[

] 21

ished in peasant farmland) and awareness of the limitation

of water withdrawals has increased. However, no correc-

tions have been introduced to address these changes.

Water resources management challenges have increased

significantly in the past two decades. Continuing popula-

tion growth and rising incomes have led to greater water

consumption as well as more waste. Rural populations in

developing countries are growing dramatically, generating

demand well beyond the capacity of already inadequate

water and sanitation infrastructure and services and food

security. Overcoming these issues requires more effective

and integrated, intersectoral water management, enhanced

capacity at all levels and better welfare for rural people.

It is the view of many development agencies that even very

sophisticated water management technologies at all levels of

the system will not solve the water supply problem without

increasing water use efficiency in the field. Better water use

efficiency is described as increasing the yield while maintaining

existing water application. Every cubic metre of water saved in

the field (when efficiency of the irrigation network is 50-60 per

cent) reduces the need for water delivery by 50 per cent without

any reconstruction of the canal network. However, efficiency

of furrow irrigation is also affected by several external factors:

• poorly levelled field surfaces

• fluctuations of water supply flow during irrigation

• use of non-optimal irrigation technique elements that do

not correspond to specific natural conditions

• lack of interest among land users in using improved

methods of irrigation

• lack of a real cost for water delivery.

In addition to these factors, irrigation quality still depends

on the availability of water in the right quantity and at the

right time. Areas with water supplied through irrigation

systems are better supplied, while areas with pumped water

often suffer from delayed water supply due to pump capac-

ity or insufficient electricity.

Several lessons have been learned, with potential for

wider applicability. For example, the implementation of

advanced irrigation technologies (more efficient sprinkler,

drip and micro-irrigation systems) can be used in the most

arid regions.

In order to be able to invest to advanced irrigation tech-

nologies, cropping patterns should be changed from field

crops (such as cotton, alfalfa, rice, wheat) to high value

crops such as trees, fruits, nuts and vegetables. The produc-

tion value and market values of field crops are lower than

those of high value crops, while the water use and acreage

is much higher.

In addition to generating improved farm incomes, peren-

nial crops require year-round maintenance and tend to

provide stable employment at higher wages. Spring and

fall vegetable crops, although seasonal, are labour-intensive

and generate strong on-farm revenues that support regional

economic growth.

In particular, water management institutions play an

important role in their interaction with farmers to intro-

duce different programmes at local level. Low-interest loans

or microfinance programmes have been created to enable

farmers to change from traditional irrigation methods to

advanced irrigation technologies.

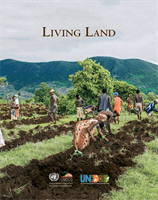

Investment in the Chókwè irrigation facilities has improved the socioeconomic status of more than 5,000 smallholder farmers

Images: IDB

L

iving

L

and