[

] 33

W

ater

D

iplomacy

for economic disaster. This has contributed to greatly elevating the

issues in the minds of regional and international policymakers.

Transboundary diplomacy is required and deliberation – debate

and discussion aimed at producing reasonable, well-informed opin-

ions – has been in short supply, despite decades of ‘cooperation’.

Deliberation is an important process because it requires supporters

of policies and projects to articulate their reasoning and identify

which interests they serve or risks they create.

Decision support tools that support deliberation are increasingly

being used to inform Mekong water-related diplomacy. These tools,

used effectively, assist the exploration of options, examination of

technical outputs and contestation of discourses. Tools that should

be explicitly rooted in deliberation include multi-stakeholder plat-

forms (MSPs), environmental flows (e-flows) and scenario-building.

MSPs can help routinize deliberation, enabling complex water issues

to be more rigorously examined in better informed negotiations. This

is not to say that MSPs are a panacea. For example, we have observed

that MSPs can be captured by players who are able to frame and control

the debate and keep it confined within the limits of their choice. We

have also seen MSPs permitted to engage many stakeholders in good

faith, only to be ignored in subsequent decision-making. Despite these

caveats, we have found that networks and organizations with flexible

and diverse links with governments, firms and civil society have been

useful to convene and facilitate dialogues on sensitive but important

topics for development in the Mekong region. The outcomes of these

are not primarily in terms of direct decisions on projects, policies or

institutional reform; but rather in making sure alternatives are consid-

ered and assessed, a diversity of views and arguments recognized, and

mutual understanding improved.

E-flow-setting requires the integration of a range of disciplines

from across the social, political and natural sciences. Above all, it

requires processes of cooperative negotiation between

various stakeholders that help bridge their different and

often competing interests over water. Hence, e-flows are

well-suited to MSP approaches. There have been few

applications of e-flows in the Mekong region, but some

with which the authors are very familiar include rapid

e-flows assessments of the Huong River in Viet Nam

and Songkhram River in Thailand, and an integrated

basin flow management project of the Lower Mekong

River. E-flow processes have substantial potential in the

Mekong region to assist river basin managers as they

grapple with competing demands, including the need for

environmental sustainability. At present, however, the

tool has only been used in academic or technical settings

and has not yet been internalized into influential deci-

sion-making arenas.

Deploying scenarios can enhance MSPs, e-flows and

other deliberative forums. Scenarios should improve

understanding of uncertainties, not hide them. The goal of

formal scenario analysis is to generate contrasting stories

of what the future of a geographical area, policy sector

or organization might look like, depending on plausible

combinations of known, but uncertain, social and envi-

ronmental forces. The analyst and others participating in

the process should gain insight into the contrast between

alternative stories. Good scenarios are rigorous, self-reflex-

ive narratives: they attempt to be internally coherent, to

incorporate uncertainties and to be explicit about assump-

tions and causality.

We observe that core decision-making processes

about water in the Mekong region are still often opaque

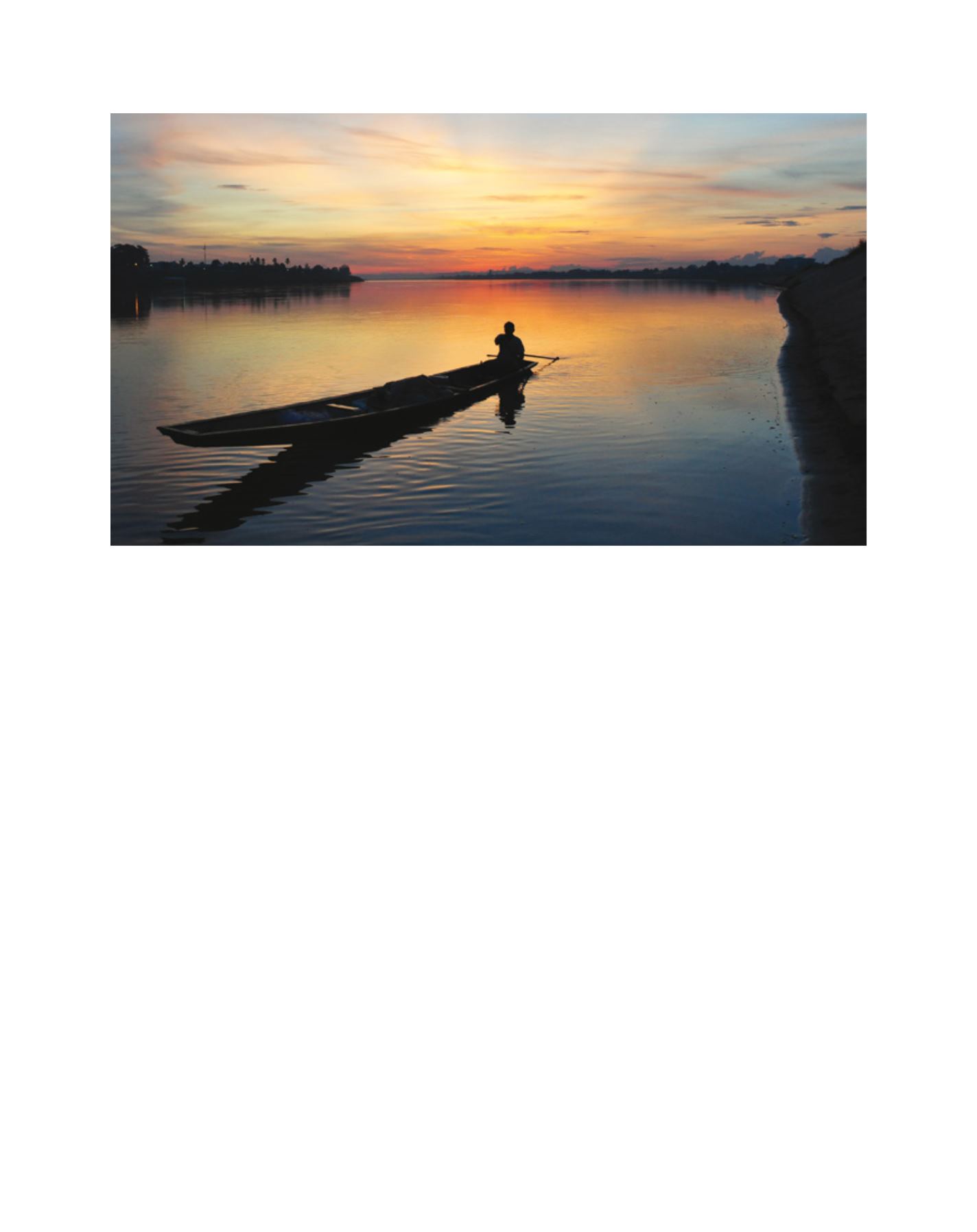

A Mekong river fisherman at sunset in Vientiane, Lao People’s Democratic Republic

Image: K G Hortle