[

] 252

A

daptation

and

M

itigation

S

trategies

not want this debt to become entangled with the broken

promises and the charitable nature of official develop-

ment assistance.

Yet, perhaps the idea that adaptation and development all

but overlap will help governments keep in mind the truth

of Lord Nicholas Stern’s statement that: “Development and

climate change are the central problems of the 21st century.

If the world fails on either, it will fail on both. Climate

change undermines development. No deal on climate

change that stalls development will succeed.”

3

After visiting developing countries in Asia, Africa, and

Latin America – and in each case visiting villages and rural

areas – the Commission concluded that while climate

impacts may be huge, they will be experienced locally, by

individuals, families and villages. It is at this level that adap-

tive capacities and resilience must be increased.

This does not in any way decrease the role of the

national government; in fact it suggests that national

governments must be much better at connecting with

remote areas and peoples. Examples of how this is being

done are apparent in the partnerships with non-govern-

mental organizations (NGOs) and UN organizations.

There is also an alarming tendency in some countries

for national governments to decentralize responsibili-

ties to local communities – for running things like the

schools and health clinics – without decentralizing the

funds to do so, or seeing to it that local leaders were

trained for the tasks. This tendency increases, rather

than decreases, vulnerability.

Yet the instinct to rely on local people is correct, for

they have been managing climate variability for centuries

and have much pertinent knowledge and many necessary

skills. The Commission found that part of the Bolivian

government’s integrated response to climate change

involves systematically gathering material on the tradi-

tional strategies the country’s various different cultural

groups have used in coping with climate variability.

Development with risk management

Once one begins to see adaptation as development with

risk management, and view the development process from

a local angle, one can see how the various sectors of the

development process will need to be managed differently.

Take energy. No nation has developed economically

without increasing access to modern energy services.

Yet, energy access issues tend to be separated from

climate mitigation and adaptation issues.

Recent research has shown that the burning of biofu-

els such as firewood, crop residues and dung may be

more damaging to the climate than using a ‘modern’

carbon-based fuel like liquefied petroleum gas (LPG).

LPG is also healthier in that it causes less indoor air

pollution, its use does not tax forests or other ecosys-

tems and it does not have to be laboriously gathered and

hauled. Some governments have successfully encour-

aged shifts from firewood to LPG.

In terms of water management, systems need to be

improved at all administration levels. At the regional

level the focus should be on defining transboundary

patterns never seen before: too little rain one year, too much the

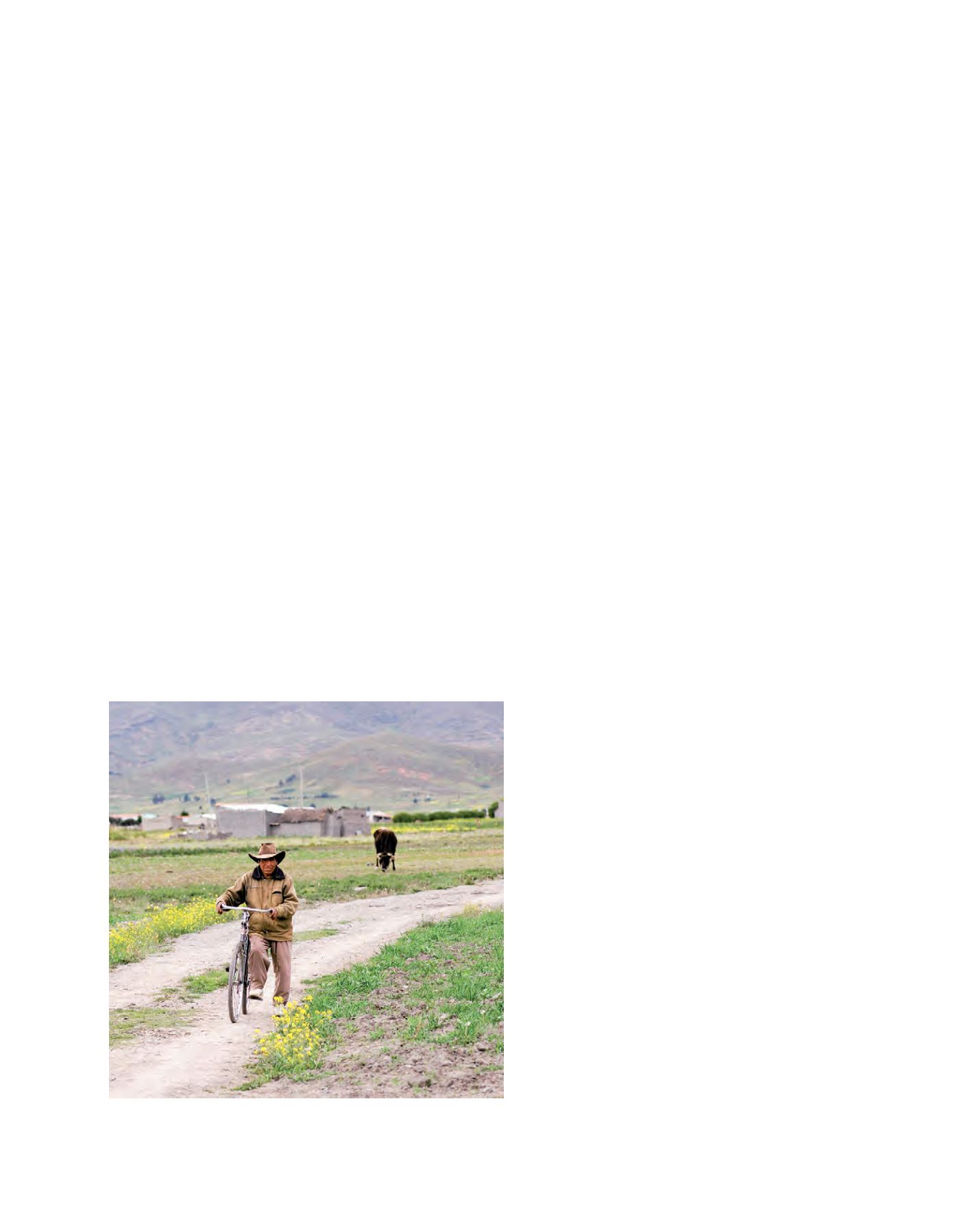

next. The Samoan fisherman sails on less predictable seas. The high-

land Bolivian farmer is threatened by malaria for the first time in

recorded human history.

Uncertainty increases vulnerability, especially for those whose

lives depend directly on natural systems. They need new software in

the forms of education, data and knowledge. They need democratic

governance and political voices to articulate views and concerns.

They need effective local governments connected to national govern-

ments. They need markets that work for them so that they can trade

and build their assets to tide them through illness, bad harvests and

the smaller, local disasters that they are experiencing more of.

In short, they need development, but of a new kind that manages

risks. For it is development that decreases vulnerability, and decreas-

ing vulnerability to climate change decreases vulnerability to other

threats such as high prices for food and energy.

The adaptation development overlap

The conclusion that adaptation equals development, but a more

complicated kind of development, is messy for many reasons.

Firstly, it suggests that ‘development plus adaptation’ calculations

will never give precise answers. Secondly, the development process

is challenged by multiple crises and is having trouble reaching the

poor, the food-insecure and those without access to modern forms

of energy; so making it more complex does not inspire confidence.

Thirdly, the development community and the disaster risk reduction

community operate in separate silos. That separation is becoming

rapidly more damaging. Fourthly, the conclusion is almost ‘politically

incorrect’ in that developing countries want the wealthier countries

to honour the UNFCCC and help them with adaptation costs; they

see this not as charity but as a debt, a reparation, owed to them by

the nations that developed on the basis of carbon emissions. They do

The highland Bolivian farmer is threatened by malaria for the first time in recorded

human history

Image: Vassil Anastasov