[

] 117

assets like land, forests or other natural resources, their

traditional interconnection with stock markets can only

be dissolved in the medium term.

Despite the wait for greater funds to flow into forests

outside the US, the question remains whether forest

ownership or land lease in developing countries by

international investors is a threat or a benefit. Brazil for

example, in its efforts to slow land-grabbing, recently

released a law that complicates land ownership by

foreigners. African and Asian countries, where owner-

ship is even disputed between governments and local

people, need to come up with implementable concepts

for conflict solution. A 2011 study by FAO pointed

out that legal security is of the utmost importance to

investors. The opportunity to attract investments may

further contribute to legal transparency and security in

recipient countries.

Investment in timberland can be through direct

investments by investors themselves. More likely

however, is the strategy to channel funds through

highly specialized investment managers, in the US

generally called Timberland Investment Management

Organizations (TIMOs). Hancock Timber Resource

Group for example, a large US-based TIMO, holds

assets in forestry of around US$9 billion in the United

States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Brazil

(December 2010), and recently acquired a 200,000

hectares plantation licence in Australia. Similarly,

an extremely low level (now around 30 per cent) and after the war,

reparation payments were partly made with timber.

Compared to the long coexistence and co-development of forests

and people, the forest investment industry is very young.

2

Only

recently, about 20 years ago, have forests been subject to an industry

that purchases, manages and sells forest properties at a commercial

and business scale. Market participants are pension funds, endow-

ments, foundations, insurance companies and high net worth

family offices, so-called institutional investors. These are investing

increasing financial resources in forests and forestry activities. It

is estimated that around US$50 billion

3

worth of forests are held

by those institutional investors, most of which (80 per cent) are

in the United States. Figures on the global market size are vague,

however estimates suggest it to be in the vicinity of US$300 billion

4

to US$467 billion.

5

The trend to invest in forestry outside the US is

strong and KPMG suggests that major areas of interest are emerging

markets in Brazil and New Zealand (over 50 per cent of investors).

Australia, Chile, China, India, Malaysia, Russia and South Africa

attract attention (between 15 and 50 per cent of investors), whereas

Uruguay, Indonesia and Viet Nam receive less attention (less than

33 per cent together).

The gap between potential and actual market size is wide. Many

countries in the developing world expect an influx of funds into

their forestry businesses and prepare for this by providing politi-

cal opportunities and taking care of financial and legal stability.

However, the time between sourcing investments and beneficiaries

is long and volatile global financial markets are not likely to shorten

this. Although institutional investors increasingly tend to prefer real

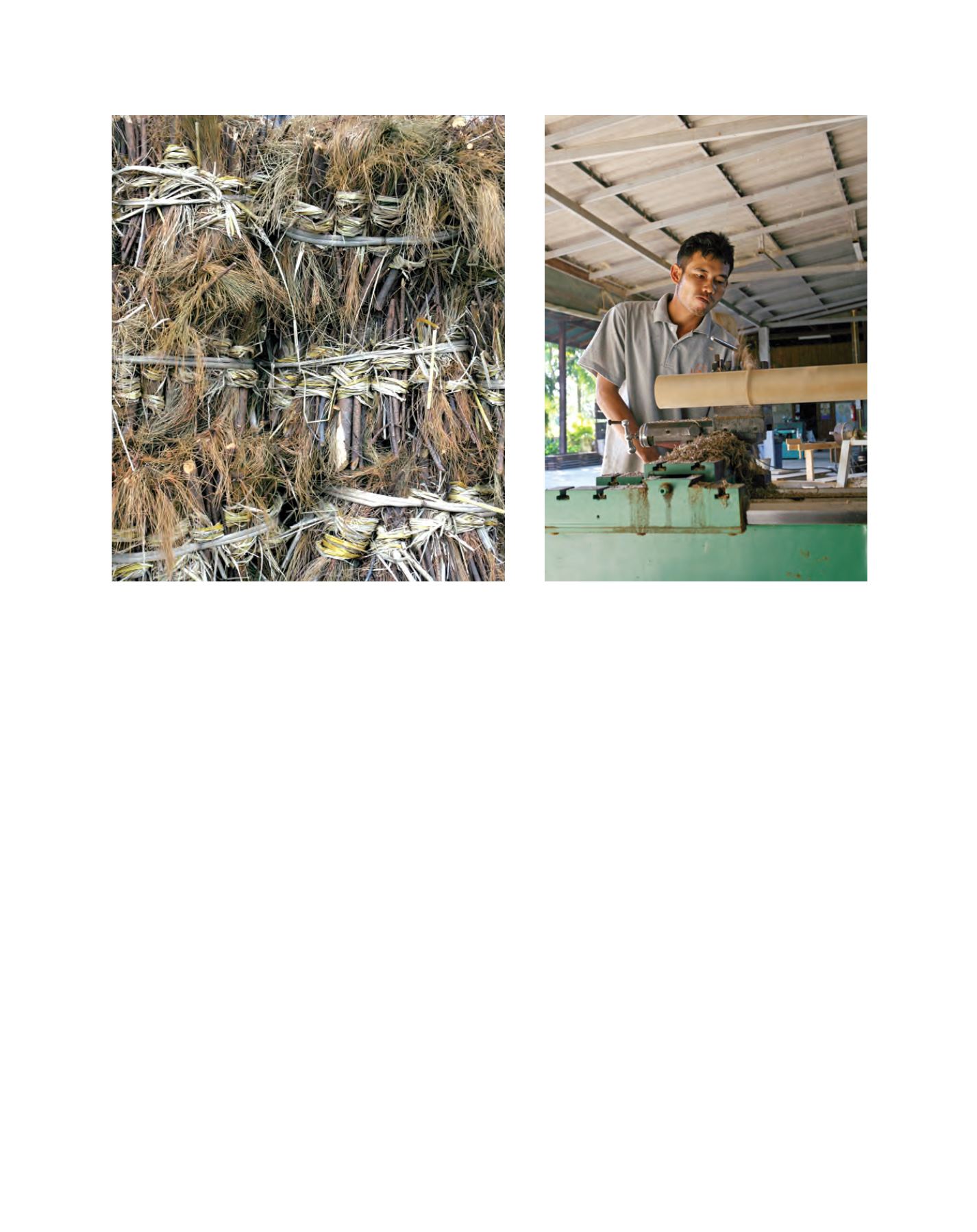

Residual timber, here small branches and needles from pines in China, contributes

to energy supply (China)

Investments in downstream processing combine traditional handicrafts

skills with new technology (Teak processing in Thailand)

Image: R. Glauner

Image: R. Glauner