[

] 125

A national forest programme

run for people and by people

José M. Solano, Head of Forest Planning and Management,

Ministry of Environment and Rural and Marine Affairs, Spain

A

s a consequence of the great changes that Spain experi-

enced after the introduction of the 1978 Constitution, its

national forest policy was revised. Spain had a consider-

able number of international commitments associated with the

Resolutions of the Ministerial Conferences for the Protection

of Forests in Europe (now Forest Europe), in addition to those

arising from joining the European Union in 1986. Spain was

also involved in environmental United Nations forums that

grew out of the Río de Janeiro Summit, including the Forest

Principles and related Intergovernmental Panel on Forests (IPF)

and Intergovernmental Forum on Forests (IFF) proposals for

action on biodiversity, climate and desertification.

The Spanish forest sector was maturing, with more private compa-

nies and mechanization on the rise. Consciousness-raising about the

value of the environment and the public’s support for protection of

natural resources resulted in high demand on the forests for a large

variety of goods and services. Under these conditions, there was a

need for a less interventionist forest policy.

The new national governance structure that accom-

panied the 1978 Constitution resulted in Spain moving

from being one of the most centralized countries

in Europe to one of the least. The 17 Autonomous

Governments are competent in forest management,

leaving on the national level the coordination of forest

policies, national level planning and international rela-

tions in this sector. A lengthy process to transfer public

forest management, materials and human resources to

the new regional governments ended in 1985.

The National Forest Service started the process of

defining a new forest policy for Spain that would take

into account the new conditions and also allow for a

phenomenon new to Spain: public participation. The

decision was taken to phase in the changes, starting with

a general consensus resulting in a binding Spanish Forest

Strategy document that would allow the later inclusion of

a Spanish Forest Plan and also a new Forest Law.

Strategy for sustainability

The value of the Spanish Forest Strategy is that it

was intended from the beginning to reflect a national

consensus among all actors related to forests. The

process started in 1996, but at that time there were diffi-

culties concerning public participation, as the former

political system did not allow for public participation.

There were not even lists of stakeholders available,

giving the planning team the long and tedious job of

identifying relevant individuals and organizations.

When a new stakeholder was contacted, other pros-

pects were often introduced. As a result of this process,

after some months a list of more than 900 stakeholders

was available.

While the Spanish pulp, paper, particle and fibreboard

industries had strong and well-structured associations,

less capital-intensive businesses such as saw mills and

furniture manufacturers were mainly very small and

often family-run, with a very low degree of organiza-

tion. There were some forest owners’ associations, but

the many small, mostly local or regional associations

were unable to speak with one voice. Professionals

were very weakly united and trade unions were not well

represented. Environmentalists worked with two main

groups of international origin (Greenpeace and WWF)

but there were thousands of small local and special-

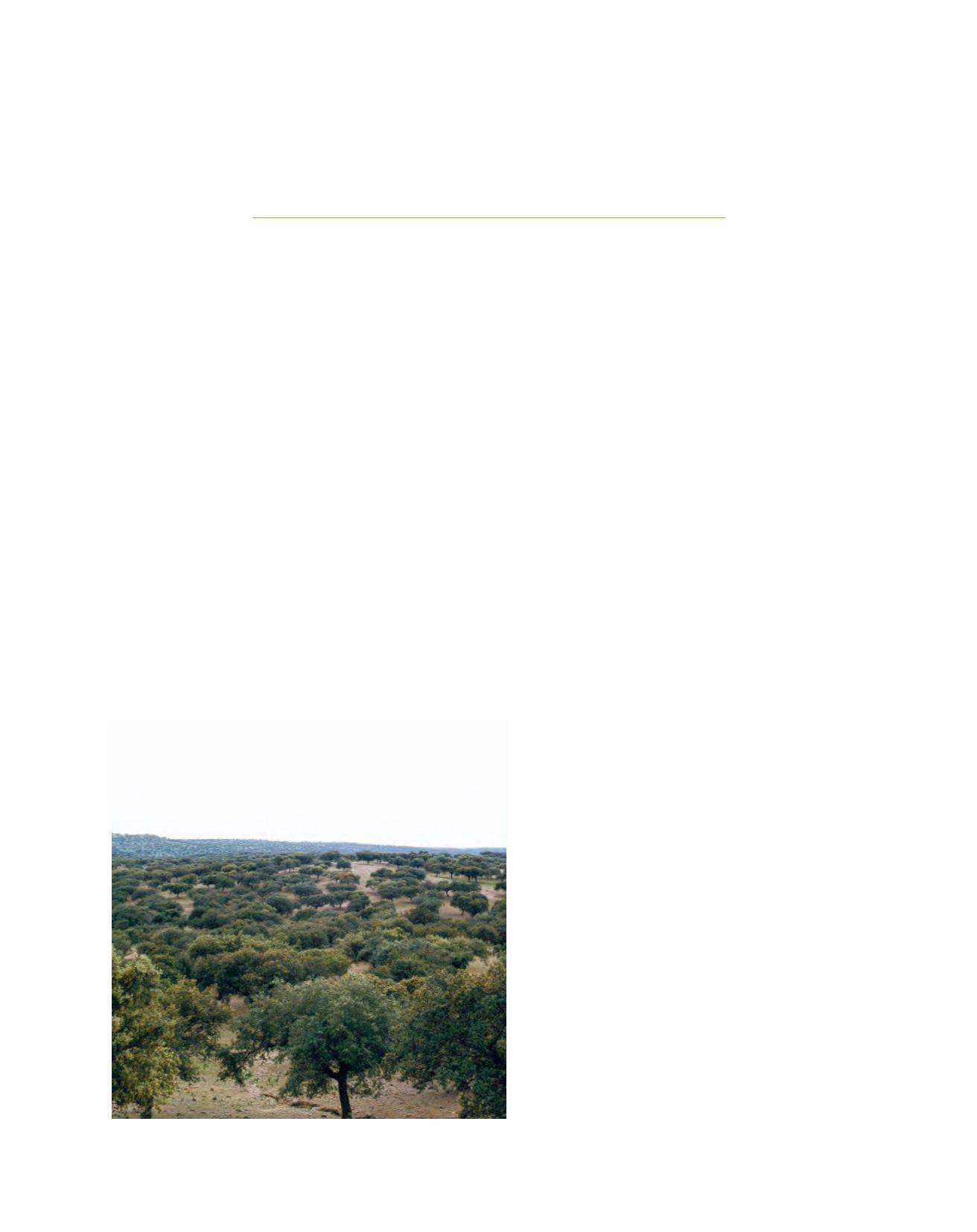

Dehesa, a typical Mediterranean forest

Image: BDN