[

] 54

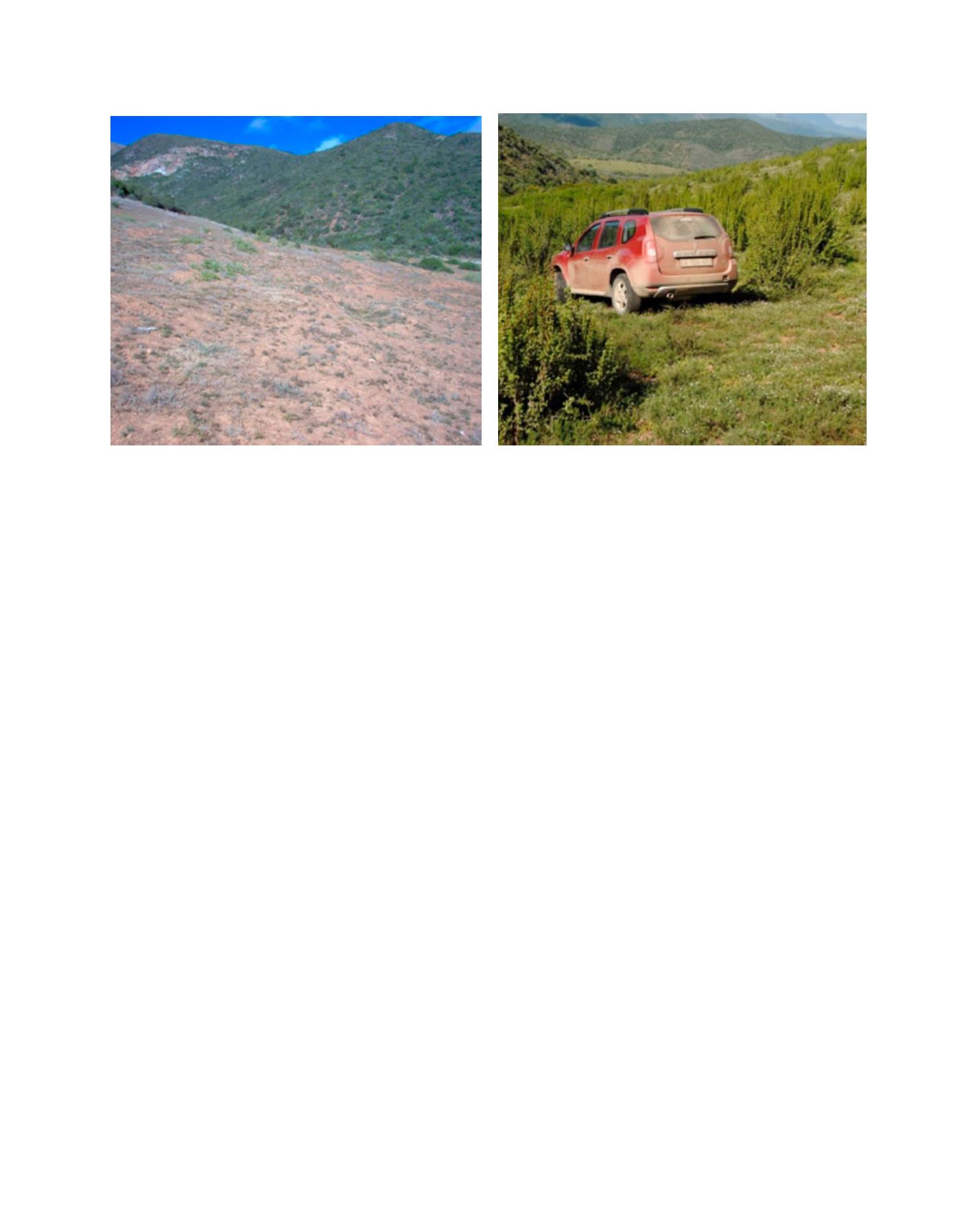

Image: Mike Powell (left), Christo Marais (right)

mean annual run-off with a high of 8.4 per cent in the Southern

Cape. The catchments with the highest impacts all fall within the

Maloti-Drakensberg range, the ‘water tower’ of South Africa that

supplies water to KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng Provinces, and the

Southern and Eastern Cape mountain ranges that supply water

to the Nelson Mandela Metropole (Port Elizabeth), the economic

hub of the Eastern Cape, the Garden Route (one of the country’s

ecotourism draw-cards), the catchment areas of Cape Town and

the wine lands in the Western Cape.

5,6

Not all the water used by

invasive alien plants is utilizable by humans though. In 2007 it

was estimated that invasive alien plants in high-yield catchments

and along riparian zones reduced usable water (registered water

use) by more than 4 per cent and if left unchecked this could

increase to more than 16 per cent. A water-scarce country like

South Africa simply cannot afford this.

7,8

Large-scale desertification is mainly caused by abandoned

croplands, overgrazing and unsustainable use of timber and

other fibre resources. Other contributing factors are unsustaina-

ble fire regimes — short fire return periods, burning during the

wrong season and then grazing the land too soon after the last

burn. These can all lead to major erosion, especially in the high-

yield catchments. Five of the country’s large dams have been

silted up by more than 60 per cent and the worst of them, the

Welbedacht dam, is silted up by more than 90 per cent.

9

Such

figures don’t represent the full picture, though, as many smaller

dams are also silted up but this information is not captured

in the national records. One such example is the municipal

dam of the small rural town of Mount Fletcher in the Eastern

Cape. The dam, which has a catchment of 77,100 hectares and a

storage capacity of 500,000 m

3

, was completed in 2008. Within

five years it was more than 80 per cent silted up.

From the above it is clear that not only does land degradation

have a major impact on water security, it also impacts negatively

on our ability to adapt to climate change. All climate change

models point to an increase in the intensity of both droughts

and floods, combined with extreme temperatures. South

Africa simply cannot afford not to invest in the restoration of

its ecological infrastructure. In the Eastern Cape Subtropical

Thicket Restoration Programme, of which more than 11,000

hectares is already under restoration, not only does restora-

tion have the potential to increase carbon capture by around

80-100 tons of above-ground and soil carbon per hectare, but

intact thicket also increases infiltration significantly.

10,11,12

Research has shown that more than 100 times lower infiltration

in soils associated with degraded thicket, relative to the soils

under intact vegetation, results in lower levels and less reten-

tion of soil moisture, almost double the amount of run-off and

an almost six-fold increase in sediment load.

13

The increased

run-off might sound positive but it all happens as part of flood

flows and leads to a reduction in dry season flows. Water-scarce

South Africa cannot afford to lose dry season flows.

At the moment it is estimated that the South African

Government invests around US$166 million per year overall, of

which the Natural ResourceManagement Programmes contribute

about US$147.6 million. In order to get on top of the challenge

though, the country will need to invest around US$1 billion per

year, adding around 100 000 jobs to the economy.

14

Footing such

a bill is unaffordable for the South African Government alone. All

enterprises depend on water and energy; it is therefore a logical

imperative that the private sector increases its commitment to the

restoration of the country’s ecological infrastructure and the deliv-

ery of ecosystem services. Once the private sector has internalized

the impacts of catchment degradation on profitability, sustainabil-

ity and risk reduction, investments in ecological restoration could

be absorbed into companies’ investment in enterprise and supplier

development. The restoration of ecological infrastructure not only

improves water security, contributing to economic growth and

livelihood security; it is also a critically important contribution to

managing climate change. To unlock resources the country will

need a legislative platform allowing for incentives to restore and

disincentives to degrade, backed up by appropriate institutions to

facilitate investments in ecological infrastructure.

The slope facing up the valley at the Cambria site (left) shows hardly any above-ground biomass in 2004; (right) the view of the slope from the top of the

valley in December 2014

L

iving

L

and