[

] 33

Ethical

: “how should this relate to that?”, “what is wise

action?”, “how can we work towards the inclusive

well-being of the whole system – social, economic and

ecological?”

Practical

: “how do we take this forward with sustain-

ability in mind as our guiding principle?”

Such learning will ideally be reflexive, experiential, inquir-

ing, experimental, participative, iterative, real-world and

action-oriented. The sustainability learner will be char-

acterized by such qualities as resilience, resourcefulness,

creativity, systemic and critical thinking, enterprise, coop-

eration and care. What is required is ‘learning as change’

in the active pursuit of sustainability and in the design,

development and maintenance of ecologically sustainable

economic and social systems through changed lifestyles

and innovation. Such engaged learning goes beyond mere

‘learning about change’ or preparative ‘learning for change’

whichmay be seen as rather more passive steps on the way

to a deeper learning response.

This may sound far from the realities of everyday

educational practice, but experience in the UK, for

example, shows a rapid increase in interest and activity

around sustainability education and learning in recent

years. Thus, while there is still a long way to go in the

higher education sector, many universities – spurred

on by funding council policies (not least relating to

carbon management) and increasing demand from

an engaged student body – are recognizing sustain-

ability as an imperative that needs a whole-institution

response. This has been supported strongly by such

organizations as the Higher Education Academy

6

and the Environmental Association for Universities

and Colleges,

7

which play an important facilitative

role in developing and energizing networks of key

institutions and individuals, undertaking research

and spreading good practice. At the the same time,

lead institutions are pushing the pace of change for

the sector as a whole. This includes the University of

Plymouth, where the whole-institution programme

working on Campus, Curriculum, Community and

Culture over the last five years now sees sustainability

linked strongly to enterprise as the touchstones of the

university’s identity and work.

8

Last chance to make a difference

The UK Future Leaders Survey 2007/08, which inter-

viewed some 25,000 young people in the UK, makes

it clear that they are “intensely aware of the big chal-

lenges facing the planet”, but also notes that they are

the last generation with a chance to put things on

a more sustainable course. Given this critical chal-

lenge, learning for sustainable development now

needs to be absolutely central to educational policy

and practice and enmeshed with all other agendas.

As a recent UK report on education for sustainable

development in the UK shows,

9

at this point, we can

be cautiously optimistic – but the unsustainability

clock is still ticking.

and learning over recent years. Yet there is potential for confusion

amongst those coming to it for the first time, given all the lists of key

concepts, values and skills that various writers and bodies suggest

are essential in learning for sustainable development.

5

I would suggest that the newly interested policymaker or prac-

titioner look for commonality between the various frameworks,

regarding them as indicative rather than prescriptive. They are there

to be used, edited, critically discussed and adapted as part of the

learning process, rather than adopted wholesale.

Whilst lists of sustainability-related concepts, skills and values are

beneficial, at a more fundamental level, it is the change of perspec-

tive and learning culture which is key in order to move us away from

the perspectives and culture that have supported unsustainability.

In terms of educational practices, it means that curriculum design-

ers and teachers develop learning situations where the potential for

transformative learning experiences, both for themselves and their

students, is made more likely. In essence, this shift can be expressed

in terms of eight key questions that can help unlock thinking when

considering any issue:

Holistic

: “how does this relate to that?”, “what is the larger context here?”

Critical

: “why are things this way, in whose interests?”

Appreciative

: “what’s good, and what already works well here?”

Inclusive

: “who/what is being heard, listened to and engaged?”

Systemic

: “what are or might be the consequences of this?”

Creative

: “what innovation might be required?”

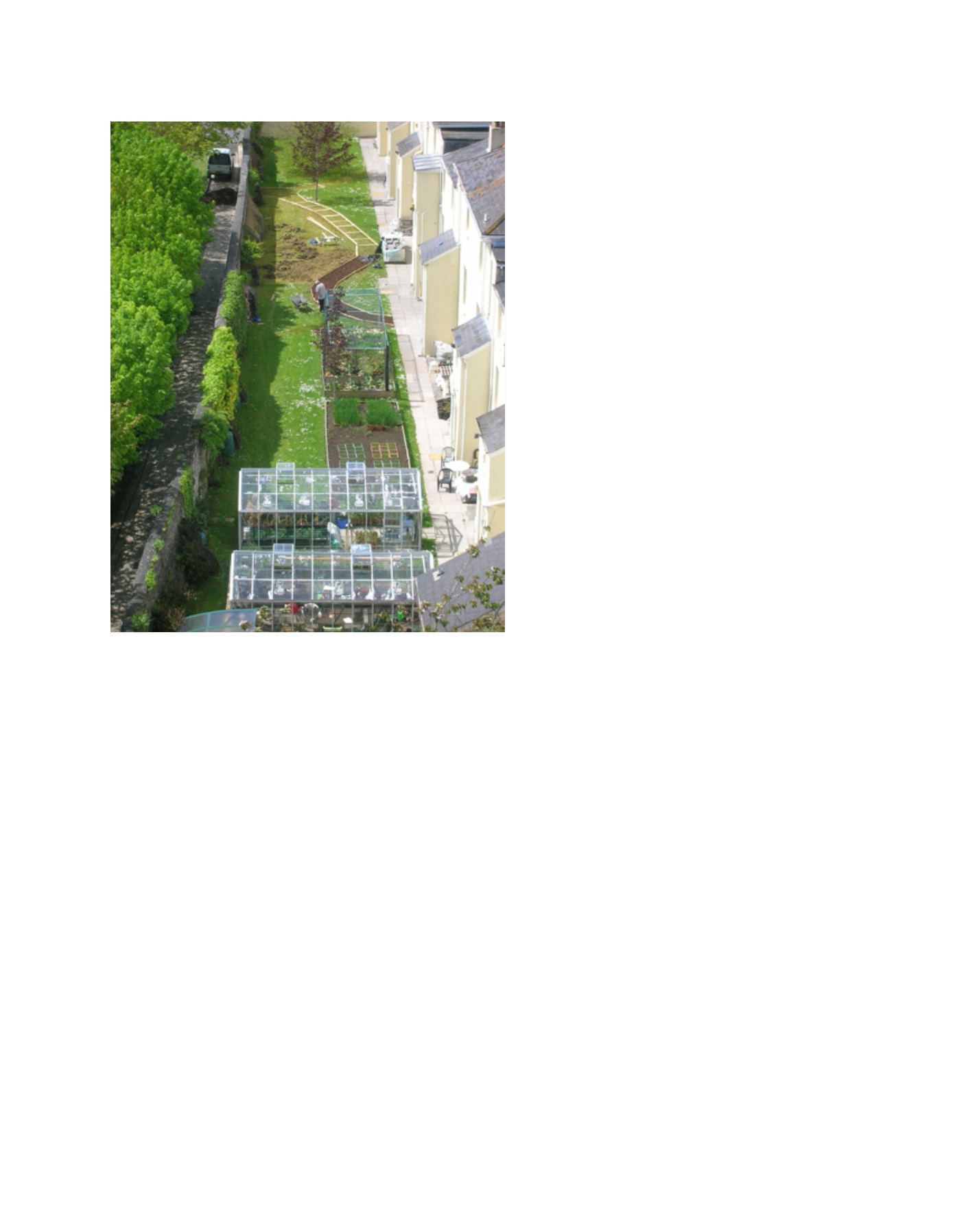

Gardens at the University of Plymouth are being opened for environmental teaching

Image: University of Plymouth