[

] 179

Democratizing education:

the quantity and quality debate

Maya Dodd, Foundation for Liberal and Management Education, Pune, India

S

ince the 2005 launch of the UN Decade of Education

for Sustainable Development, India has realised several

initiatives, by both the government and the private sector,

towards achieving greater equality in the education sector.

There is, at last, a real recognition of the fact that there cannot

be sustainable growth without basic investment in the country’s

human resources through a systematic education system that

caters to capacity-building. Much effort has gone into the creation

of an infrastructure that can achieve this end. However, despite

recent wide, sweeping reforms in Indian education at the school

level, reviews of India’s college education structure are clouded by

endless controversies. The demands to ‘liberalize’ college educa-

tion have leaned on the need for new investment by the private

sector at a critical juncture of India’s growth. However, for one-

fifth of the country’s population, the biggest challenge faced is

the absence of quality in current standards of college education.

The inadequacies in educating vast numbers of Indian young

people far exceed issues of regulation or demand-supply deficits.

Debates plaguing the Knowledge Commission’s recommenda-

tions to dissolve the University Grant’s Commission’s control of

universities; the scandal of abuse of powers by the Indian Medical

Council in legitimizing colleges; the indiscriminate

rise of private education in engineering and manage-

ment under the purview of the All India Council on

Technical Education; and the overall neglect of more

inclusive regulations for vocational education all point

to the general observation that undergraduate educa-

tion in India is in desperate need of an overhaul.

The real crisis lies beyond challenges of scale

and the rationale of which agents are responsible

for providing India’s young people with colleges. If

all debates on education have been reduced to the

urgency of accommodation, post-secondary education

has been especially afflicted by a history of deflecting

debates on the quality of education by invoking the

spectre of numbers. Since independence in 1947, the

number of colleges in India increased over 60 years

from under 500 to the current total of over 20,000.

This educational infrastructure can accommodate only

seven per cent of all of India’s college-age students,

and the low enrolment ratios of today mirror this fact.

While by 2010, the population of the 15–24 age group

was estimated at 19 per cent of the total population,

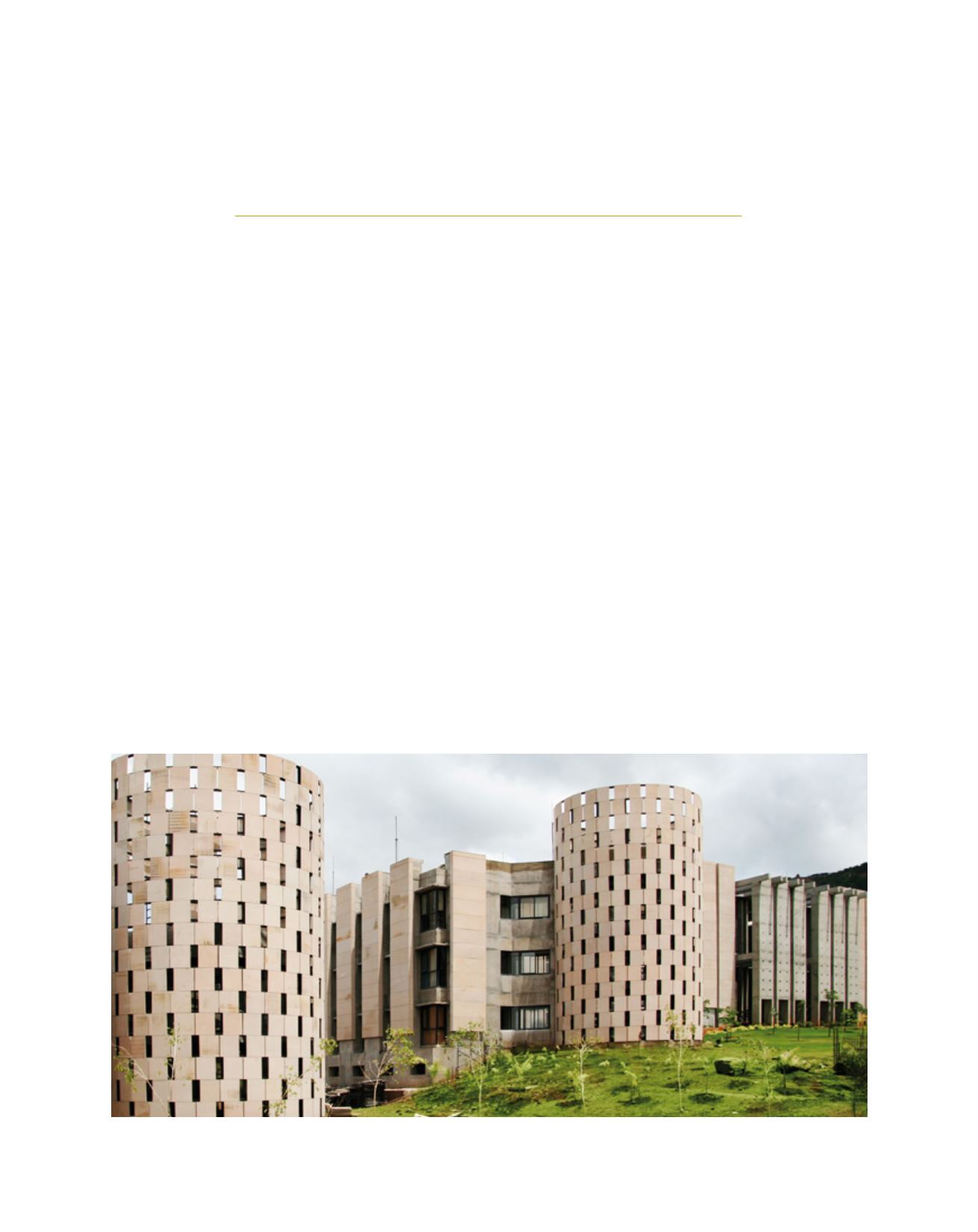

The FLAME campus in Pune, India

Image: FLAME