[

] 305

I

nternational

C

ooperation

on

W

ater

S

ciences

and

R

esearch

ties have resulted in a decline in some river gauging

station networks, while concerns about misuse of

data, commercial drivers, political sensitivities about

transboundary resources and an overarching lack of

understanding about the value of river flow informa-

tion limit the exchange of the hydrological data that

is collected. The 5th World Water Forum in 2009

concluded that, as a result, many operational water

managers lack adequate information to inform deci-

sion-making.

Scientific researchers also lack sufficient observa-

tional evidence, with a 2010 paper by Hannah and

others noting that large-scale international archives of

water data are insufficiently populated in some areas

of the world.

1

Freshwater environments, their drivers,

controls and impacts are not constrained by national

boundaries and hence international cooperation is

vital to provide the information needed to further our

understanding of hydrological systems. Such problems

are ever more acute in the light of increasing global

concerns surrounding hydrological variability.

observations of river flow, the integrated output of all environmental

processes and human interactions occurring within a catchment.

Observational information on river flows underpins informed deci-

sion-making in areas such as flood risk estimation, water resources

management, hydro-ecological assessment and hydropower genera-

tion. Policy decisions across almost every sector of social, economic

and environmental development are driven by the analysis of this fresh-

water information. In light of this widespread importance, such data has

assumed a high political prominence in some areas of the world, with

accurate information on the state of water resources crucial to avoid-

ing and resolving conflicts between individuals, organizations and even

states. Its wide ranging utility, coupled with escalating analytical capa-

bilities and information dissemination methods, has resulted in a rapid

growth in demand for such data over the early years of the twenty-first

century and this trend looks set to continue in the near future.

Recognition of the fundamental importance of observational fresh-

water data led to a growth in river monitoring networks in many

parts of the world in the second half of the twentieth century. More

recently, developments in hydrometry (the science of water measure-

ment) and the widespread adoption of digital recording coupled with

the growth of information technologies, in particular the development

of the Internet, have provided the tools for more efficient data collec-

tion and exchange. At the same time, escalating analytical capabilities

and a heightened awareness of the changing environment have further

increased the demand for access to such information.

In spite of recent developments, however, the availability of

hydrometric information continues to constrain both research

and operational hydrology across the globe. The third edition of

the United Nations

World Water Development Report

(WWDR3)

highlighted that “worldwide, water observation networks provide

incomplete and incompatible data on water quantity and quality

for managing water resources and predicting future needs.”

Globally, funding constraints and changing governmental priori-

Case study: UK National River Flow Archive

The National River Flow Archive is a publically funded

focal centre for hydrometric information storage,

analysis and dissemination.

2

It provides access to river

flow data and associated information, and knowledge,

advice and decision support on a range of hydrological

issues. The archive serves a wide user community

incorporating water management professionals,

scientific researchers, educational users, government

bodies and international organizations.

Under the UK’s distributed model for delivering

hydrological services, river flows are monitored

across a dense network of gauging stations by four

separate bodies with responsibilities to different areas

of government. Their mandates include monitoring

network installation and upkeep, data collection, data

processing and initial data validation. Following this,

data are provided at regular intervals to the National

River Flow Archive, maintained by the Centre for

Ecology and Hydrology. Here, they undergo secondary

validation before being combined with auxiliary

information and added to the national archive for long-

term storage and dissemination.

While the archive exists in a separate organizational

structure to the major national and regional hydrometric

measuring authorities, it is delivered through close

collaboration between stakeholders including the

scientific research community, other data analysts,

policymakers and national government. This cooperation

is rooted in the long-standing need to assess water

resources across the United Kingdom as a whole and

recognition that river flow information collected in one

area of the country is valuable in managing freshwater

issues in other hydrologically similar catchments

which may be geographically and politically removed.

Industry-standard regionalization methodologies have

been developed to predict river flow characteristics

at locations where they are not monitored, through

extrapolation in space from locations where data is

available. By pooling data across organizations, regions

and countries, the UK is able to better estimate river

flows at ungauged sites and manage the risks posed by

hydrological extremes.

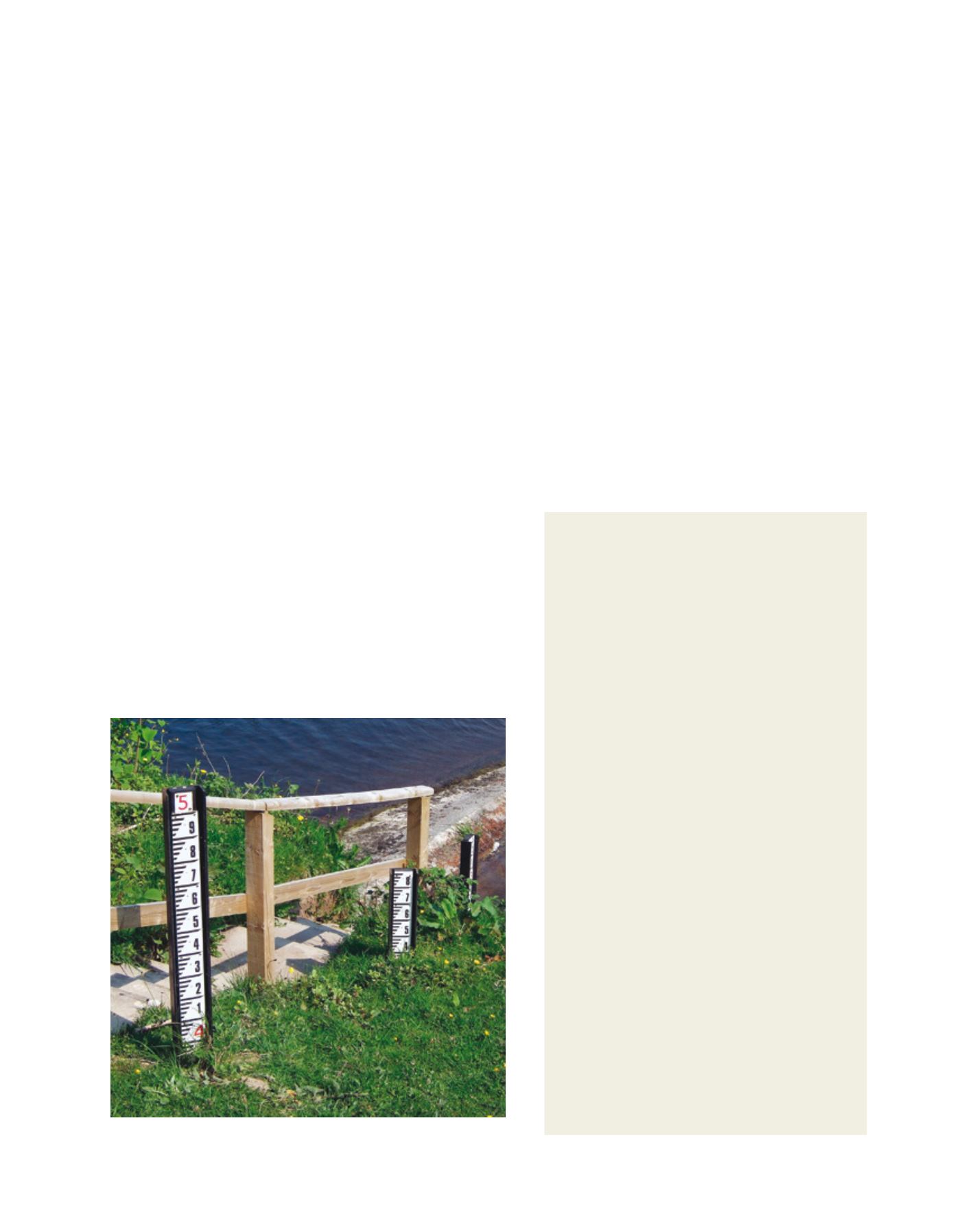

A river monitoring station on the River Tywi in South Wales, UK

Image: UK National River Flow Archive