[

] 11

75 million and 250 million people in Africa may be

exposed to increased water stress due to climate change;

in some countries yields from rain-fed agriculture could

be reduced by up to 50 per cent. By 2050, freshwater

availability in Central, South, East and South-East Asia

is projected to decrease, particularly in large river basins.

Europe’s mountain glaciers will retreat, reducing snow

cover and winter tourism, and high temperatures and

droughts will worsen in southern Europe. Yields of some

important crops and of livestock in Latin America are

projected to decline. Warming in the western moun-

tains of North America is projected to cause decreased

snowpack, resulting in more winter flooding and reduced

summer flows.

The science of climate forecasting

To generate actionable information for addressing these

and other climate risks and opportunities, the providers

of climate services must, of course, be able to forecast

the climate. But if forecasters cannot predict next week’s

weather, how can they predict the longer term climate?

A fair question. Of course, meteorologists

can

predict

next week’s weather, even if the inherent chaos of the

atmosphere means they sometimes get it wrong. The

weather forecaster’s challenge is that small random

movements of air and moisture can divert a broader

weather pattern, especially at the local level and beyond

the timeframe of a week or 10 days.

These small-scale chaotic movements do not affect

climate, often defined as the average weather over a

30-year time period. Climate forecasters do not need

to predict whether it will rain in Beijing on Tuesday;

rather, they aim to predict that the next winter (or

drought draws down reservoirs and other supplies. The failure of the

monsoon can lead to hardship and hunger. As the climate changes, the

distribution of water resources may permanently shift; for example,

melt water from glaciers may be released earlier in the spring, affecting

fishing, irrigation, energy production and water supplies.

Climate is also the force behind most disasters caused by natural

hazards. Many parts of the world are vulnerable to floods, droughts

and severe storms. Seasonal climate variation and extreme rain can

contribute to landslides and erosion. As greater warmth speeds up

the water cycle, and the warmer atmosphere holds more water, more

flooding and severe storms can be expected.

By exacerbating climate variability, climate change will increase

the need for climate services. The 2007 assessment report of the

WMO/UNEP Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)

estimates that the average global temperature (which is now 15° C)

will likely increase by 1.8-4.0° C by the end of the century. This

would result in an estimated sea-level rise of 28-58 cm – although

larger values of up to 1 m by 2100 cannot be ruled out. The IPCC

will update these projections in late 2013 based on the most up-to-

date research available.

A number of changes in the climate have already been observed.

The world’s rivers, lakes, wildlife, glaciers, permafrost, coastal zones,

disease carriers and many other elements of the natural and physical

environment have started responding to the effects of humanity’s

greenhouse gas emissions. Rising temperatures are accelerating the

hydrological cycle, resulting in heavier rains and more evaporation;

they are also causing rivers and lakes to freeze later in the autumn

and birds to migrate and nest earlier in the spring. Scientists are

increasingly confident that, as global warming continues, certain

weather events and extremes will become more frequent, wide-

spread or intense.

Scientists are also starting to predict how the climate will change

in specific regions. According to the 2007 report, by 2020 between

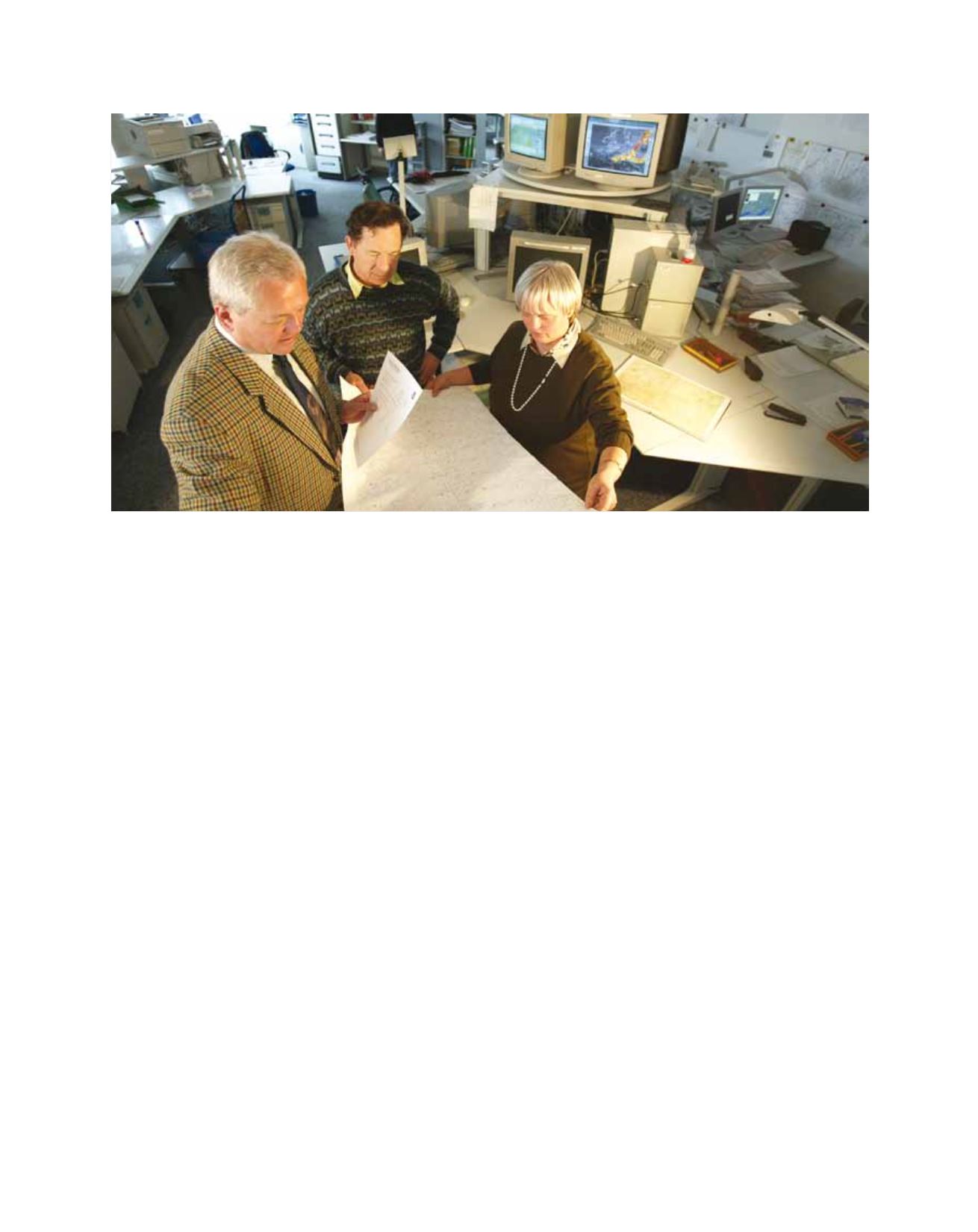

Forecasters at Deutscher Wetterdienst study weather maps

Image: Deutscher Wetterdienst

C

limate

E

xchange