[

] 104

tunities were further enhanced through support to Farmer

Interest Groups (FIGs) as a means of increasing access to

production and marketing services. The FIGs now operate as

a federation, with technical support provided through a CSO

known as the Central Himalayan Environment Association.

The project also engaged scientific institutions to address

specific needs for knowledge-generation, monitoring and

assessment of interventions, and quantification of environ-

ment and development benefits. A key example is the Energy

and Resource Institute (TERI), which served as a partner for

baseline and final impact assessment for the project. TERI

was involved in developing a sampling framework, designing

questionnaires, field testing, pilot surveys, refining question-

naires, field surveys, data cleaning and entry and, finally, data

compilation and aggregation.

As part of internal monitoring, the progress of the annual

works programme was monitored on a monthly basis through

a Monthly Progress Report generated at the divisional level and

consolidated at WMD level. Monitoring teams were consti-

tuted with members drawn from various technical wings of

the directorate who regularly visited the project area. Random

field visits, monthly meetings, checklists, brainstorming, amid

all stakeholders at district level at monthly intervals and at

regional level on a half-yearly basis, was an integral part of the

internal monitoring. At the district level there was a District

Level Governing Committee for monitoring and supervision

of the project and at the state level there was a State Steering

Committee with representatives from concerned line depart-

ments and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). The

State Steering Committee reviewed the project progress at

half-yearly and annual intervals, and periodic field visits were

undertaken by senior government and project officers.

Participatory monitoring and evaluation with community

members was introduced to ensure stakeholder participation,

with full involvement of GP-level teams, which include repre-

sentatives from all stakeholder groups at GP level. The project

placed special emphasis on ‘social auditing’, which ensured

transparency, accountability and openness with full involve-

ment of the communities. In keeping with these principles

there was widespread disclosure of information through wall

writings, awareness-generation campaigns, radio programmes

and publications. Finally, the use of information technology

(IT) was an integral part of the project from formulation, plan-

ning and database management to monitoring of the project’s

physical and financial progress and impact assessments.

Management information system software was developed as

an endeavour to use IT for management of information.

The global environment benefits (GEBs) of SLEM in

Uttarakhand are largely associated with the following inter-

ventions at watershed, sub-watershed and micro-watershed

scale: improving soil and water conservation, reducing erosion

and siltation, sustainable use of forest resources (non-timber

forest products), and introducing alternative energy sources.

The GEBs from the interventions include forest protection

(contributing to biodiversity conservation and sustainable

flow of water resources), improvements in soil carbon and

reductions in greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation.

The participatory approach for planning and implementation

of interventions with communities ensures that GEBs are

generated in the context of addressing drivers of degradation.

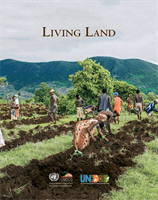

Pine briquetting reduces dependency on fuelwood collection by women as well as reducing deforestation and greenhouse gas emissions

Images: Patrizia Cocca/GEF

L

iving

L

and