[

] 105

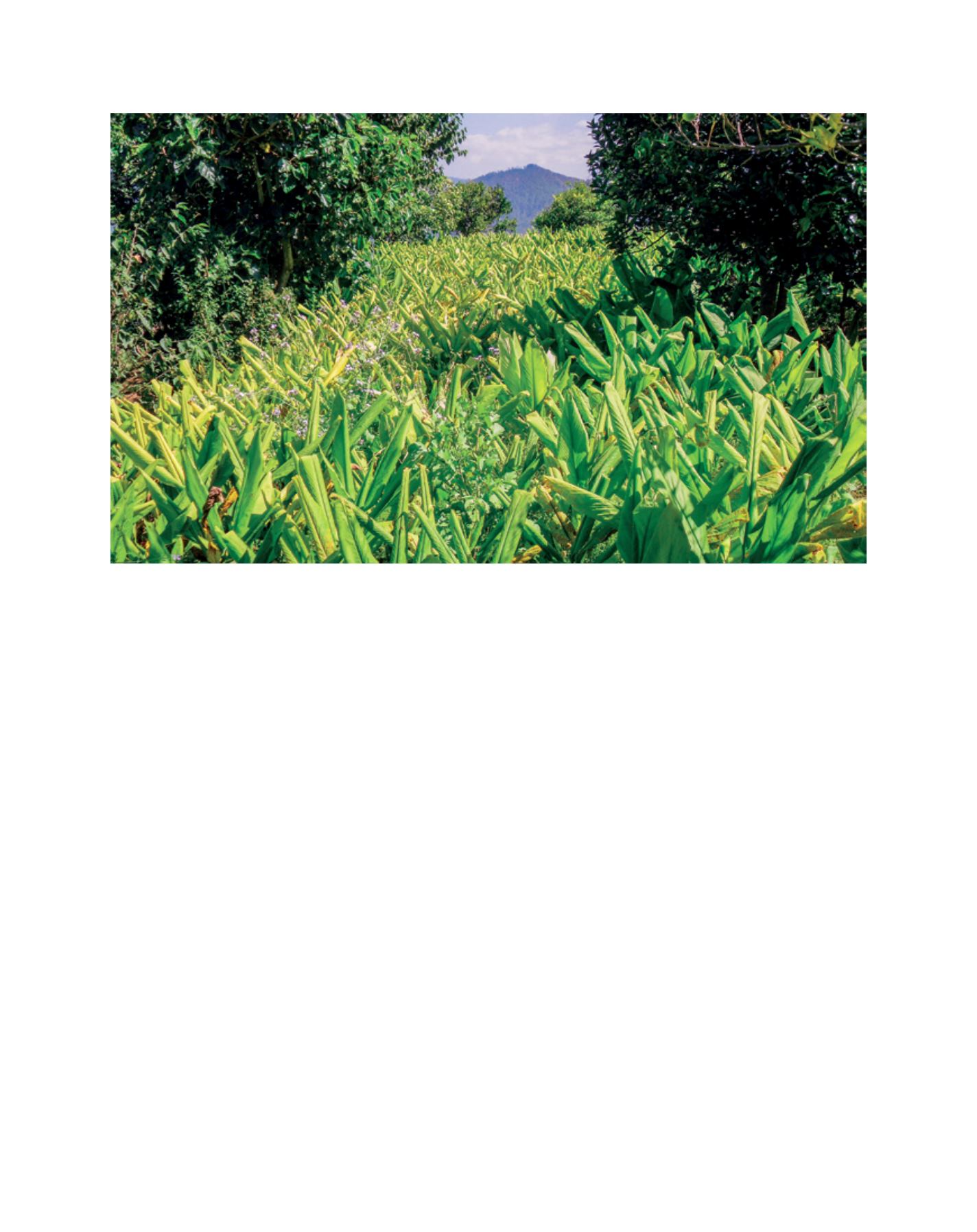

Improvements in land and water resources provide opportunities for income generation through high-value crops such as turmeric

Image: Patrizia Cocca/GEF

As a result, overall functioning of the watershed ecosystem is

at the heart of the SLEM in Uttarakhand, which also ensures

long-term sustainability of the project outcomes.

The project also demonstrates how GEBs are linked directly

to interventions for improving livelihoods and creating options

at local level. For example, pine briquetting reduces depend-

ency on fuelwood collection by women, which in turn reduces

deforestation and greenhouse gas emissions. Furthermore,

the reduced felling of trees for fuelwood protects the fragile

slopes, contributes to biodiversity conservation and helps to

increase flow of water. Therefore, socially and economically

empowering communities by putting them at the centre of

soil conservation has also led to the creation of global envi-

ronmental benefits. With respect to the monitoring of GEBs,

the focus was mainly on silt loading in drainage lines in repre-

sentative streams using a turbidity meter and discharge and

durability of flow for water sources based on time series meas-

ures, and climate change mitigation (carbon benefits were also

determined from estimating emissions avoided through alter-

native energy intervention such as biogas, water mill and pine

briquetting). Biodiversity benefits were much less established

and derived only from vegetation surveys in the watershed

and areas of forest protected by communities.

Knowledge activities were implemented at different levels

and reflect the importance of linking scientific and traditional

sources. Traditional knowledge was taken into account during

the planning phase and fully harnessed by the implementation

team through consultations with communities and surveys.

Knowledge-sharing also flowed from the implementing team

and NGOs involved in the project to the beneficiaries, with

the dissemination of information and knowledge about new

techniques and methodologies to harness and preserve water

resources, increase and diversify agricultural productivity and

create alternative livelihoods. A Farmer Field School was also

established with the cooperation of one of the farmers as a hub

for training and knowledge-sharing.

Lessons learned and best practices applied within the

project were shared with other government agencies, part-

ners and donors as a means of facilitating up-scaling beyond

the project areas. The manuals, methodologies, community

resource maps, watershed work plans, video documentaries

and documentation of lessons learned from the project will be

invaluable for informing the design of other IEM projects and

for informing policy transformations to support the integrated

approach at state and national level.

By mobilizing technical experts from various line depart-

ments in the state, the project presented opportunities for

the alignment of interventions and outcomes with the invest-

ment priorities of those departments. This will ensure that the

project outcomes are integrated into future plans of the line

ministries, and that links between environment and develop-

ment needs in the watersheds are maintained in the long term.

A state government order introduced at end of the project

reinforced this convergence, in addition to oversight of the

project assets created during implementation. At the level

of individual micro-watersheds, the communities assumed

full ownership of all assets created to improve ecosystem

functions. The communities also signed memoranda of under-

standing with the WMD for operation and maintenance of

the assets.

L

iving

L

and