberative water governance.

Image: K G Hortle

to all but privileged insiders. Meaningful public deliberation is still

the exception rather than the rule. Nevertheless, more recently, we

have seen a deliberative turn and hopeful signs of water governance

change, for example:

• vibrant elements in the Chinese media interested in

understanding and reporting the water-related perspectives of

neighbouring countries

• a pause and reconsideration of future development in a

new era for Myanmar

• an increasingly inquisitive National Assembly in Laos

• bold inputs to public policy-making debates by

Vietnamese scientists

• increased space for civil society analysts in Cambodia to engage

in state irrigation policy debates

• people’s environmental impact assessment in Thailand, building

on villager-led Tai Baan participatory action research and

resulting in more participatory analyses of project merits.

Finally, Lower Mekong mainstream dams are now being exam-

ined more openly. This is a result of many factors, including an

MRC-commissioned strategic environmental assessment and a

subsequent formal prior-consultation process facilitated by MRC,

which has yielded various technical contributions and opened an

intergovernmental window for more informed discussions between

Lower Mekong countries. Each of these processes has been improved

by advocacy from civil society, science, academia and governments

–including MRC, M-POWER and Save the Mekong.

In the Mekong we have found that water diplomacy is improved

by bringing different perspectives into arenas and fostering delibera-

tion to inform and shape negotiations and decisions. Specifically, we

suggest that transboundary diplomacy will be further improved when:

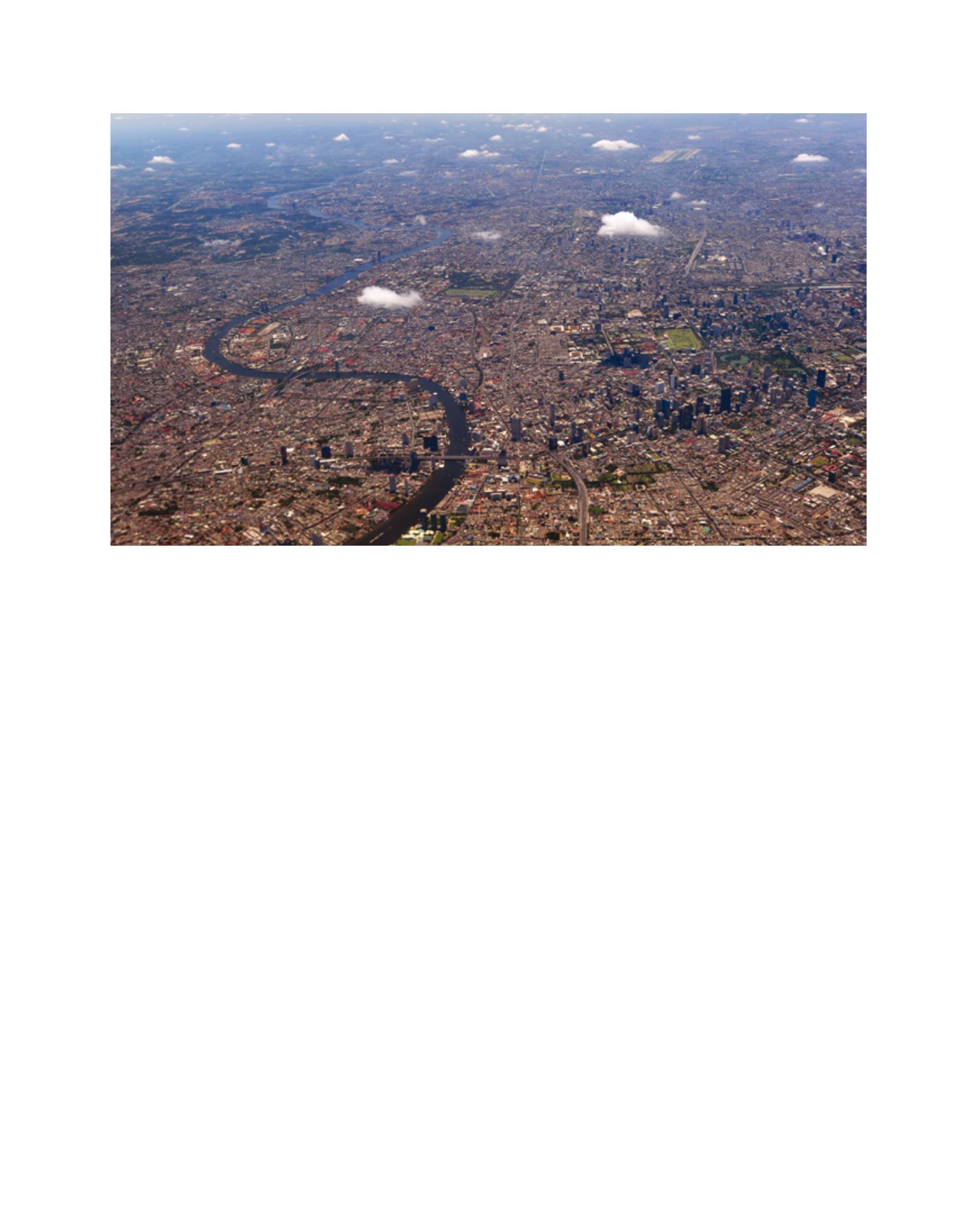

Bangkok, Thailand, the mega-city destination for much of the proposed hydropower energy production in the Lower Mekong