[

] 94

75 per cent of Israeli irrigation relies on drip systems, roughly

half of which involve subsurface systems. Paradoxically, as

the systems’ sophistication increased, prices began to drop.

While Israeli agriculture was embracing drip irrigation, a

parallel process took place in terms of irrigation water: treated

sewage effluents became the predominant source of water for

Israel’s agriculture sector. Standards were set for reuse of

effluents and in 1956 a national masterplan was adopted that

envisioned the ultimate utilization of 150 million cubic metres

by Israel’s agricultural sector. Today, three times that amount

of treated wastewater is recycled. As of 2015, the country

recycles 86 per cent (400 million m

3

) received at its treatment

plants. This is a far greater commitment than other countries.

For instance, Spain, the European leader in the field, report-

edly recycles 12-17 per cent of its sewage; Italy and Australia

roughly 10 per cent. Over half the irrigation water used by

farmers in Israel today is recycled effluents (50 per cent at

secondary treatment levels and 50 per cent tertiary), allowing

for the cultivation of 130,000 hectares of agricultural lands.

Reuse of treated sewage can substantially expand water

resources but is not without environmental and public health

ramifications. Recycling sewage initially raised concerns

about microorganisms: beyond affecting farmers deleteriously

through direct contact, irrigated effluent can leave consumers

exposed to produce with a range of harmful bacteria. Over the

years, upgraded Israeli wastewater treatment levels largely elim-

inated this hazard. Improved compliance with the Ministry of

Health’s effluent irrigation standards, which stipulated increas-

ingly high water quality standards for irrigating different crop

types, also contributed to substantially reduced risk.

Not all contaminants are easily removed through treatment.

For instance, boron is a critical element for plants but is toxic

when concentrations are excessive. As conventional sewage

treatment does not eliminate boron, its presence in effluents

began to affect crop yields in the 1980s. Israel quickly moved

to ban boron in laundry detergents and immediately improve

the recycled wastewater quality provided to farmers.

Other ‘microcontaminants’ such as pharmaceutical resi-

dues, remain a problem. Hebrew University’s Benny Chefetz’s

laboratory has identified high concentrations of pharmaceu-

tical compounds such as lamotrigine (an anticonvulsant

drug) in crops irrigated with secondary treated wastewater

that cross the threshold of toxicological concern (TTC) level

for a child (25 kg) who consumes half a carrot a day (60 g

carrot/day). Consumption of sweet potato leaves and carrot

leaves by a child (25 kg) would also surpass the TTC level for

epoxy-carbamazepine (an epilepsy drug) at 90 g leaves/day

and 25 g leaves/day, respectively. The risks associated with

these ‘contaminants of emerging concern’ are only now being

characterized, but they are probably of less concern than the

oldest water pollutant of them all: salinity.

Salts, almost without exception are not removed during

sewage treatment fromwastewater streams. Wastewater by defi-

nition has higher salinity relative to its contributing background

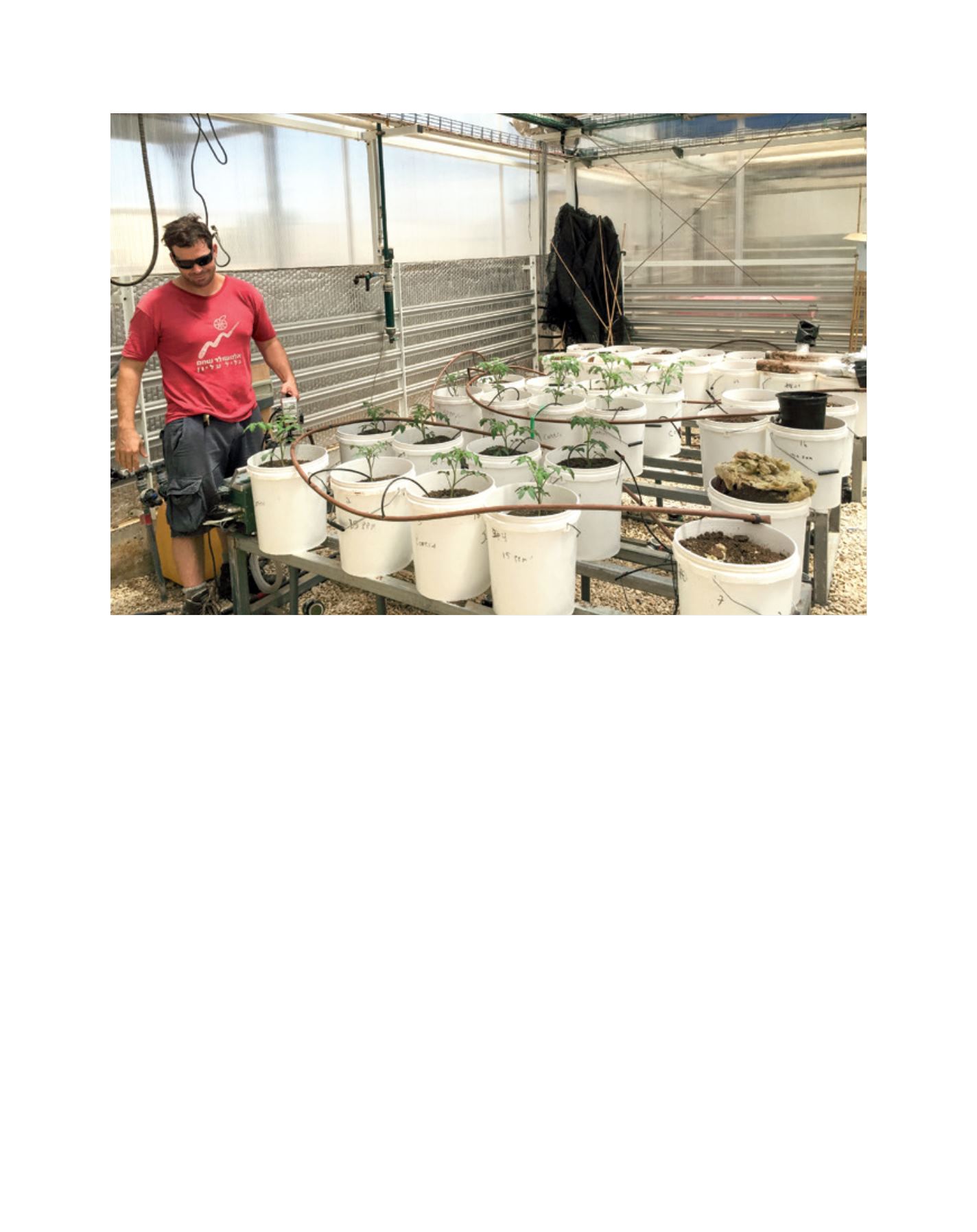

Ben Gurion University researchers evaluate the efficacy of irrigation waters with different salinity levels

Image: Alon Tal

L

iving

L

and