[

] 52

T

ransboundary

W

ater

M

anagement

may be the case, it is clear that such an assertion should

not be overextended.

19

Phillips and others point out

that the level of securitisation in a river basin is an

impediment to a functionalist (cooperation leading to

cooperation) approach since the preoccupation of the

states will be on national security, thereby clearly limit-

ing the room for regional perspectives.

20

This is clearly

evident in places like the Jordan Basin,

21

but also in

other regions with a strong security focus. This does not

mean that cooperation cannot happen, but the asser-

tion that this would almost automatically lead to wider

cooperation is far-fetched.

The challenges faced by the international commu-

nity are daunting. However, development partners

can contribute to overcoming these challenges by

supporting the processes of cooperation that underpin

systems of best or ideal practice in transboundary water

management. Staying for the long haul is essential to

the achievement of sustainable and effective cooperative

outcomes. Öjendal and others

22

conclude that, given

the challenges at hand – compounded by the uncer-

tainties surrounding climate change and increased

population growth – it is more relevant than ever to

discuss transboundary water relations as a matter of

continuous negotiation.

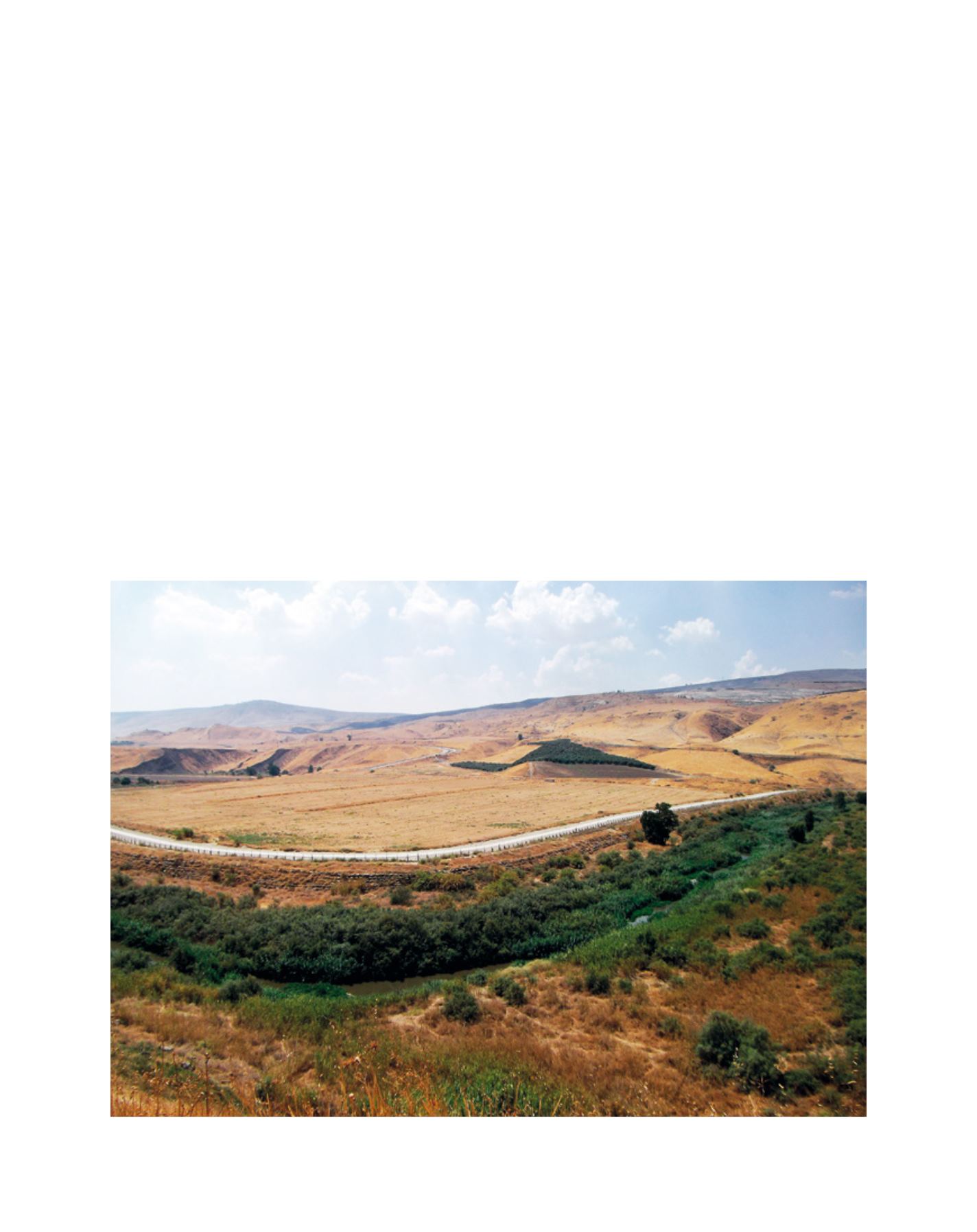

The Jordan River along the Jordan-Israel northern border: there are some encouraging signs of cooperation over shared waters in the Middle East

Image: Rami Abdelrahman, SIWI 2013

still exist deep cleavages between neighbouring nations. However,

there are some encouraging signs of cooperation over shared

waters. There are, in fact, situations where water seems to be

the singular bond between countries that have been historically

prone to conflict. For example, the Jordan Basin features a peace

agreement between Israel and Jordan that regulates water alloca-

tions stemming from the Jordan River to quite a large extent and

even includes a provision for storing of Jordanian ‘winter water’

in Lake Tiberias in Israel for later release during the dry summer

months when the water is needed. Since the signing of the agree-

ment in 1994, there has been a functional relationship – albeit

not always smooth – made possible by the parties’ arrangement to

share water. Alternatively, the distinct power asymmetry between

Israel and Palestine has prevented a similar arrangement between

those two countries. Since Palestine does not have the same politi-

cal clout regionally or internationally as Jordan, it is all too easy

for Israel to dominate the water situation. Consequently, there is

no fully-fledged agreement between them addressing water issues,

either quantitatively or qualitatively, in great detail. Although it

is noted in current agreements that the Palestinians have ‘water

rights’– those rights are not clearly defined.

18

Conclusions

It has been suggested that regional cooperation over water as a

shared resource can be a recipe for wider cooperation. While this