[

] 48

T

ransboundary

W

ater

M

anagement

following categories: economic well-being; social and human develop-

ment; education and training; and sustainable ecosystem and natural

resources management.

These two initiatives demonstrate two different approaches to

mobilizing local populations for transboundary water management.

On one side, the GWN has favoured the twinning of communities,

while on the other side the ERP has facilitated the emergence of a

basin-wide network. These approaches have been designed firstly to

match the characteristics and profiles of the territories where they

have been implemented. In the political context of the Jordan basin,

it is a challenge to organise regional meetings on a regular basis. The

logistical and political constraints between Jordan, Israel and the

Palestinian territories are the major obstacle to implementing such

a mechanism in this basin.

NGOs played a key role in the achievement of these successful

enterprises. They initiated the projects, supported and followed the

communities by teaching them and showing them how to improve

their environment, and facilitated the relations among and between

the parties: communities, political authorities and international

donors who funded these projects.

In both cases, the success of these initiatives has been built

around three steps: identification of the population needs, capac-

ity building and financial independence. Apart from the dedicated

trainings and workshops, the participation of the communities

in these projects was a capacity building programme by itself.

Through the different activities implemented, the communities

could develop their technical, administrative and negotiation

knowledge and abilities. This allows them to play a more effective

role in transboundary water interactions.

In both cases again, the NGOs looked for executing income-gener-

ating activities to decrease communities’ dependence on external

funding. Neighbours‘ Paths, trophy hunting or handicrafts have been

developed to provide a supplementary source of income

to communities and to alleviate poverty in poor areas.

These community transboundary projects have

enabled communities to:

• Build a peaceful environment to manage

transboundary water resources

• Improve water management at the local level with a

direct benefit for its inhabitants

• Reduce poverty with participative practices and the

creation of new income generating activities

• Strengthen relational and social learning among

communities from the different sides of the border

• Develop communities’ knowledge and reflection on

their practices, their respective issues, their causes

and their consequences.

Transboundary cooperation is not only a venue for

high-level political players; local communities have a

role to play as well. The participation processes applied

in the Jordan and Okavango basins facilitated water

cooperation, sustainability and poverty reduction. A

community identity has arisen, not associated to a

country, but to a river basin. An international NGO,

the International Secretariat for Water, is promoting

this ideal and has created a Blue Passport to reinforce

citizenship awareness throughout river basins world-

wide. All basiners can obtain their Blue Passport to

affirm that they belong to a hydrographical ecosys-

tem and to demonstrate their commitments for water

in their river basin. In addition to being citizens of

Namibia, Botswana or Angola, people can now claim

their citizenship of the Okavango River Basin.

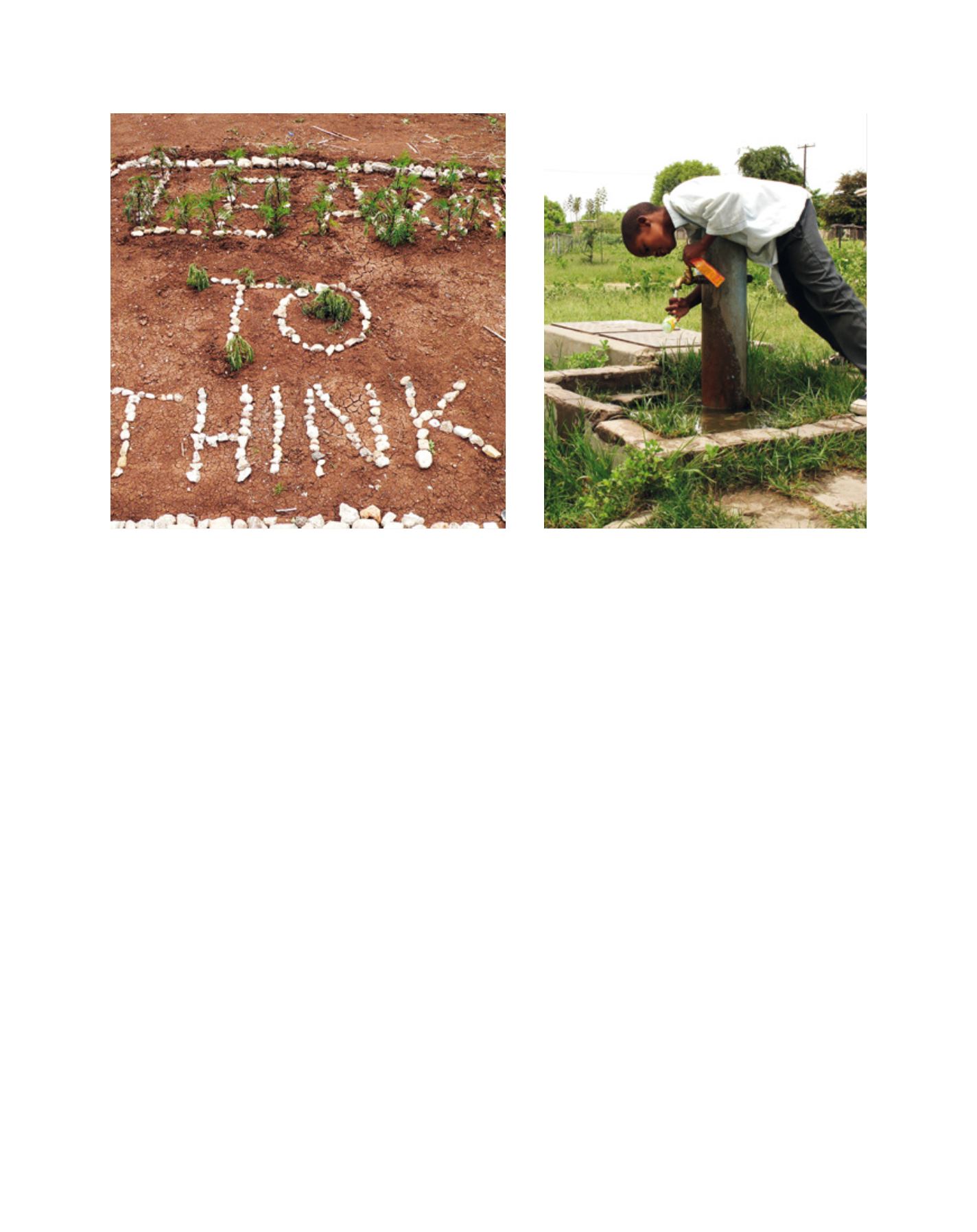

Ecological gardens have been built in local schools in the Jordan River Basin

Water pump in Seronga, Botswana

Image: B Noury

Image: B Noury