[

] 127

programme with which the Government won the general election of

2000, so a very strong direction was applied from the political level to

the planning team. Finally a draft was presented to the 64 members of

the National Forest Council in its first meeting in January 2002. This

participatory institution included all the parties mentioned above.

From 30 papers received while drafting the plan, 581 concrete

statements were extracted and organized in a database, of which

40 were general statements on issues not covered by the plan. A

further 312 were accepted for inclusion in the draft, while 119

were rejected, either because they did not fall within the scope of

a national planning instrument or because they did not fit in with

the spirit of the Strategy. The remaining 110 allegations were tabled

for discussion in a Council meeting, which considered three issues:

how the policy should deal with privately owned forests, matters

regarding production and productivity and the cost and budget of

the Plan itself. Debates on these issues took place in two sessions,

and after formal approval by the Council and by the coordination

system with the regional governments, the Government gave its

formal approval to the Spanish Forest Plan at the beginning of July.

This planning was considered flexible enough to allow regional poli-

cies to be developed, while setting common objectives for all of them

in an inclusive manner, demonstrating equity and proportionality to

foster cohesion between territories.

A legal framework for sustainability

The existing Spanish forest legislation dating back to 1957 was

retained as the basis for a new and more political act. A draft of the

new law was updated while changes were made to the Forest Plan,

as its main purpose was to translate the elements of the Plan into

legal language.

A draft of the new Forests Act was provided on 9 January 2003 to

the members of the National Forest Council and on this occasion

43 comments were received, with more than 1,200

questions raised about the legal text. The process

tested with the Plan was repeated, trying to address as

many of these issues as possible. Two more drafts were

discussed, with many compromise solutions suggested.

Finally, on 24 February, with 37 votes for, 3 against

and 10 abstentions, the Council approved the final

text. The entire process took only 6 weeks.

The final text was immediately sent to the

Government, which, following legal consultations,

approved it as ‘legislative project’ on 21 March –World

Forest Day – and sent it to Parliament. It was modified

in both legislative chambers and finally signed by the

King on 21 November. In a fitting finale to this crucial

piece of legislation, it was the last act approved in the

legislature before Parliament was dissolved.

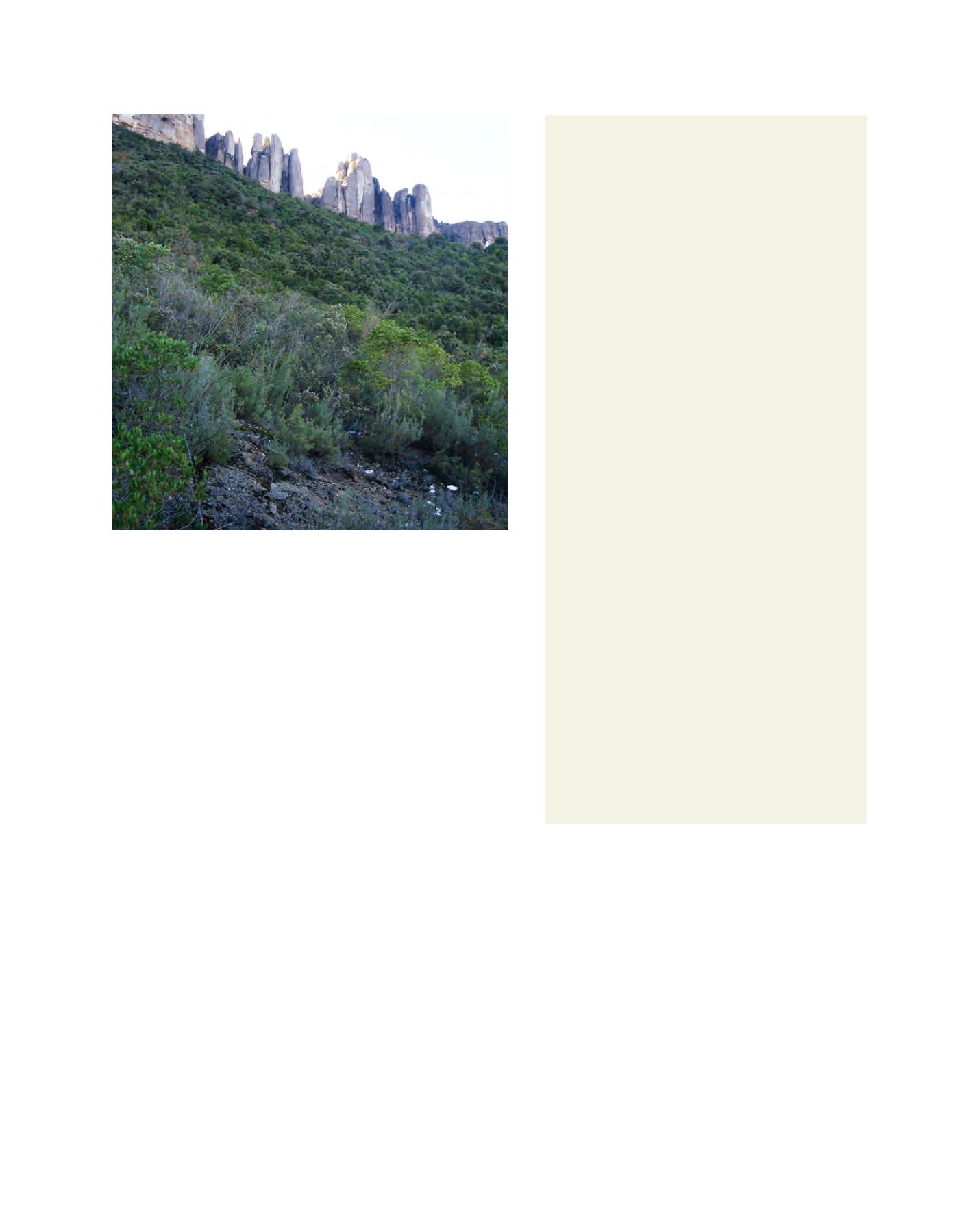

In Spain there are some forests with no trees

Image: BDN

The example of Navarra

In the Foral Community of Navarra in Northern Spain, 64

per cent of the million hectares of land consists of forests,

with 24 per cent growth in the last 20 years. As in the rest

of Spain, this region experiences high climatic diversity, so

it is well suited to pilot projects.

The Forest Service in Navarra decided to modify the

legal scheme for forest planning that was in force in

the rest of Spain and to create a system more suited

to its own forests. The methodology for elaboration of

planning documents was radically changed, including

all uses, resources and values of the forest, analysing

their compatibilities and setting different objectives for

each part of the tree-covered areas, shrub areas and

pastures. In addition, requirements for habitat and species

conservation were integrated.

Relationships among trees, cattle, protected species

and other resources and values were integrated in the

planning instrument with a view to creating a more flexible

planning system to ensure natural regeneration. There was

also a substantial decrease in the price of the instrument

itself and an increase in its potential to be applied to

smaller forests.

At the same time, procedures for the active participation

of owners (mainly municipalities) were set in place, making

them more involved in forest planning, improving tender

procedures by demanding applicants have knowledge

of the territory and its conditions and that they work in

multidisciplinary teams. This resulted in the creation of

local technical teams that today continue advising forest

owners on technical matters.

During these years, there have been continuous

updates to the scheme, both as a consequence of its

implementation and due to emerging situations, such as

those related to forest certification. Nowadays indicators

of sustainability for the two main certification schemes

present in Spain (Programme for the Endorsement of

Forest Certification and Forest Stewardship Council)

are included in the planning instruments, allowing the

owner voluntarily to join either or both of them. Simpler

instruments have also been introduced for small privately

owned forests.

As a consequence, today more than 60 per cent of

forest land benefits from a planning instrument (the

average in Spain is about 12 per cent) and 43 per cent is

certified, with 84 per cent of regional timber being certified.

It must be said that these figures reflect true management

as the Forest Service verifies the data, which are accepted

by all those involved.