[

] 126

challenges for Spanish forests and also for the asso-

ciated economic sector. It also presents a vision for

forests in Spain and outlines long-term objectives

although it only briefly touches on how and when

these problems should be solved.

But the real benefit of this process was not so much

the final document as the changes in the sector that have

been driven by it. There has been very fluid communica-

tion among stakeholders and governmental institutions,

based on mutual confidence that has facilitated later work.

Communication with other governmental departments

has commenced and in particular, the relationship with

regional forest services has improved substantially. The

spirit today is that we all have a common objective and

must cooperate to reach it. Another effect was the restruc-

turing of the forest sector. New and larger associations

have been created and today there are unique counterparts

for almost every cluster of the sector. Finally, the model

of participation has changed, as all stakeholders agreed

on the need for an institutionalized participation council.

As immediate and practical consequences of the

Strategy, we can mention new tax legislation for forests

that is more favourable for owners. Also, the creation

by Royal Decree of the National Council of Forests is a

major step forward. A national standard for sustainable

forest management was approved and Spanish versions of

the Resolutions of Forests Europe and the Mediterranean

Forests Management Declaration were published.

A plan for sustainability of forests

The Spanish Forest Plan was drafted following the estab-

lishment of the Strategy. It formed part of the electoral

ized groups forming almost daily. Another problem was that there

was no institution that could represent the rural and forest-based

municipalities. Some organizations were not able to sit at the same

table with others, or tended to flag old issues independent of what

was on the meeting agenda.

All these circumstances led to the development of a completely

new system to achieve consensus. Firstly all known stakeholders

were divided into three groups: administrative organizations such as

ministries, regional forest services and municipalities. Sector groups

included forest owners, communal forest associations, industries,

contractors, importers, retailers and other economic actors. All the

others were integrated in a social group, including forest profes-

sionals, education and training institutions, research institutions,

environmentalists, consumers and trade unions.

A first draft was discussed in the three groups and all those

attending were asked to give their comments in writing. During the

process, many of those involved in the first round, particularly from

the social group, felt it was not relevant to their institutions, so they

abandoned the process.

A new draft was generated, reflecting most of stakeholders’

requirements. There were eight concrete issues on which opinions

were divergent. To find solutions for these issues, antagonists sat at

the same table for the first time. Groups were formulated to include

at least three participants – to avoid ‘one against one’ situations –

and with a clear focus on the issues to be discussed.

Finally, the last two or three paragraphs on which differing opin-

ions existed were resolved in a special meeting of dissenting parties

with a strong facilitator, and the text was drafted. The Strategy was

finally born two years after its inception and was presented to the

public by the Minister of Environment at the beginning of 2000.

The Strategy document provides an overview of forests and the

forest sector, analysing and explaining the main problems and

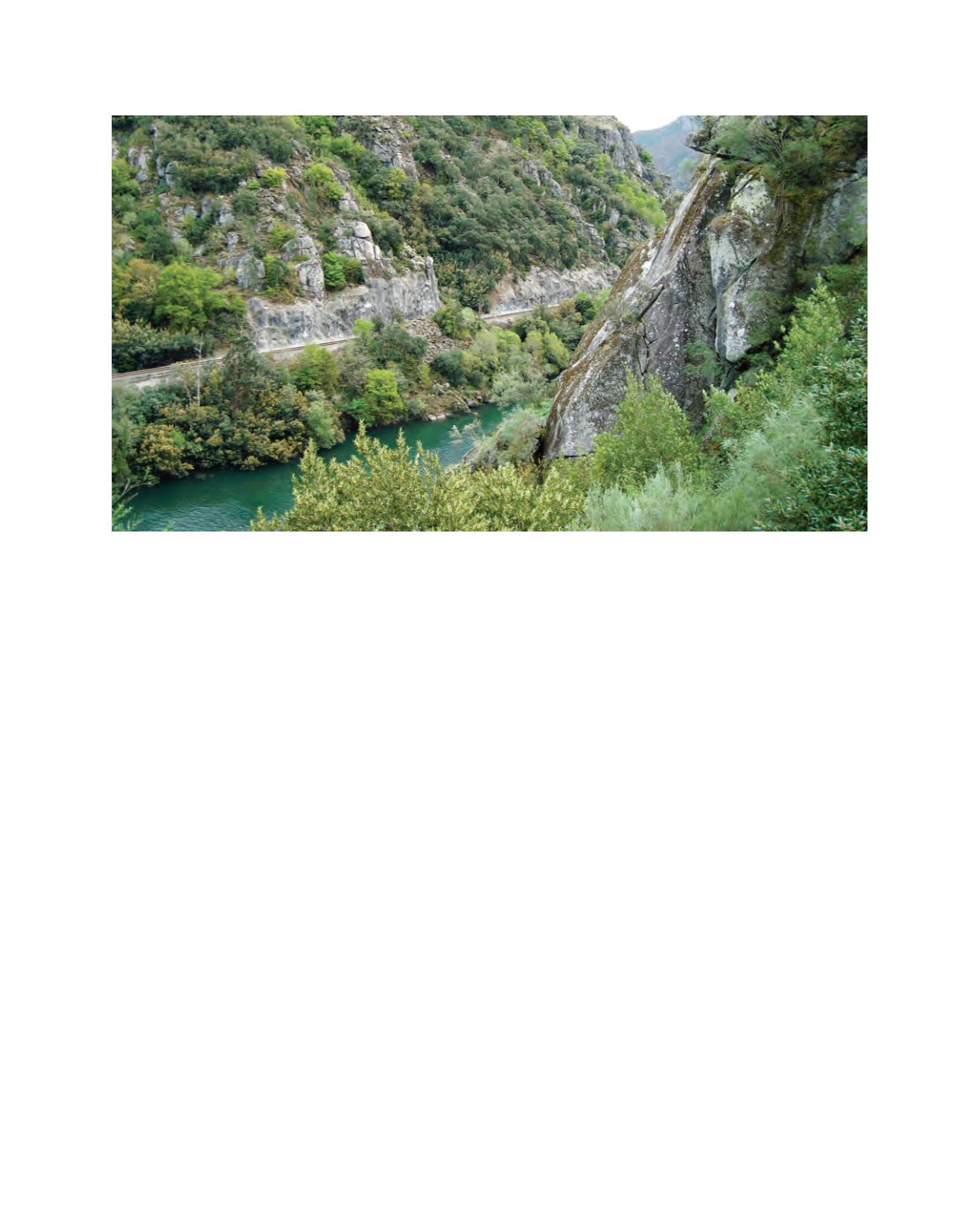

Water and forest interaction

Image: BDN