[

] 36

W

ater

D

iplomacy

for clean hydropower development and power trade; for

expanding agricultural production and increasing water

use efficiency; for the preservation and ecotourism use

of biospheres and designated hotspots of unique biologi-

cal diversity; for utilizing the Nile as an entry point for

broader economic-regional integration, promotion of

regional peace and security; and not least for jointly

ensuring the continued existence of the Nile through

prudent and judicious utilization.

The Nile Basin Initiative

Growing recognition of the above challenges, and the real-

ization of the potential inter-riparian conflict that would

ensue from poorly managed, increasingly shrinking and

scarce Nile water resources, spurred the member coun-

tries to formulate a shared vision1 and establish NBI in

February 1999, with significant support from the inter-

national community. NBI is headquartered in Entebbe,

Uganda with two subsidiary action programme offices in

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Kigali, Rwanda. NBI has three

core functions, namely facilitating cooperation, water

resources development and water resources management.

NBI fills an important gap that has been a barrier to the

joint and sustainable management of the common Nile

Basin resources. It is a transitional mechanism that will

phase out when the Nile River Commission is established.

NBI has had several key achievements in its three core

functions, along with various challenges and lessons in

transboundary cooperation.

Facilitating cooperation

NBI has provided the first and only inclusive platform

for dialogue among all riparian states. Given the earlier

history of non-cooperation characteristic of the Nile

Basin, creating an enabling environment was made a

priority. This included building transboundary insti-

tutions and raising awareness; building inter-riparian

for example, 157-207 million tons of topsoil is washed away annu-

ally, resulting in economic loss upstream and downstream. In the

midstream, important wetlands – critical in regulating the hydro-

logical balance and river flow, hosting endangered flora and fauna,

and providing environmental services to local communities – are

shrinking. In the most downstream reaches in the delta, salt water

intrusion into the Nile is posing growing challenges.

Across the entire Nile Basin, biodiversity hotspots and unique habi-

tats are increasingly disappearing.Both due to sheer demographic

pressure and demand driven by economic growth, the stress on

the finite and fragile water resources of the Nile is likely to grow to

unmanageable proportions. The problem is compounded by the fact

that each riparian country plans and implements its national water

resources development plan on the Nile in unilateral fashion. Limited

understanding of the science of the river; institutional insufficiency at

national and transboundary levels; and inadequate understanding of

the impact of climate change on the Nile – all these add complexity

to the management of the common resources of the Nile.

The Nile Basin has been characterized by a preponderance of intra

and inter-country conflicts and political instabilities. Conflicts and

civil strife related to electoral politics have been common features.

The intensity and costliness of the conflicts has been aggravated by

direct or proxy support of combatants across borders.

Alongside these challenges, the Nile Basin offers significant poten-

tial for a win-win outcome from cooperative management and

development. Among others, the basin harbours noteworthy potential

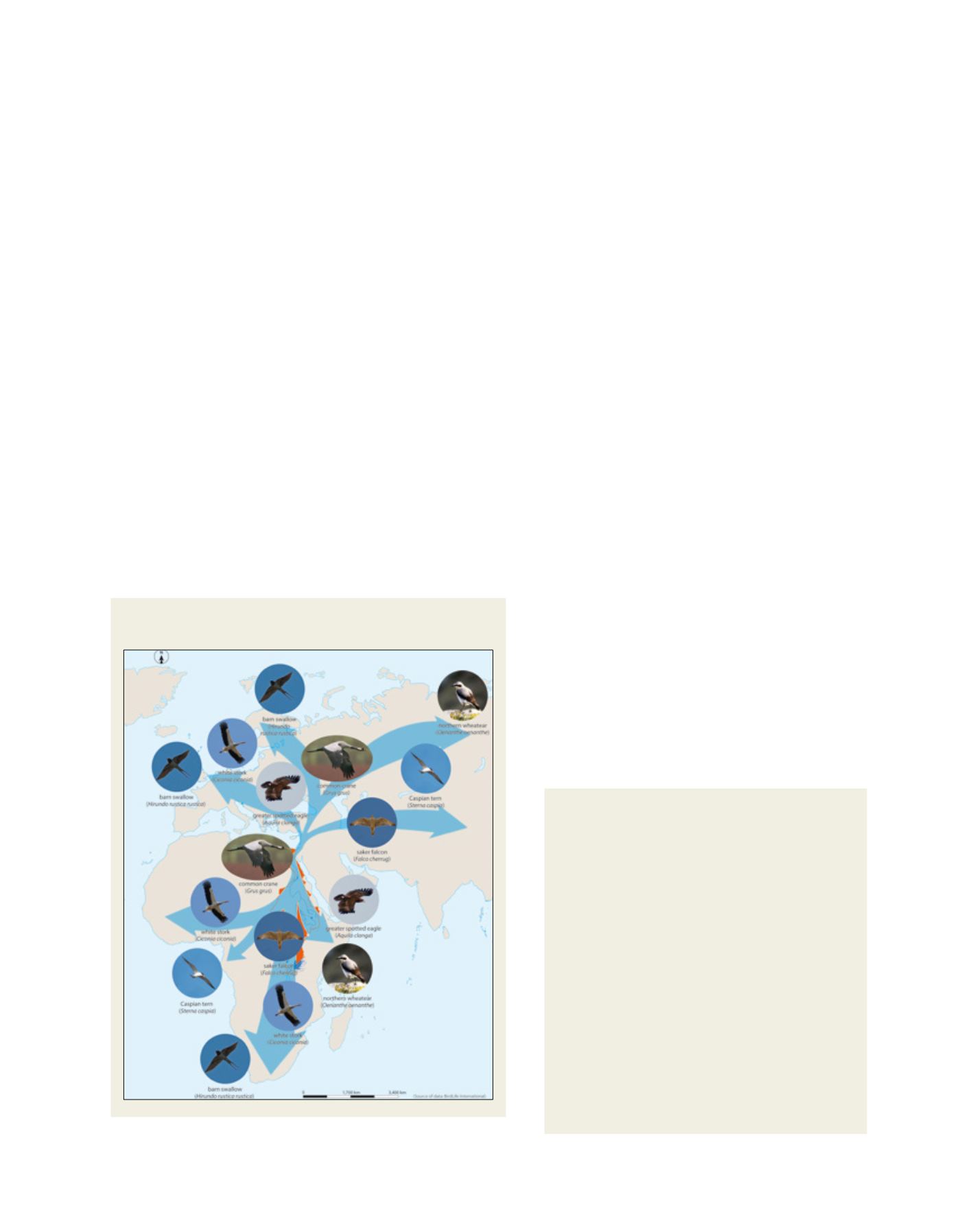

Flyways of selected birds dependent on the Nile Basin for a

stop-over or over-wintering

Source: NBI State of the Basin report, 2012

Community watershed management

project – Sudan

The Dinder and Lower Atbara watersheds are the focus

areas of this fast-track watershed management project.

The former, in the Blue Nile, is also home to the Dinder

National Park – a designated biosphere. Pastoralists

often encroach into the park on their way to find grazing

land and watering points, which creates conflicts.

This project has scored remarkable achievements in

a short period. Over 27,000 ha of degraded agricultural

land has been rehabilitated; farm yield for dominant

crops has shown significant improvement, with sorghum

yield increasing from a baseline 519 kg/ha to 1,249

kg/ha in Dinder and from 1,249 kg/ha to 3,391kg/ha

in Atbara. Similarly, sesame yield has increased from

202 kg/ha to 336 kg/ha in Dinder and white bean

yield has increased from 887 kg/ha to 2,480 kg/ha in

Lower Atbara. Over 300 km of livestock routes have

been mapped, demarcated and opened for pastoralists,

which will relieve en route conflicts. Over 5,010 ha of

rangeland has been reseeded with nutritious and soil

rehabilitating varieties of fodder. Fodder production has

been initiated in 24 villages.