[

] 43

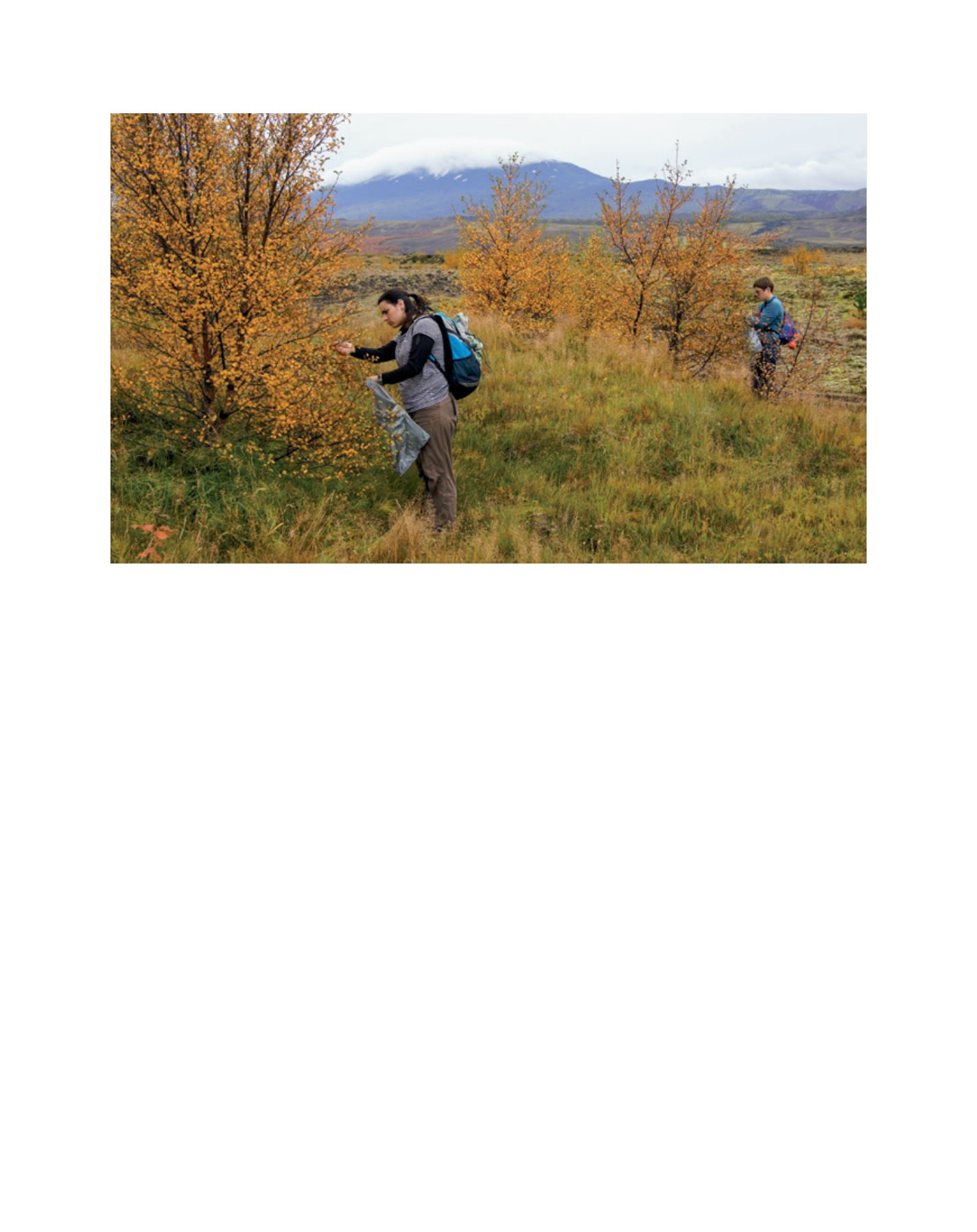

tation following each eruption. Currently most of the area is

eroded, the soil is poor in nutrients and water-holding capacity,

and frost heaving is extensive. Erosion is extensive; primarily

wind erosion but also water erosion the during the spring thaw.

Therefore, natural establishment of seedlings is limited.

Local farmers or landowners, SCSI, IFS, regional afforestation

projects and local forestry associations have been working on

stopping the erosion and restoring the vegetation in the area

since the nineteenth century. The early efforts were mainly

focused on protecting local farmhouses and hayfields from

the sand and creating grazing areas. Later the work dealt with

protecting larger areas from sheep grazing; spreading fertilizer,

especially nitrogen and phosphorus; and seeding grasses and

nitrogen-fixating species, mainly Nootka lupine. Trees have

been planted or sown in reclaimed areas with good success, and

natural colonization of birch can be found around both the old

remnants of the birch forests and younger plantations, which

suggests that tree planting is a feasible method in the area.

The eminent results from these restoration activities were

the main arguments for the establishment of the Hekla forest

project. Its primary goals are to increase the resilience of the

ecosystem to deposits of volcanic ash during eruptions in the

volcano and to prevent secondary distribution of the ash by

wind and water. Other goals are the restoration of ecosystem

function and biodiversity, carbon sequestration and improved

options for future land use.

From the very beginning, the project was based on building

effective partnerships and the involvement of various stake-

holder groups in the process. Local farmers, governmental

organizations and NGOs formed a collaboration committee

for the project. They contributed actively to planning and

promotion until the project was officially approved by the

state as an independent governmental project, run by the

state with funding from the business sector. Since then, the

committee’s role has changed to be mainly advisory.

Local landowners and other volunteers participate actively

in the project, mostly by planting birch seedlings provided by

the project. The project area extends over 90,000 hectares.

Due to the size of the area, low-cost methods are essential.

Therefore, the restoration of woodlands will mostly rely on

colonization of birch and willows rather than large-scale plant-

ing. Birch seedlings are planted in small groves or woodland

islets, from which these species will colonize surrounding

areas during the next decades. However, stabilizing the soil

in the nearby areas is needed to create favourable conditions

for woodland expansion by seed. This is done by spreading

inorganic or organic fertilizer onto the land in order to facili-

tate the establishment of soil crust and local flora. Sowing a

mixture of grass species is also needed in some areas.

Since the Hekla forest project started in 2007, all planting,

spreading of fertilizers and sowing of grass has been mapped

and stored in a GIS database. Several research projects have

been conducted in the area and some are ongoing, looking at

both ecological factors and cultivation techniques.

In 2015, 215 landowners had joined the project and more

than 2.5 million seedlings had been planted. The afforested area

covered more than 1,300 hectares, divided into numerous small

patches throughout the area which have already started to facili-

tate self-seeding. The project has been successful and will be a

model for other similar projects in Iceland in the years to come.

Image: Hreinn Óskarsson

Birch seeds are collected in September and sowed in the autumn

L

iving

L

and