[

] 173

Due to increasing population growth and unsustain-

able land uses, arable lands are shrinking. Currently, each

human has only 0.22 hectares at their disposal; in 1960, that

figure was 0.5 hectares. The other major constraint to food

production is the development of soil salinity in irrigated

agricultural farms which is great concern as 40 per cent of

world food is produced from irrigated agriculture and 60

per cent from rain-fed agriculture. Currently, an estimated

20 per cent of irrigated lands is salinized to various degrees

and the global annual cost of salt-induced land degradation

in irrigated areas could be US$27.3 billion because of lost

crop production.

2

Globally about 1.6 million hectares are

lost annually due to salinization. With this pace of loss, the

irrigated area that is now contributing to agricultural foods

will be out of production in nearly 140 years — an alarming

situation since by 2050 we have to produce 70 per cent more

food to feed 2 billion extra mouths in addition to current 7.3

billion. The impact of climate change is another constraint to

achieve sustainability in food security. An Intergovernmental

Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) synthesis report

3

has

recognized the major impacts of climate change as food and

water shortages, increased displacement of people, increased

poverty and coastal flooding.

Overexploitation has shrunk arable lands for food

production and it may not be able to provide sufficient food

to meet human demand. Globally there are 1,500 million ha

cropland including 250 million ha (17 per cent) irrigated

producing 40 per cent of world food, and 1,250 million

ha (83 per cent) rain-fed agriculture contributing 60 per

cent of world food production.

4

Under a business-as-usual

scenario, by 2050 agricultural production must increase by

60 per cent globally — and almost 100 per cent in develop-

ing countries — to meet food demand alone for 9 billion.

1

To achieve such targets it is essential to understand soil

health constraints and develop problem-solving, innova-

tive ways which have long-term effects. This requires the

development and implementation of new agricultural and

food policies, and water, environmental and soil protec-

tion plans. The concept of climate-Smart Agriculture

(CSA) could be a step in the right direction. The CSA

being promoted by FAO

5

is not a single specific agricul-

tural technology or practice that can be universally applied.

It is an approach that requires site-specific assessments to

identify suitable agricultural production technologies and

practices. With this understanding, using innovative ways

to improve soil health, intensification in both irrigated and

rain-fed agriculture may be possible. However, increasing

agriculture lands may not be a viable option in many coun-

tries due to various factors including unfavourable terrains,

such as in African countries.

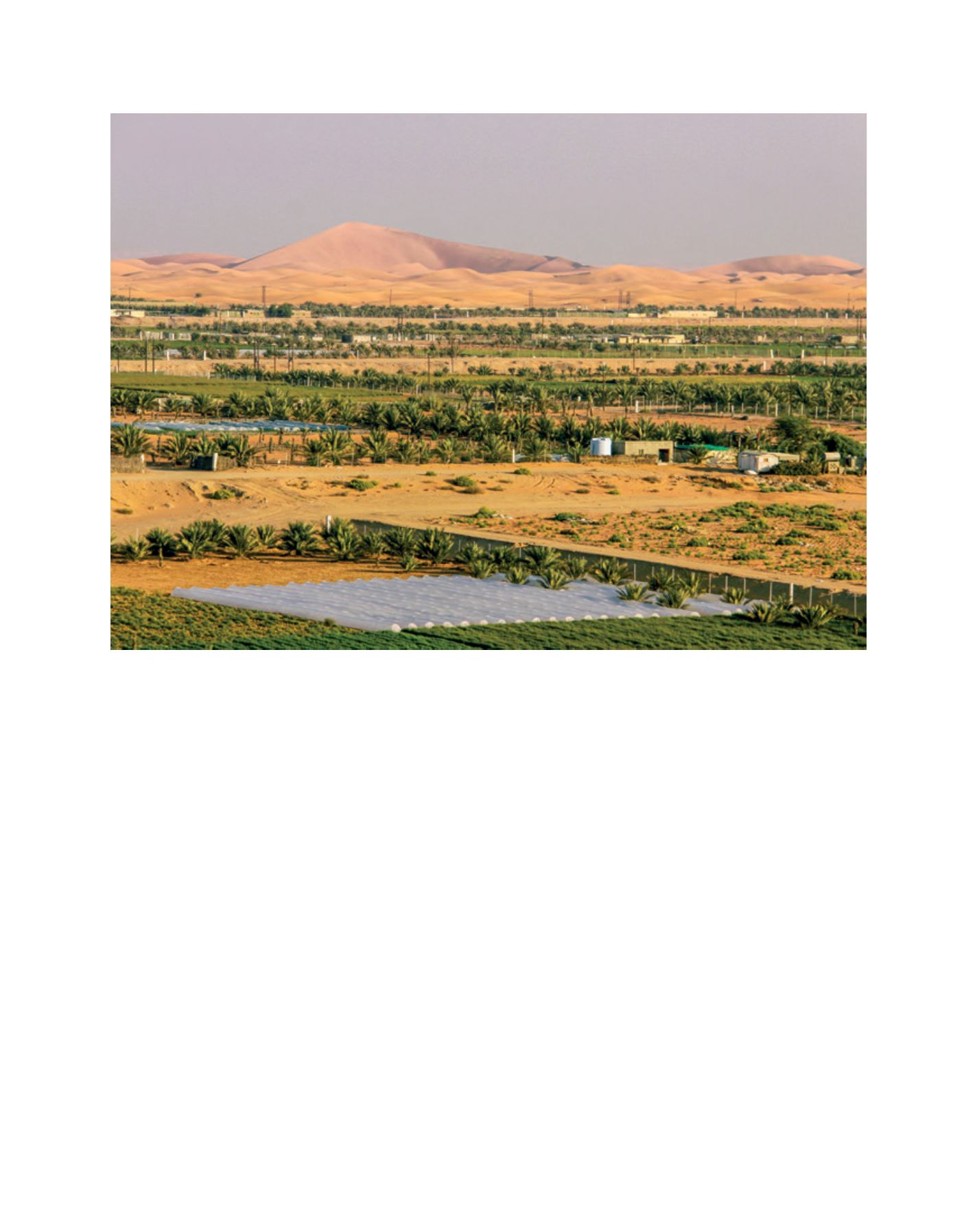

ICBA has experience in managing marginal lands with sandy, salt-affected soils through scientific and site-specific diagnostics

Image: ICBA

L

iving

L

and