[

] 118

the International Woodland Company in Denmark holds US$2.5

billion under management, distributed to the US (45 per cent),

South America (33 per cent), Oceania (10 per cent), Europe (8 per

cent) and new markets (4 per cent). The latter figure shows the

level of funds flowing into these markets. However, 4 per cent of

a total of US$50 billion equals US$2 billion. Compared to the vast

available areas in developing countries, this is a drop in the ocean.

Forest investments have one dominant objective: commercial

and competitive production of timber for sawn wood or pulp for

local and international markets. While investments in conifers

prevail in northern countries,

eucalypts

, pines, teak, and

acacias

are common in the south. Investment horizons rarely exceed ten

years and commonly lie at minimum around US$10 million for

one deal. Besides those funds channelled through investment

managers in US$10 million parcels, there is a growing number of

smaller projects, where private individuals buy land or shares of

companies that plant trees at a much smaller scale. Particularly

in Europe, a vast number of these providers offer investments in

trees, mainly high-value plantations. Teak dominates the market,

as timber prices rise steadily.

6

Marketing costs however are high

and due at the beginning of the investment period and trees have

to produce interest on them over timespans of up to twenty years.

Thus, there are not only success stories but also failures. Investors

lost considerable amounts because projects were short of mainte-

nance costs for subsequent years after planting and had to be sold

cheaply, or investors had to pump in additional money.

Does money from forest investors actually reach the people on the

ground? Does it contribute to social development and parity in rural

areas? And is the approach of investing in forestry on a

commercial basis sustainable?

There are many positive examples but also exceptions

to those. However, in general, positive answers can be

given to all these questions. A study by FAO has revealed

that sustainability is a major concern to the forestry

investment community. They might not be primarily

concerned with two of three pillars of sustainability, the

social and environmental aspects, but the third pillar,

economic, is their field of expertise. And there is one

common lesson learned in many development projects:

without sustainable economics, other values such as

social and environmental benefits cannot be sustained.

Forest investment projects create monetary value in

rural areas, where it did not previously exist before.

The sustainable management of a natural forest signifi-

cantly contributes to forest conservation in many terms,

including area, biodiversity and environmental services.

Employment is created in rural areas and people receive

training and education, as many commercial projects

see a tremendous benefit in having literate and educated

staff. Rural schools and health stations normally follow

the first wave of development, when forest workers bring

their families to settlements around forest camps and

saw mills. The establishment of planted forests equally

contributes to rural development. Forest plantations

are often established in formerly deforested grassland

areas, which are of only marginal monetary benefit

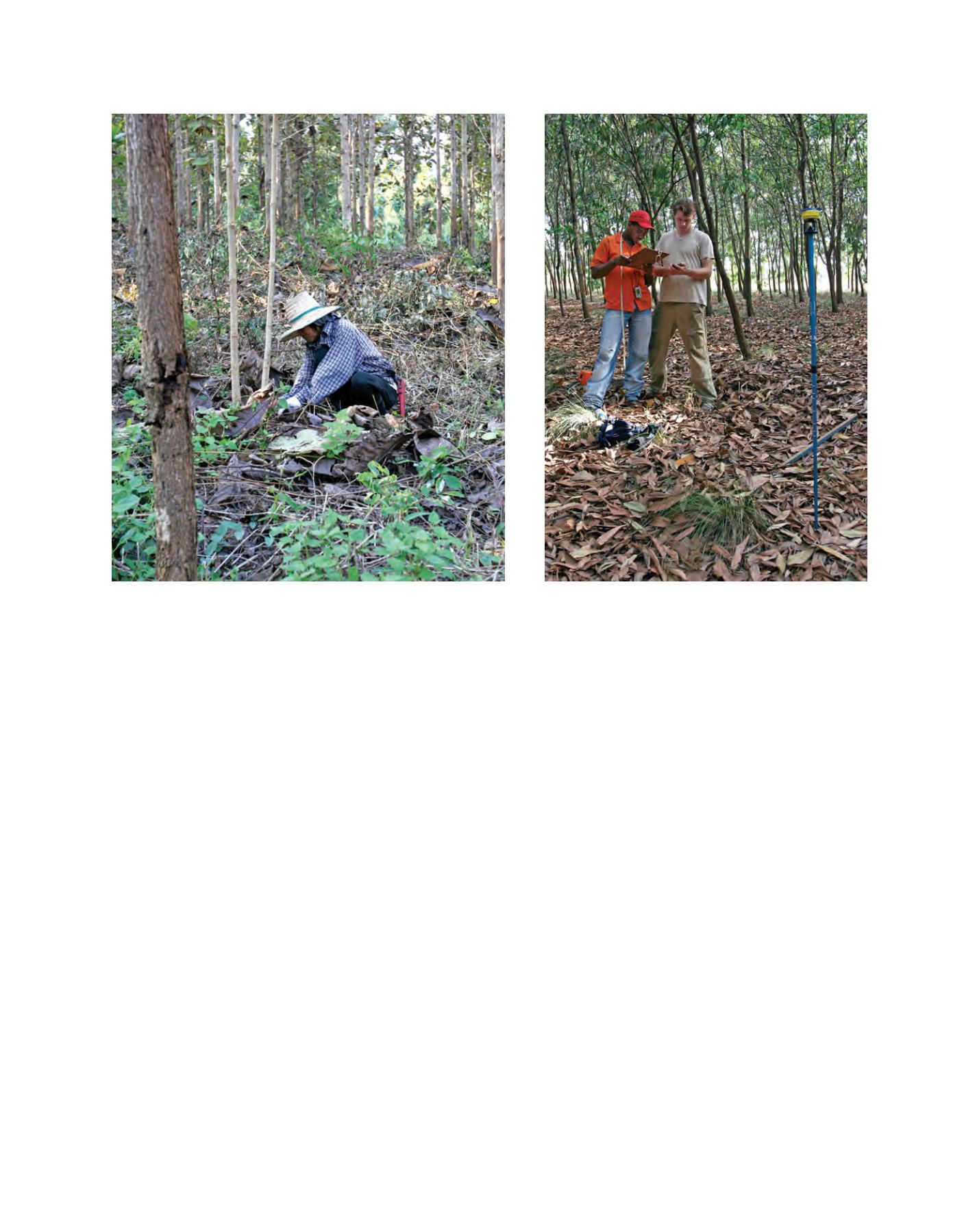

Weeding forest plantations is creating jobs, particularly for rural women as seen in a

teak forest in Thailand

Forest investments are ideal training grounds for local and

foreign student (Brazil)

Image: R. Glauner

Image: R. Glauner