[

] 115

ers, the authorities and environmental NGOs, in stark contrast to

the conflicts that earlier arose in Finland in relation to compul-

sory conservation programmes such as Natura 2000. Forest owners

particularly appreciate the chance to maintain their property rights

while receiving fair compensation for their participation in conser-

vation initiatives.

The METSO programme for 2008-2016 is based on an earlier pilot

programme that gained the backing of stakeholders ranging from

landowners’ associations to environmental NGOs. The new Finnish

government plans to spend 40-50 million euros annually to enable

the METSO programme to protect forest biodiversity and support

related research work. The programme’s groundbreaking approach

to forest protection has attracted interest in other countries where

social acceptability represents a potential barrier to nature conserva-

tion schemes.

Protecting state-owned forests

The METSO programme finances measures to protect and enhance

biodiversity in state-owned forests administered by Metsähallitus.

This government agency operates as a commercial forestry concern

while also striving to conserve nature and provide free recreational

facilities in state-owned lands, including Finland’s 36 national parks.

Metsähallitus recently issued new environmental forestry guide-

lines to be followed in state-owned forests. Produced through

collaboration with WWF Finland, the guidelines emphasize meas-

ures to safeguard ecosystem services, including biodiversity, carbon

sequestration, nutrient cycles, water protection, flood prevention

and recreational amenity values, as well as the production of wood

and other forest products.

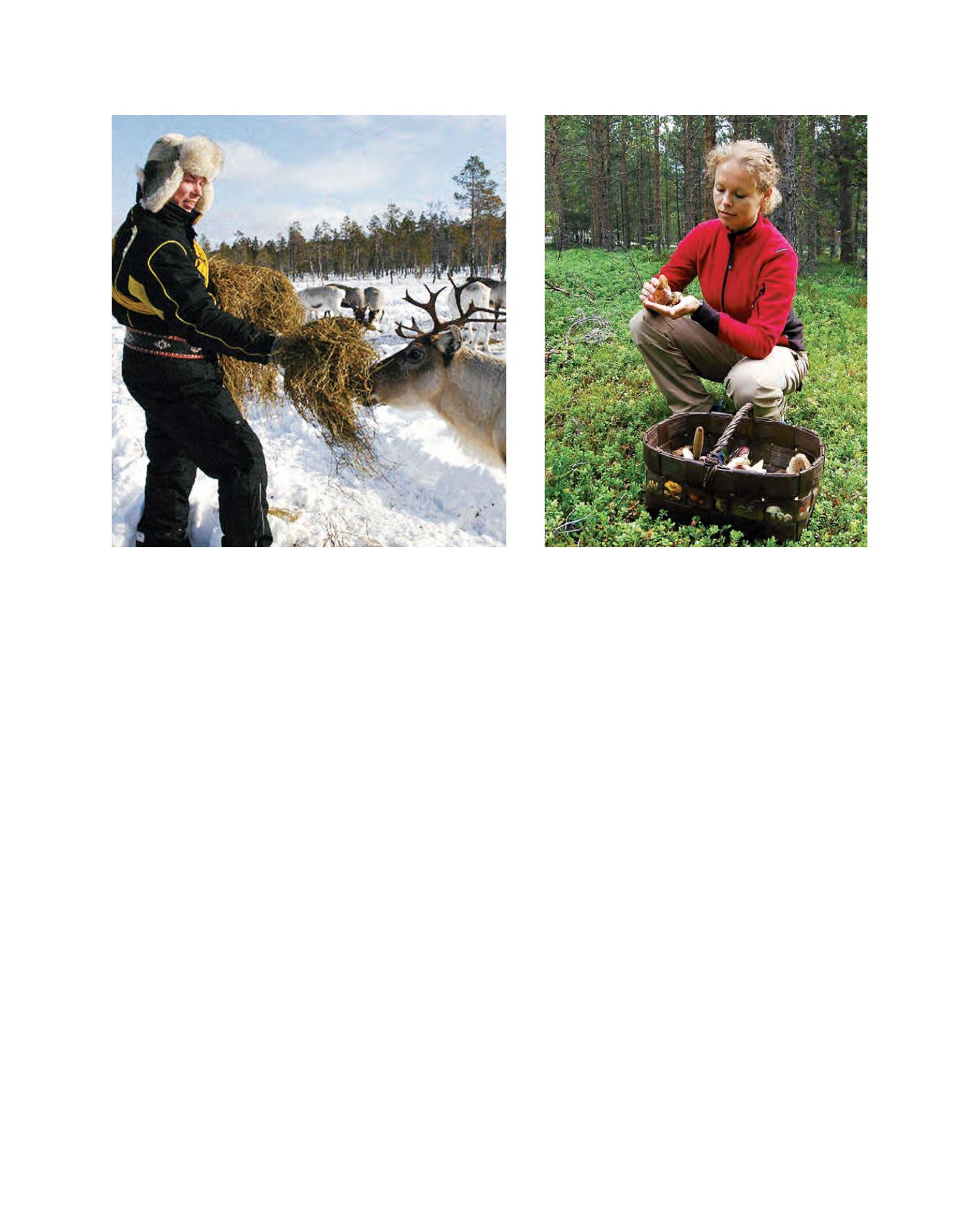

In the Inari region of Finnish Lapland, Metsähallitus

recently resolved a serious conflict by defining new

logging limits acceptable to environmental NGOs and

associations of reindeer-herders, whose animals require

mature forests for winter grazing.

A favourable future

One important indicator of the sustainability of forest

management across Finland is the fact that 95 per

cent of the country’s commercially managed forests

are independently certified under the PEFC Finland

scheme. The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) forest

certification scheme, preferred by many NGOs, is also

beginning to gain ground.

The State of Finland’s Forests 2011 report attests that

‘The state of Finland’s forests has improved over the

past 20 years. Forests, forest bioproducts and ecosystem

services are estimated to continue to form an impor-

tant part of Finland’s national economy in preparing to

alleviate the impact of climate change and to produce

well-being services for citizens’. This report is based on

Finland’s national criteria and indicators for sustainable

forest management, which are in turn derived from the

Forest Europe process.

Finland’s growing forests will undoubtedly play

a crucial role in efforts to achieve Finland’s longer-

term strategic policy goal of building a socially,

economically and ecologically sustainable bioecon-

omy by 2050.

Petri Mattus’s reindeer graze freely in forests near Inari in Finnish Lapland during

the winter. Finland’s forest policies are shaped to ensure the preservation of the

traditional reindeer-herding livelihood of the Sámi, Europe’s only indigenous people

Finns readily take advantage of their legal right of access to all

forests for recreational purposes such as harvesting natural products

including wild berries and mushrooms

Image: Hernan Patiño

Image: Kare Liimatainen