[

] 270

technology for future marine biological monitoring

systems.

The UN General Assembly has called for regular

Global Marine Assessments, and the Census intends that

its realm projects and OBIS will become standards for

these. Similarly, agencies around the world have called

for an ‘ecosystem approach’ to sustainable fisheries

management within their Exclusive Economic Zones.

What could be more important to managing an ecosys-

tem than knowing what lives there?

It is important to note that the Census has been

funded as a research programme. Long-term monitor-

ing of ocean biodiversity will depend on long-term

support within an operational GEOSS framework. By

emphasizing the societal benefits of global systematic

biodiversity measurements and associated data

systems, GEO can bring awareness at the ministerial

level of the green ocean and all life in the sea, and the

critical need for long-term stable funding for these

observations. At the same time, the breadth of GEO

will encourage collaborations among the Census and

related biodiversity programmes to identify and fill

remaining gaps so that the societal benefits of GEO can

be met.

Looking beyond 2010, the Intergovernmental

Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO has initiated

discussions with the Census to develop a strategy for

building a long-term biological monitoring programme.

Such a programme will eventually be an integral part of

GEOSS, and will provide it with the marine biodiversity

data essential to society’s needs.

is defining potential protected areas related to fish habitats, deep sea

corals and predator hotspots and helps to answer the question, ‘what

lives in the oceans?’ The ecosystem data collected through the Census

is being used, for example, to establish areas of reduced fishing in the

Northeast Atlantic. Coral reef information helps gauge the impacts

of rising temperatures and ocean acidity on this habitat. Studies of

past oceanic biodiversity and abundance provide information useful

for management on the status of stocks prior to or in early stages of

exploitation.

The ecosystems on shallower oceanic features such as seamounts

and hotspots, both of which have become targets for unregulated

over-exploitation, are also being studied by the Census. The UN

Convention on the Law of the Sea is still dealing with defining regu-

lations for the shallower parts of the open ocean. Census projects

are providing crucial information and technologies to recognize and

manage these ecosystems.

Forecasting what is likely to happen to ecosystems – what will

live in the oceans – is being carried out by a network of statisticians

and mathematical modellers. Models will focus on sampling design

and assimilate data in order to understand the transformation of

marine life in earlier times to present conditions, and to forecast the

likely future.

Climate

Marine life is sensitive to climate change over a wide range of lati-

tudes; the database developed through Census activities will

contribute to charting its response. The Census has research

programmes in both polar regions that will guide long-term biolog-

ical monitoring beyond the International Polar Year. The Census is

surveying the Southern Ocean to understand the biological diver-

sity of this unique and poorly understood environment. Global

warming is transforming the Arctic sea: the year-round ice realm may

cease to exist within the next 50 to 100 years. The Census includes

an international collaborative effort to inventory biodiversity in the

Arctic sea ice, water column and sea floor.

Status of the Census today; plans for the future

Having begun in 2000, the Census of Marine Life is now in its

seventh year of studying life in the sea. Each of the projects is mature

and providing new insights and information, and OBIS is collecting

and disseminating information as required. Because of its very nature,

this work must continue well beyond the end of currently planned

field and ocean realm projects.

The principal goal of the Census in 2010 is to have a representa-

tive record of global marine biodiversity patterns, available through

OBIS, that can be used to enable commercial, legal and conservation

interests to deal sustainably with ocean biodiversity. For example,

the data in OBIS is proving valuable as nations develop Marine

Protected Areas to preserve biodiversity and increase sustainability

of fisheries. In addition to this information, the Census will provide

legacies of proven technology and science input to management prin-

ciples and international cooperation. Especially important is the

legacy of demonstrating that a coordinated, multifaceted effort to

explore ocean biodiversity can make real inroads on this seemingly

overwhelming but vitally important task.

In 2010, the Census fieldwork will end and its first comprehensive

report on the status of knowledge of marine biodiversity will be

released, with a focus on integration, synthesis and visualization.

The work of the Census will have provided both the knowledge and

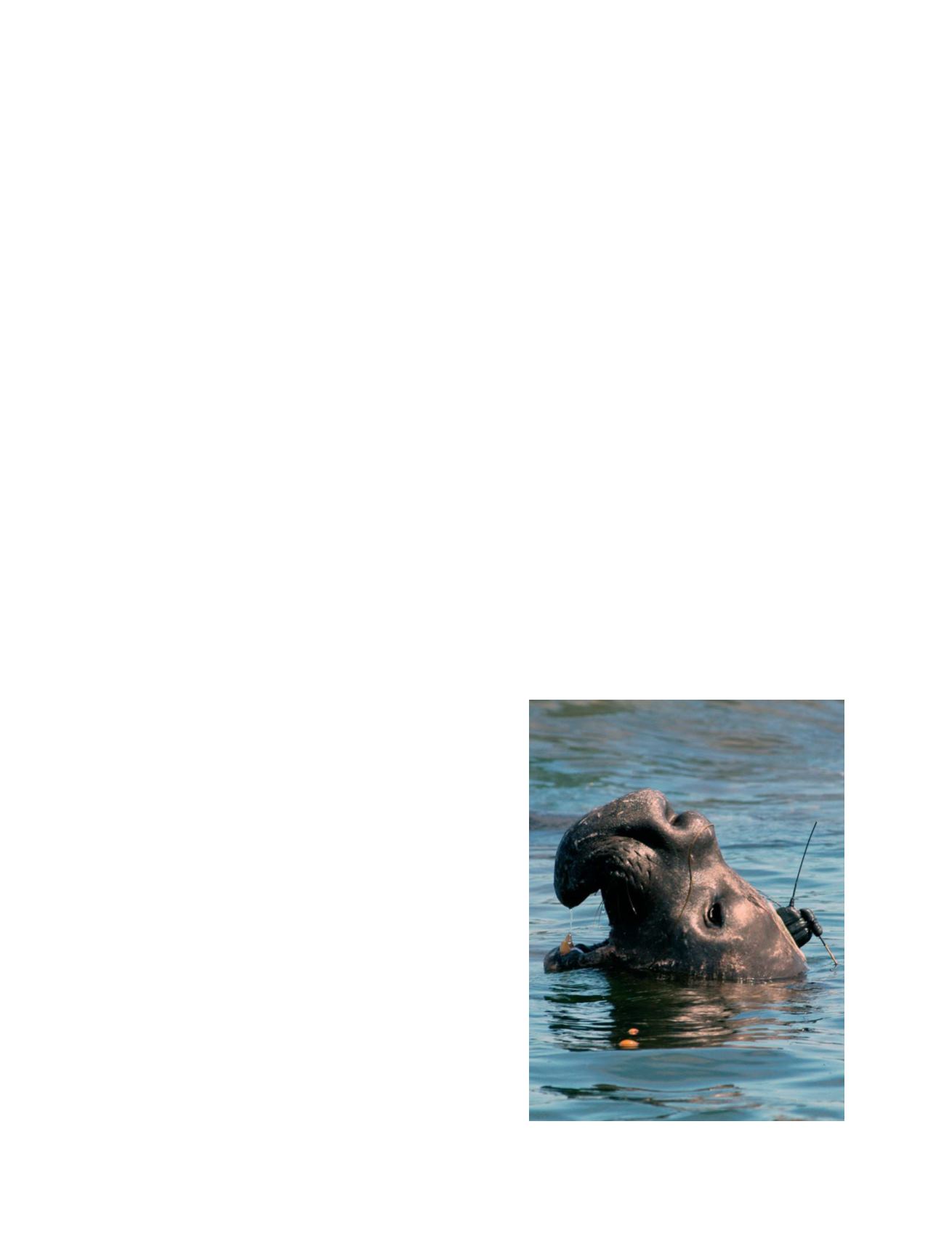

An elephant seal with a satellite tag attached

Photo: Dan Costa, University of California, Santa Cruz

S

OCIETAL

B

ENEFIT

A

REAS

– B

IODIVERSITY