[

] 24

were ineffective, hence the need to aggregate and build

institutions of the poor from the grass-roots level. The insti-

tutional platform of smallholder farmers created a local

source of finance and organization that the rural poor need

to start enterprises, gain job skills, increase incomes and

try innovative solutions to their problems — including food

security and nutrition centres.

Key lessons were learned during the project. Rural credit

programmes, particularly in remote areas, require innovative

mechanisms that adapt to constraints on financial institutions

and beneficiaries. Following the success of SLCDD Phase 1,

the Government of Sierra Leone was strongly committed to

the CDD approach and requested a follow-on project, SLCDD

Phase 2, which has been processed and approved by IDB’s

Board of Executive Directors. In June 2015 a financing agree-

ment was signed by IDB and the Government at the IDB

Annual Meeting in Mozambique. SLCDD Phase 2 will scale up

on the results of SLCDD Phase 1. It relies on demand-driven

investments and the empowerment of local communities to

improve productivity and is specifically focusing on technol-

ogy improvement, enabling SAGs to leverage collaboration

between project and research and extension systems and

improve the quality of livelihoods.

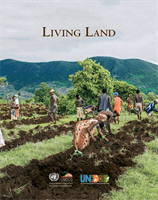

Ensuring sustainable rural livelihoods in Cameroon

Cameroon’s poverty rate remains at 20-25 per cent and is a

disproportionately rural phenomenon. With limited irriga-

tion potential, natural resource management (NRM) issues

are critical to sustainable economic development, especially in

more marginalized rural areas such as the Mont Bpabit region.

The rural poor, who make up 85 per cent of the popula-

tion in the area, rely on rain-fed agriculture and herding. Given

that the population in this area is expected to increase by more

than 20 per cent between 2012 and 2020, the sustainability

of such livelihood systems is in question. The Government of

Cameroon has sought to maximize agricultural potential in

dryland areas while managing natural resources in a sustain-

able manner, but there have been several problems as the tribes

and agricultural producer organizations have tended to remain

isolated, and the Government has had little experience address-

ing these rural concerns.

The development objective of the IDB-funded Rural Land

Development Project was to help reduce rural poverty and

improve food security in the Mont Bpabit region through the

development of 1,200 ha of lowlands, and improvement of

agricultural production and NRM. The project components

were designed to achieve this objective through lowland

development and construction of socioeconomic infrastruc-

ture; water harvesting and watershed management, which

would introduce several environmentally-sound water-

harvesting interventions; adaptive research implemented on

a demand-driven basis; and extension and training, which

would provide funding for establishing effective agricultural

extension services.

All activities are implemented within the framework of

traditional community-based structures/tribal organiza-

tions, resulting in a demand-driven development process.

This tribal framework ensures that government personnel

become sensitized to rural community needs and concerns

and it mobilizes local populations to manage natural

resources in a sustainable manner. To incorporate tribal

systems into their management framework, community

groups which determined their own composition and struc-

ture were established.

With the objective of conserving the natural resource

base, 1.2 million cubic metres of water storage facilities

have been constructed, exceeding the estimated target by

about five times and representing a 45 per cent increase in

water availability. The project also established 150 rangeland

management units, and established fodder trees and shrubs

on approximately 2,000 ha. In terms of poverty reduction

and improving livelihoods, construction of safe drinking

water storage facilities resulted in agricultural and health

benefits for the local rural population. Increased fodder

availability and genetic improvement led to increased income

from livestock and the adoption of high-yield varieties led

to increases of 27-70 per cent in the productivity of vegeta-

bles and other crops. Overall, socioeconomic conditions of

10,440 households have been improved. In addition, the

project built a good foundation for local capacity in resource

management through training and support for project staff,

farmers and community representatives.

Engaging an isolated group in a broad NRM project

through the incorporation of existing community-based

institutions was an innovative approach. Core project

beneficiaries include farmers — especially SFs, farmers’ asso-

ciations, cooperatives, rural producer organizations (RPOs),

private sector and value chain actors at the local, district and

national level. Overall, these RPOs represent about 10,000

farming households, of which 1,200 produce cassava, 2,050

produce maize, 3,000 produce vegetables and 4,000 produce

rain-fed upland and lowland rice.

The project illustrates that a multisectoral/multidiscipli-

nary approach in NRM and poverty reduction projects is

more likely to achieve objectives than single-sector projects.

Participatory project implementation requires flexible budget-

ing that is not constrained to predetermine outputs, but relies

on a demand-driven identification of activities. And adequate

initial training and capacity-building is a prerequisite to the

start-up of activities requiring beneficiary participation.

Future direction for smallholder farmers

The question serious analysts would pose is: which sectors

of the economy in Sierra Leone and Cameroon need urgent

attention? Agriculture is the motor of the economy and is

therefore a priority. There is also the issue of illegal migra-

tion, which sees African youth migrating to Europe only

to perish in the Mediterranean. This is of concern to their

countries of origin as well as recipient countries. In order to

make agriculture attractive to the youth, there is an urgent

need to invest in activities that are likely to create employ-

ment; to invest massively in labour-intensive infrastructure

projects and transform agriculture from subsistence-based

production to business; and to reform the land tenure

system and improve farming practices. Agriculture has to

be a rewarding business. Not only will this automatically

earn rural farmers more money, but it will also make agri-

business a more viable proposition.

L

iving

L

and